YALE LAW LIBRARY SERIES IN LEGAL HISTORY AND REFERENCE

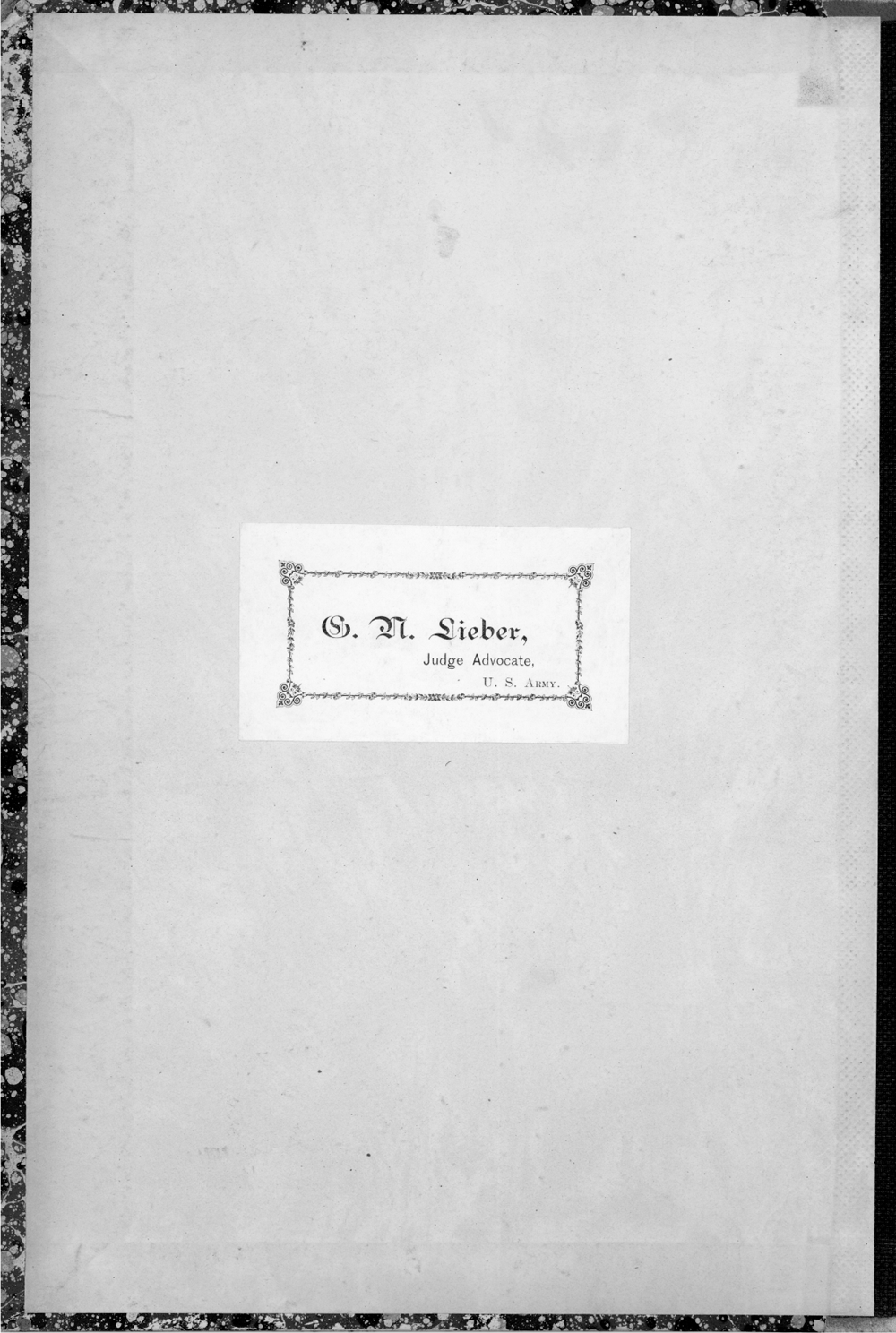

Figure 1. Norman Liebers bookplate, affixed to the inside cover of the notebook containing the manuscript. Source: National Archives.

To Save the Country

A Lost Treatise on Martial Law

FRANCIS LIEBER AND G. NORMAN LIEBER

Edited and with an Introduction

by Will Smiley and John Fabian Witt

Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven and London

Published with support from the Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School.

Copyright 2019 by Will Smiley and John Fabian Witt.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Minion type by Newgen North America, Austin, Texas.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018966490

ISBN 978-0-300-22254-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedicated to the judge advocates of the United States armed forces and to the civil liberties lawyers who engage thembringing law to force for a century and a half.

Contents

Acknowledgments

This project began when one of us stumbled across a nearly unreadable and badly jumbled nineteenth-century manuscript hidden deep in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Making the manuscript legible and decoding its many lost references has involved more than simply the work of the two editors. For more than a century, archivists and record-keepers in the United States Army and later at the National Archives and Records Administration cared for the manuscript. Little on the surface of it revealed its value, but the professionalism and commitment of these officials in the federal government preserved the manuscript nonetheless. The attention of these civil servants made our work possible. We are deeply grateful, too, for the excellent assistance of the archivists at the National Archives where we spent painstaking days and weeks photographing the manuscript.

The Yale Law Library performed with its accustomed brilliance, too, helping us locate difficult-to-find texts. Master librarians Julian Aiken, Lora Johns, John Nann, and Fred Shapiro were especially helpful, as were Teresa Miguel-Stearns and Blair Kauffman as heads of the library. The Hauser Library at Reed College was also helpful, particularly in researching the chapter annotations.

A small army of graduate and law students served as research assistants and made it possible for us to bring the project to completion. Arjun Ramamurti threw himself into the work of researching dozens of annotations. Samuel Breidbart, Michael Cotter, Berit Fitzsimmons, Chris Haugh, Tobias Kuehne, Jorge Bonilla Lopez, David G. Miller, Lauren Miller, Rob Nelson, Gabe Perlman, Todd Spencer, and Brandon Thompson provided indispensable assistance on the project: tracking down obscure references, scrutinizing the text, and translating the Latin and German passages that displayed the Liebers scholarly erudition.

David Dyzenhaus, Gary Gerstle, Joel Isaac, Duncan Kelly, and Nomi Lazar offered invaluable comments at a States of Exception in American History conference at Clare College, Cambridge, in 2015. Heroically, members the same group offered still more reactions and ideas at a follow-up conference at the University of Chicago in 2018. The project began when both authors were at Yale, where Bruce Ackerman, Scott Shapiro, and student members of the reading group in the Yale branch of the American Constitution Society offered constructive feedback on the Lieber manuscript and our interpretation of it. Bernadette Meyler generously read the manuscript and suggested a brilliant addition. A workshop at the University of Southern California Law School led by Daria Roithmayr and Ariela Gross helped refine our thinking. The manuscript also benefited from an audience at the Lieber Institute of the United States Military Academy at West Point in October 2018, where Laurie Blank, Rich Gross, Jens Ohlin, Shane Reeves, Richard Salomon, Mike Schmidt, and others weighed in with a number of helpful suggestions. We are also grateful to Bill Frucht and Karen Olson of Yale University Press, and to the Presss two anonymous reviewers.

Editors Note on the Text

This book consists of a lost manuscript by nineteenth-century political theorist and jurist Francis Lieber and his son G. Norman Lieber along with an introduction and editorial annotations. We found the Liebers manuscripts on martial law and emergency constitutionalism in the U.S. National Archives and Record Administrations Judge Advocate General files, among the personal papers of Norman Lieber. The manuscripts consist of two closely connected parts. The first (hereinafter GNL MS) is a manuscript that appears mostly to be in Norman Liebers own hand. Longer excerpts from other sources appear to have been written by another person (perhaps an assistant or secretary). Based on references internal to the text, much or most of it was written or edited sometime after 1874.

The second manuscript is the beginnings of an annotated edition of General Orders No. 100 (hereinafter FL MS). Several paragraphs, cut from the printed order, are pasted separately on pages of stationery. Notes are attached, in what appears to be Francis Liebers hand. Norman Lieber printed passages from these notes in two articles published during his own lifetime, referring to them as a manuscript note written by Francis Lieber and found among his papers after his These notes were almost certainly written between 1863, when Francis Lieber wrote General Orders No. 100, and 1872, when he died.

Preparing the texts of the GNL MS and the FL MS posed several challenges. For one, the manuscripts were in considerable disorder. They appear to have been relatively early drafts, with a number of different kinds of errors and much awkwardness. Errors include typographical errors, mistakes of citation, and omissions or inadvertent alterations in the Liebers long quotations from other texts.

We have tried to act as fiduciaries for the reader, editing the text to make it readable while neither altering the Liebers meaning nor sparing the Liebers from those mistakes or practices that bear on the significance of the text. Accordingly, we have fixed without comment minor typographical errors and obviously inadvertent errors. We have usually done the same with the Liebers informal citations to earlier texts. Our practice with such citations has been to replace the informal manuscript citations with formal citations complete with editorial information to help the interested reader identify and pursue the text to which the Liebers meant to refer. We have done our best to locate the particular editions on which the Liebers most likely relied, though in some cases this involved some guesswork. We have also added citations where the Liebers draft manuscript omitted them. Such citations appear in numbered footnotes interspersed among the Liebers own citations and footnotes.

Most importantly, we have added to the manuscript a series of our own editorial annotations, usually offering short explanations for references in the text that might be obscure to the modern reader. The Liebers range widely over Anglo-American constitutional history in their account of the emergency power, and we aim to allow the reader who encounters an unfamiliar reference to understand the significance of the person or event under discussion.

Next page