Three nationwide radio networks broadcasted this song, dedicated to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Cover of sheet music. Courtesy of the National Park Service.

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2009 by Connie M. Huddleston

All rights reserved

All photographs are courtesy of the National Archives unless otherwise noted.

First published 2009

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.283.1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Huddleston, Connie M.

Kentuckys Civilian Conservation Corps / Connie Huddleston.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-729-6 (alk. paper)

1. Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) 2. Forests and forestry--Kentucky--History--20th century. 3. Parks--Kentucky--History--20th century. I. Title.

SD144.K4H83 2009

333.761509769--dc22

2009030603

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

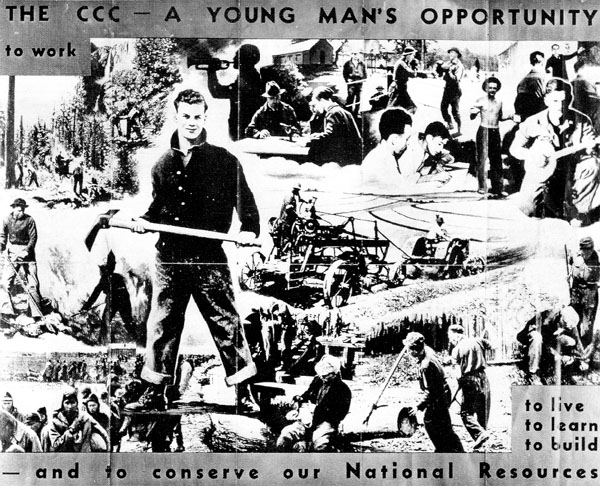

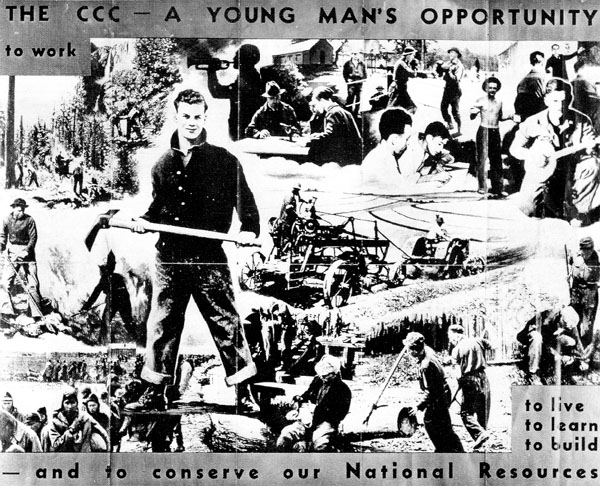

Across the nation, recruiting posters for the CCC enticed young men to join the corps. Most enrollees tell of hearing about the CCC from other local enrollees.

Contents

Acknowledgements

My fascination with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) started with a series of exhibits I planned for Georgia State Parks. It grew with the discovery of hundreds of CCC photographs at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. Later, the stories of these boys and young men who created so many of our national and state parks captured my complete attention and enticed me to write about the CCC for the people of Georgia, where I currently live, and Kentucky, which will always be my home. This book is dedicated to those CCC boys whose faces look out from these historic photographs, telling us of a time when a president promised a New Deal for all Americans and made good on his promise to many young men by creating the CCC.

Books may be authored by one individual, but they always seem to be a group effort. My support group deserves and receives my sincere thanks. First, I thank Charlie, my husband, for encouraging my efforts in all that I do. He is also valued as an editor. Second, I thank my mother, Carol Aldridge, whose unwavering love and support has always been there. Next, I thank two friends who served as personal editors. First is Sherron Lawson, without whom I cannot imagine my world. She is a great editor but an even better friend. Finally, there is Gwen Koehler, daughter of a CCC man, who has given me some of her precious time and talents to edit both of my books on the CCC.

I also give my special thanks to Lori and J.O. Powers for sharing the story and photographs of Fred Powers, one of Kentuckys CCC men. This effort would not have been possible without the great stories passed down by Kentuckys CCC boys.

My editor, John Wilkinson, made this project easier than I expected by giving me lots of advice and quickly answering my many questions. I appreciate his efforts on my behalf to see this book published by The History Press.

Introduction

It has frequently been said that someone, or some group, made a significant contribution to his fellow man, the environment or society as a whole. Journalists and historians have often applied this same catchphrase to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the most popular of President Franklin D. Roosevelts New Deal programs implemented to relieve the substantial burdens placed on every American during the Great Depression. The CCC planted trees; provided soil conservation measures; built trails, firebreaks, fire towers, bridges and state and national parks; and supplied labor for other necessary jobs, all while leaving a legacy of far-reaching impact on the American landscape. Yet few Americans today realize that the most significant role played by the CCC was the employment, education and enrichment FDRs forest army provided to a lost generation of young men.

In the summer of 1932, the Democratic Party nominated Franklin D. Roosevelt, then governor of New York, for president. In his acceptance speech, Roosevelt focused on the problems created by the Great Depression, telling the American people, I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people. FDR took the oath of office on March 4, 1933, and faced a nation in which soup lines fed many of the 12 to 15 million unemployed. Eleven thousand of the United States twenty-five thousand banks had failed, robbing millions of Americans of their uninsured savings. Since Black TuesdayOctober 29, 1929trade had plummeted, construction had halted and the mining and logging industries had collapsed. Manufacturing had fallen to only 54 percent of its early 1929 level. Across the southern plains, the Great Dust Bowl had emerged, turning to dust farmlands devastated by poor agricultural practices and years of sustained drought. Crops failed, the sky darkened with blowing dust and even more Americans suffered the reality of the Great Depression. One in four young men between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four found himself unemployed, undereducated and living in poverty. Many took to the roads and rails, moving from town to town in search of food and work. They became known as the teenage tramps of America.

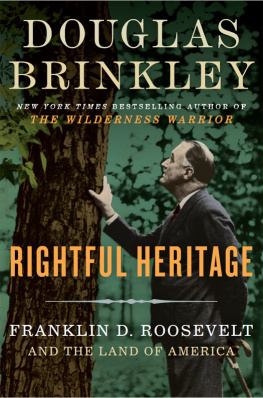

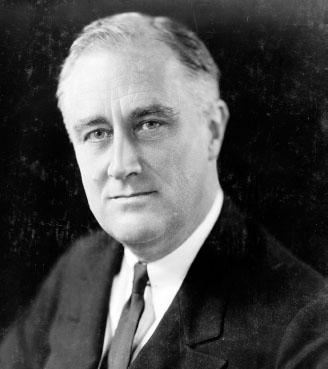

Many saw Franklin Delano Roosevelts love of nature and the outdoor life as a contributing factor to his establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Only five days into his administration, Roosevelt presented his plan to employ Americas young, unmarried men, ages eighteen to twenty-five, in conservation programs across the states. On March 9, 1933, he outlined the programs basic concepts to his secretaries of agriculture, the interior and war, the director of the budget, the armys judge advocate-general and the solicitor of the Department of the Interior. He demanded immediate action, asking Colonel Kyle Rucker, the armys judge advocate-general, and Edward Finney, the interior solicitor, to prepare a draft bill by that evening. It was completed and presented to the president at 9:00 p.m.

They proposed hiring 500,000 young men a year to be employed in conservation and public work projects. In an ambitious plan, FDR wanted 250,000 young men employed by early summer. The plan called for several agencies to play roles in the programs development. The army would recruit the enrollees and organize the camps. The Departments of Agriculture and the Interior would create and run the work programs.

In his third press conference, on March 15, 1933, FDR expounded on his ideas about creating work in Americas forests, the number of men that could be employed and the proposed wage of one dollar per day. Initially, there was opposition from organized labor to the low wage to be paid (average wage at that time was eighteen dollars per week for men) and from the public about the armys role in the program. In support of the program, which organized labor said would create open air sweat shops, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins emphasized the administrations view of this new program as a relief measure directed at one segment of society: young, unmarried men who would be provided with food, shelter and clothing, along with medical and dental care. These young men would be volunteers, not drafted. Ms. Perkins defended the armys role as necessary to create the organization and infrastructure needed by the corps.

Next page