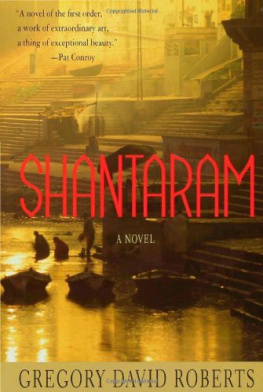

SHANTARAM

SHANTARAM

Gregory David Roberts

St. Martins Press  New York

New York

SHANTARAM . Copyright 2003 by Gregory David Roberts. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martins Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY. 10010.

www.stmartins.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roberts, Gregory David.

Shantaram : a novel / Gregory David Roberts.1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-312-33052-9

EAN 978-0312-33052-1

1. AustraliansForeign countriesFiction. 2. Fugitives from justiceFiction. 3. AustraliansIndiaFiction. 4. Bombay (India)Fiction. 5. CriminalsFiction. 6. ClinicsFiction. I. Title.

PR9619.4.R625S53 2004

First published in Australia and New Zealand by Scribe Publications

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

CONTENTS

For my mother

I T TOOK ME a long time and most of the world to learn what I know about love and fate and the choices we make, but the heart of it came to me in an instant, while I was chained to a wall and being tortured. I realised, somehow, through the screaming in my mind, that even in that shackled, bloody helplessness, I was still free: free to hate the men who were torturing me, or to forgive them. It doesnt sound like much, I know. But in the flinch and bite of the chain, when its all youve got, that freedom is a universe of possibility. And the choice you make, between hating and forgiving, can become the story of your life.

In my case, its a long story, and a crowded one. I was a revolutionary who lost his ideals in heroin, a philosopher who lost his integrity in crime, and a poet who lost his soul in a maximum-security prison. When I escaped from that prison, over the front wall, between two gun-towers, I became my countrys most wanted man. Luck ran with me and flew with me across the world to India, where I joined the Bombay mafia. I worked as a gunrunner, a smuggler, and a counterfeiter. I was chained on three continents, beaten, stabbed, and starved. I went to war. I ran into the enemy guns. And I survived, while other men around me died. They were better men than I am, most of them: better men whose lives were crunched up in mistakes, and thrown away by the wrong second of someone elses hate, or love, or indifference. And I buried them, too many of those men, and grieved their stories and their lives into my own.

But my story doesnt begin with them, or with the mafia: it goes back to that first day in Bombay. Fate put me in the game there. Luck dealt the cards that led me to Karla Saaranen. And I started to play it out, that hand, from the first moment I looked into her green eyes. So it begins, this story, like everything elsewith a woman, and a city, and a little bit of luck.

The first thing I noticed about Bombay, on that first day, was the smell of the different air. I could smell it before I saw or heard anything of India, even as I walked along the umbilical corridor that connected the plane to the airport. I was excited and delighted by it, in that first Bombay minute, escaped from prison and new to the wide world, but I didnt and couldnt recognise it. I know now that its the sweet, sweating smell of hope, which is the opposite of hate; and its the sour, stifled smell of greed, which is the opposite of love. Its the smell of gods, demons, empires, and civilisations in resurrection and decay. Its the blue skin-smell of the sea, no matter where you are in the Island City, and the blood-metal smell of machines. It smells of the stir and sleep and waste of sixty million animals, more than half of them humans and rats. It smells of heartbreak, and the struggle to live, and of the crucial failures and loves that produce our courage. It smells of ten thousand restaurants, five thousand temples, shrines, churches, and mosques, and of a hundred bazaars devoted exclusively to perfumes, spices, incense, and freshly cut flowers. Karla once called it the worst good smell in the world, and she was right, of course, in that way she had of being right about things. But whenever I return to Bombay, now, its my first sense of the citythat smell, above all thingsthat welcomes me and tells me Ive come home.

The next thing I noticed was the heat. I stood in airport queues, not five minutes from the conditioned air of the plane, and my clothes clung to sudden sweat. My heart thumped under the command of the new climate. Each breath was an angry little victory. I came to know that it never stops, the jungle sweat, because the heat that makes it, night and day, is a wet heat. The choking humidity makes amphibians of us all, in Bombay, breathing water in air; you learn to live with it, and you learn to like it, or you leave.

Then there were the people. Assamese, Jats, and Punjabis; people from Rajasthan, Bengal, and Tamil Nadu; from Pushkar, Cochin, and Konarak; warrior caste, Brahmin, and untouchable; Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Buddhist, Parsee, Jain, Animist; fair skin and dark, green eyes and golden brown and black; every different face and form of that extravagant variety, that incomparable beauty, India.

All the Bombay millions, and then one more. The two best friends of the smuggler are the mule and the camel. Mules carry contraband across a border control for a smuggler. Camels are unsuspecting tourists who help the smuggler to get across the border. To camouflage themselves, when using false passports and identification papers, smugglers insinuate themselves into the company of fellow travellerscamels, wholl carry them safely and unobtrusively through airport or border controls without realising it.

I didnt know all that then. I learned the smuggling arts much later, years later. On that first trip to India I was just working on instinct, and the only commodity I was smuggling was my self, my fragile and hunted freedom. I was using a false New Zealand passport, with my photograph substituted in it for the original. Id done the work myself, and it wasnt a perfect job. I was sure it would pass a routine examination, but I knew that if suspicions were aroused, and someone checked with the New Zealand High Commission, it would be exposed as a forgery fairly quickly. On the journey to India from Auckland, Id roamed the plane in search of the right group of New Zealanders. I found a small party of students who were making their second trip to the sub-continent. Urging them to share their experience and travellers tips with me, I fostered a slender acquaintance with them that brought us to the airport controls together. The various Indian officials assumed that I was travelling with that relaxed and guileless group, and gave me no more than a cursory check.

I pushed through alone to the slap and sting of sunlight outside the airport, intoxicated with the exhilaration of escape: another wall scaled, another border crossed, another day and night to run and hide. Id escaped from prison almost two years before, but the fact of the fugitive life is that you have to keep on escaping, every day and every night. And while not completely free, never completely free, there was hope and fearful excitement in the new: a new passport, a new country, and new lines of excited dread on my young face, under the grey eyes. I stood there on the trample street, beneath the baked blue bowl of Bombay sky, and my heart was as clean and hungry for promises as a monsoon morning in the gardens of Malabar.

Next page

New York

New York