PALMETTO JOURNAL

ALSO BY PHILLIP MANNING

Afoot in the South: Walks in the Natural Areas of North Carolina

Copyright 1995 by Phillip Manning

Printed in the United States of America

All Rights Reserved

DESIGN BY DEBRA LONG HAMPTON

MAPS AND COMPOSITION BY LIZA LANGRALL

ILLUSTRATIONS BY DIANE MANNING

PRINTED AND BOUND BY R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS

The paper in this book meets the

guidelines for permanence and

durability of the Committee on

Production Guidelines for Book Longevity

of the Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Manning, Phillip, 1936

Palmetto journal : walks in the natural areas of South Carolina / Phillip Manning.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-89587-124-6

1. Natural historySouth CarolinaGuidebooks. 2. Natural areasSouth CarolinaGuidebooks. 3. WalkingSouth CarolinaGuide-books. 4. HikingSouth CarolinaGuidebooks. 5. South CarolinaGuidebooks. I. Title.

QH105.S6M36 1995

508.757dc20 9449584

For

Eileen Benson Manning Elliott

(1914-1986)

who taught me about the stateand more.

It is inconceivable to me that

we can adjust ourselves to the

complexities of the land mechanism

without an intense curiosity to

understand its workings and an

habitual personal study of those

workings. The urge to comprehend

must precede the urge to reform.

Aldo Leopold, Round River

Biophilia is a new theory proposed by E.O. Wilson of Harvard University, one of the worlds top evolutionary biologists. It posits that we humans are genetically attracted to natural areas because of how and where our species evolved. The theory has not been thoroughly investigated and is, perhaps, unprovable. But I think the idea has merit, and it certainly offers a handy rationale for a choice I made.

Yes, dear, I have quit my job so I can spend more time in the woods. Its a genetic thing. We call it biophilia.

Walking in natural areas is a great delight for me. Diane, my wife and the illustrator of this book, loves the outdoors, too. We have been wandering through parks and forests and wildlife refuges for years, and she went along on most of the walks in this book. Because I grew up in South Carolina and worked there as a young man, my file folders bulge with material that I picked up twenty-five or more years ago, when I first walked many of these trails. On my desk, for example, is a 1968 brochure from Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge; a 1976 advertisement for a trout fishing seminar at Oconee State Park; some notes about a canoe trip in Congaree swamp, long before it became Congaree Swamp National Monument; and so forth. But no matter how many times I have been to a place, a new visit always teaches me something I didnt know. Natural areas are complicated, ever-changing places. They remind me of the old joke about Columbia (and a lot of other cities): it will be a nice townif they ever finish it.

Like towns, natural areas are never finished. The landscape at Francis Marion National Forest barely resembles the one that existed there six years ago before Hurricane Hugo. And the pre-Hugo forest of the twentieth century was different from the one that covered that land in Francis Marions time. The longleaf pine and wire grass that the Swamp Fox knew were cleared by settlers, and loblolly pines and oaks marched across the land after it was abandoned. These, in turn, were mostly destroyed by the storm and are now being replaced by longleaf pines.

Despite superficial changes, though, I believe the land has a soul, an irreducible essence, and that a part of every natural landscape is timeless, or nearly so. Over 250 years ago, John Lawson, an early surveyor and explorer of the Carolinas, described a Piedmont forest that closely resembles one that stands today in the Long Cane Scenic Area of Sumter National Forestin spite of logging and abuse. Even in Hugo-altered Francis Marion National Forest, wisps of pre-European flora and fauna persist. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney would likely recognize Pinckney Island today, even though the cotton fields he planted there after the Revolutionary War have long since vanished. It is, in fact, this mixture of Constance and change, the way cultural and natural history mingle to shape the land, that makes the natural areas of South Carolina so intriguing and so worth a visit.

When I go to a natural area, I ask myself two questions: what is the land like, and how did it get that way? The rest of the day or weekend or week is spent searching for answers. That means I have to look around. And, for me, the only satisfactory way to look aroundto really see a placeis to walk the trails, to get out into the woods or on the beach or in the marsh. After the field work is complete, I talk to anybody that knows something about the place and read everything I can get my hands on. Even so, I know my answers are incomplete, that theres always more to learn, so I also try to just enjoy myself. This, it turns out, is probably the best reason to visit South Carolinas natural areas: to see its marshes and old rice fields, its rolling hills and surprisingly rugged mountains; to watch perky Carolina wrens and elegant swallow-tailed kites; to spy on alligators and beavers, bald-faced hornets and red-spotted newts. And if all that is not enough of a reason, if you need to further explain your hunger to go into natural areaseither to yourself or to someone elseyou might want to trot out biophilia. Its only a theory, but its a useful theory.

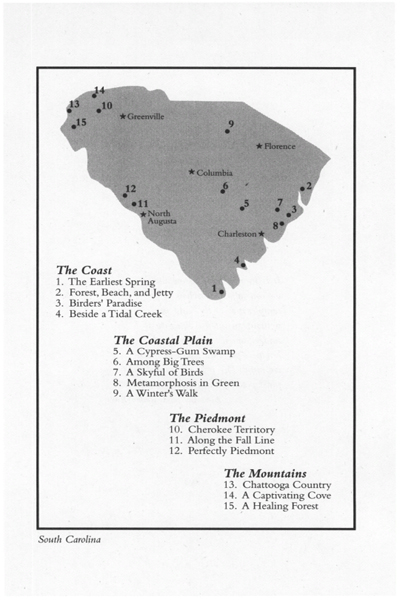

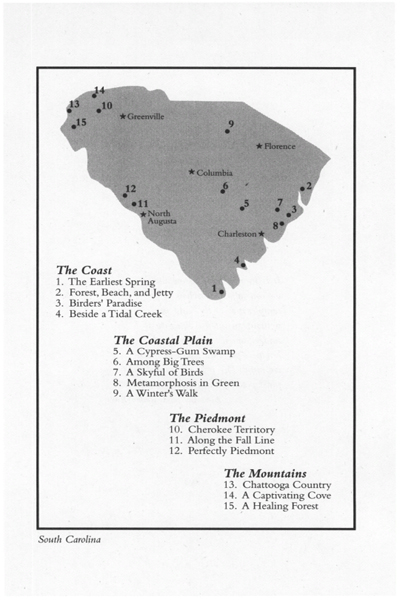

South Carolina is a naturalists delight. It rises from sea level along the Atlantic coast to 3,554 feet at its highest point, Sassafras Mountain, a peak in the Appalachian range. According to a South Carolina Wildlife and Marine Resources bulletin written by John B. Nelson, the state has sixty-seven different natural communities, ranging from Acidic Cliff to Xeric Sandhill Scrub. Much of this diversity arises from the states geography. South Carolina is divided into three physiographic provincesthe coastal plains, the Piedmont, and the mountains. Because this book is organized from a naturalists point of view, I have subdivided the coastal plains into two regions, treating the coast as a separate province. This is not geologically correct, but I believe the natural communities found at the coast differ enough from those of the inner coastal plains to justify separating them.

Within each of the four provinces, I have selected several walksnone of which requires backpackingto illustrate the natural habitats of that province. The windswept sprawl of marshes and impoundments at Santee Coastal Reserve is an example of one habitat of the coastal plains, while the beautiful hardwood coves near Caesars Head State Park are an example of a habitat found in the mountains.

Next page