First published 2015 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2015 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2014013018

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

On Folkways and mores : William Graham Sumner then and now / Philip Manning, editor.

pages cm. -- (Law and society)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4128-5300-2

1. Sumner, William Graham, 1840-1910. Folkways. 2. Manners and customs. 3. Sociology--United States. I. Manning, Philip.

GT75.S83O52 2015

390--dc23

2014013018

ISBN-13: 978-1-4128-5300-2 (pbk)

Philip Manning

Cleveland State University

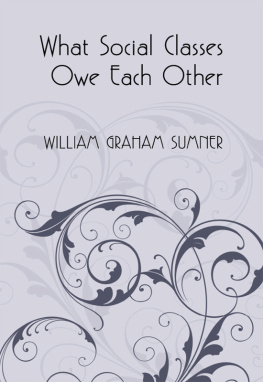

William Graham Sumner (18401910) published Folkways in 1906 in time to save himself from a fate to which he might not have objected too strongly. That is to say, had he not written this impressive volume in the twilight years of his career and life, Sumner would be remembered today solely as a combative, cantankerous, take-no-prisoners apologist for laissez-faire capitalism. Before Folkways, he was known as an advocate for big business, for deregulation or no regulation, for limited governmental oversight, and for the supposed Darwinian survival of the fittest. But Folkways established Sumner as a contributor to the sociological canon, a talented social thinker who gave us a rich vocabulary of conceptsfolkways, mores, ethnocentrismand as a precursor to symbolic interactionism. Folkways is a sociological classic, but Sumner himself was a divisive figure, and among American sociologists he might rank first in accumulated enemies.

But what really makes a classic? In an informative introduction to his study of the characteristics of social theory, Charles Turner (2010:19) identifies three criteria that are commonly employed in determining whether a book is a classic: authority, aesthetic power, and foundational ambition. Folkways likely meets all three. It is a benchmark for early American sociology, Sumners voice is heard in its sharp prose, and, in my view, it is a frequently overlooked precursor to symbolic interactionism (Manning, 2005). Turner reminds us that we usually say that we are rereading a classic rather than reading it, and yet every rereading is a new voyage of discovery (2010: 19). Inevitably, much of sociology can be very illuminating, once, but it frequently does not bear a second go-around. According to Turner (2010: 20), The CommunistManifesto or Durkheims Suicide or Webers Science as a Vocation are classics because of the sense of newness and surprise experienced even by a seasoned reader. This sense of newness is because these texts stay fresh and allow for repeated personal transformations as they are reread. This is indeed a high standard, but it is one that Folkways has the capacity to attain.

Reading and rereading any classic, and this classic in particular, is not easy. Before considering the hermeneutic challenges of examining the classics of a discipline, it is important to recognize the specific demands facing the different generations of readers of Folkways. For the first generation of American sociologists in the early twentieth century, Sumner was a political pariah, out of step with the Progressive politics favored by Albion W. Small, Robert E. Park, Charles Horton Cooley, George Herbert Mead, and other leading academics of the day. Worse, perhaps, Sumner was also a social pariah: he was an argumentative intellectual gunslinger, willing to ridicule the arguments of his adversaries. As Albert Galloway Keller states in the introduction to Folkways, when the Yale Commencement orator presented Sumner with a Doctorate of Laws in 1909, even he described Sumner as someone whose heart has mellowed (p. vi). This of course suggests that Sumner had been brazenly hardhearted. In his remembrance of Sumner, his colleague William Lyon Phelps also portrayed Sumner as someone who was routinely rude or harsh in meetings, although kind and considerate outside of them (p. xii).

Sumners Folkways was a classic in the making that was not likely to have many supporters in his own time. Herbert Blumer, in particular, played a role in sidelining Folkways by taking Sumner out of the canon of symbolic interactionism. What Blumer really thought about Sumner is not known, but since he chose not to mention him at all, it is hard to think of Sumner as a precursor to symbolic interactionism.

And then there are the general questions confronting any text that could be described as a classic. These questions lead us to wonder what specific personal transformations Folkways brings about. Is it is a classic because it teaches us about Sumners time? Is it a classic because it teaches us about our own time? Is Sumner, ironically like Marx, explaining a transition, allowing us to see how we became who we now are? And who constitutes this we? Is it the contemporary reader who is a sociologist or the informed citizen? Or are we to read Folkways for pleasure, for the examples and insights it provides? Is it a classic because it introduced a vocabulary that has become part and parcel of the contemporary lexicon of social science? Finally, does Folkways make for compelling reading because Sumner himself was such a compelling, if flawed, man? By different degrees, Folkways teaches us something and appeals to us, for all of these reasons.

It is clear that Sumners critics could not forgive him for his earlier one-dimensional economic writings from the 1880s. Unlike his confrontational, populist work on economic and political topics, Folkways offers a sociological framework and terminology that remains extremely valuable. Thus, it is useful to follow the lead of historian Robert C. Bannister and distinguish between two Sumners. Bannister has made this argument to show that Sumner should not be understood as merely, and only, a social Darwinist. He describes Sumner as follows:

A defender of property, he was not a business hireling but a spokesman of an older middle class threatened by a variety of developments in American life. Accepting relativism and naturalism, he never relinquished his faith in individualism and democracy. By the end of his life, there were in effect two Sumners: the one a defender of an orthodoxy that most of his own middle class had deserted for progressive reform, and the other a pioneering sociologist whose