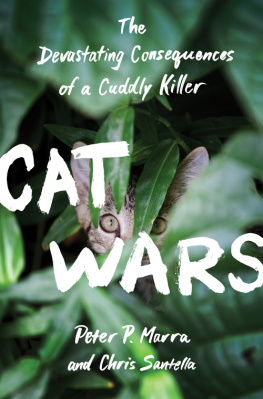

CAT

WARS

CAT

WARS

The Devastating Consequences

of a Cuddly Killer

PETER P. MARRA

AND CHRIS SANTELLA

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2016 by Peter P. Marra and Chris Santella

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket design and lettering by Amanda Weiss

Jacket image courtesy of iStock

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-16741-1

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my wife, Anne, for her encouragement, and thoughtful support, and to my kids, Aline and Gabe, may they have the opportunities to experience and understand the brilliance of the natural world. To my brother Michael, who loved all animals but left this world too soon.

P. M.

To my wife, Deidre, for her constant support and to my daughters, Cassidy and Annabel, that they might grow up to find a world still rich in biodiversity.

C. S.

CONTENTS

CAT

WARS

CHAPTER ONE

The Obituary of the

Stephens Island Wren

No matter how much the cats fight, there always seem to be plenty of kittens.

Abraham Lincoln

Rising high from the Marlborough Sound into the Maori sky off the South Island of New Zealand is Stephens Island. The island lies two miles from the mainland and fifty-five miles from Wellington, is no bigger than a quarter of a square mile, is taller than it is wide, and has peaks reaching almost 1,000 feet. Like all of the islands of the region, Stephens Island has short, craggy, and almost impenetrable vegetation, likely because the land is guilty of trying to stop the strong and persistent southeasterly winds sweeping in from the Antarctic Continent. According to historical accounts, landing on the island was so treacherous that few people had ever stepped foot on its shores, which left it largely pristine. In fact, the island had likely stood in place for millions of years without human impact; if the Maori people had ever visited, they left no trace. Anglo explorations of the island began in the 1870s, led by New Zealand maritime officials who had determined that a lighthouse installation was needed to ensure safe passage through nearby channels. Several hundred people had lost their lives in three major shipwrecks in the mid-1800s in New Zealand, so lighthouse construction had become a priority. By the early 1890s a lighthouse and several modest homes had been erected on Stephens Island for three lighthouse keepers and their families to share. With little human companionship, lighthouse keepers would often bring cats with them to their island outposts. As one story goes, a cat, possibly named Tibbles, made it to Stephens Island and was allowed to roam free.

David Lyall liked his solitude. He was literate, fit, and orderly, but, most important, he could keep a paraffin lantern burning cleanly. Lyall was cautiously excited about his new position as an assistant lighthouse keeper for New Zealand Maritime. It was January 1894, and he would be one of seventeen people at this new outpost. Being a lighthouse keeper in the late 1800s was not an easy job, although the primary dutykeeping the light burning bright and cleanwas straightforward, requiring a constant trimming of the wick to maximize the flame and reduce the smoke. Many lives were in the keepers hands: A rock near an island on a coal-black night could tear through the wooden belly of a ship in a matter of seconds, meaning an almost certain death for sailors. Many sailors at the time could not swim and, ironically, hated waterespecially the frigid subantarctic waters enveloping the southern islands of New Zealand.

The challenge of being a lighthouse keeper was one of enduranceenduring rough weather, the claustrophobically small community, the lack of fresh food, and most of all the isolation. Lighthouse keepers received new provisions from the mainland only twice a month. To bolster their larder, they might keep cows for fresh milk, sheep for wool, chickens for eggs. They might garden a bit if the soil and weather permitted. Lyall was not daunted by these challenges. He had a wife and at least one son, so he needed to make a fair wage. He was also eager to pursue his passions, even if doing so meant life on an isolated island. Lyall loved animals and had an insatiable curiosity for natural history and especially for watching birds. An amateur ornithologist, he was especially eager to study the avifauna of the island and envisioned perhaps even preparing some bird specimens for museums.

Lyall likely was preoccupied at an early age with a need for order, and this would have contributed to a need to name and classify everything he saw in nature. In his passion for animals and their nomenclature, Lyall probably found comfort and an explanation for how nature worked. It was like solving a puzzle, revealing something previously unknown, and providing order to a natural landscape that appeared to be in disorder. Lyall was a self-taught naturalist, drawing most of his understanding from the few books that were available on the natural history of New Zealand (field guides had yet to be invented). He may have found inner peace in nature, through watching birds and their behaviors, and identifying and ascribing names to existing species. Lyall also probably found an inherent value in nature that he could not quantify, justify, or even articulate. He was blindly focused on getting to his new post on the largely unexplored and uninhabited island, a place where he could finally pursue his passions. He envisioned spending long nights deep in thought, identifying specimens of plants, insects, and birds, burning through large amounts of paraffin oilall while supporting his family.

Lyall would find the perfect study species for his avian interests in the Stephens Island Wren, then undescribed but eventually to be named Xenicus (Traversia) lyalli. Except for feathers and eggs, the Stephens Island Wren bore more resemblance to a mouse than a bird. It lived a hobbit-like existence, foraging in logs and even in underground burrows and boulder piles. Some accounts even suggest the wren was semi-nocturnal. Equipped with large feet and a short tail, it ran low to the ground among the shoreline rocks or jumped from branch to branch through thick tangles of knotty shrubs. It flapped its vestigial wings to help on the occasional long jumpperhaps its closest approximation to flight. Nearly everything about this species made it wren-like, though it was not actually a member of the wren family (we will continue to refer to it as a wren), but instead was a member of the endemic New Zealand family Acanthisittidae. It was one of only three flightless species of songbirds in the world. It did not need to fly. There was no need to leave the island or the ground for longfood was available throughout the year, and the species could breed on the island. More important, there were no predators. Flying requires trade-offs with other costly adaptations, and because there was no need to escape or migrate, this small wren, weighing little more than a large coin, lost its ability to fly.

The Stephens Island Wren was millions of years in the making. Enormous evolutionary changes in natural history and biology had occurred over time, generation after generation, to make it unique. Each year wrens nested, laid eggs, raised youngsometimes more, sometimes less, depending on the quality of the mate, the amount of food available, the climate, or some complex mix of all these things. The species size, color, and shape changed at varying speeds over time, sometimes at a glacial pace, sometimes more rapidly. But this species, like all species of plants and animals, changed at a pace to fit the landscapethe biological, climatic, and geological landscapeall through the process of natural selection. A story told over and over again, all over the planet, for thousands, hundreds of thousands, even hundreds of millions of years. In contrast with the slow pace with which the process of speciation can proceed, the reverse process of species extinction can occur with astonishing speed.

Next page