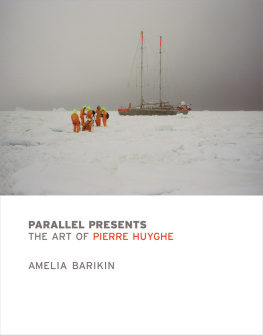

Parallel Presents

Parallel Presents

The Art of Pierre Huyghe

Amelia Barikin

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2012 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barikin, Amelia, 1979

Parallel presents : the art of Pierre Huyghe / Amelia Barikin.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-01780-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-262-31533-3 (retail e-book)

1. Huyghe, Pierre, 1962Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Title: Art of Pierre Huyghe.

N6853.H88B37 2012

700.92dc23

2011052778

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r1

For Vickie Douglas

August 4, 1951March 7, 2011

Acknowledgments

This book has greatly benefited from the assistance of numerous institutions and individuals. I am grateful to all the friends, family, and colleagues who contributed their time, feedback, love, knowledge, support, and editorial skills. Special thanks go to Albert Mishriki; Vickie, Robert, and Scott Douglas; Drew Roberts; Helen Metzger; Karla Pringle; Ben Bourke; Jesslyn Moss; James Jamison; Huw Hallam; Tim Webster; Joe Talia; Ryan Johnston; and most especially to Angela Woods and Anthony Gardner, whose remarkable critical insights have significantly shaped my thoughts.

This book commenced as a doctoral thesis at the University of Melbourne, Australia, under the supervision of Charles Green, whose work continues to inspire my own. I would like to thank my associate supervisor Anthony White for his comments on earlier drafts, as well as my colleagues Nikos Papastergiadis and Scott McQuire at the School of Culture and Communication for their support and wisdom. George Bakers and Felicity Scotts critical feedback on the original incarnation of the manuscript also proved immensely valuable in preparing this book for publication, and I thank them both for their comments.

Research was conducted at Dia Art Foundation, New York; the Public Art Fund, New York; Portikus gallery, Frankfurt (special thanks to Jochen Volz); Ca-stello di Rivoli Museo dArte Contemporanea; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; the Muse dArt Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris and New York; and the former Galerie Roger Pailhas in Marseille. Funding for research and writing was provided by an Australian Postgraduate Award, a Fieldwork Grant from the University of Melbourne Faculty of Arts, and a Norman Macgeorge Traveling Scholarship. Many thanks also are due to Roger Conover and the editorial team at the MIT Press for their marvelously smooth facilitation of the publication process, as well as to the French Embassy in New York which made possible the inclusion of color images in this book: an invaluable addition to the text for which I am hugely appreciative.

Numerous curators, gallery staff, and archive coordinators in Melbourne, Sydney, Paris, Amsterdam, Frankfurt, New York, Boston, and Oxford have provided research materials, advice, and contacts, and I would like to thank them for sharing their time and knowledge with me, including Jane Koh, Bettina Funcke, Sjouke van der Meulen, Sarah Thorn, Paul Andrejco and the crew at Puppet Heap, Astrid Bowron, Lysele Poulson, Matthew Barone, Katrina Pym, Jarrod Rawlins, and Judith Blackall. I am particularly indebted to Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Senior Curator of the Castello di Rivoli, whom I interviewed during Huyghes major retrospective exhibition at the Castello in 2004, and who generously facilitated my introduction to Pierre Huyghe. Many thanks also to the staff at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York and Paris for providing ongoing access to their archives and holdings, particularly Rose Lord, Agnes Fierobe, Catherine Belloy, Karina Daskalov, and Anas de Balincourt, and also to all of Huyghes past and present assistants including Mickal Pierson, Sophie Dufour, Ann Gale, and Ian Chengand most especially to Melissa Dubbin whose continued assistance has been invaluable.

This book draws extensively on numerous interviews and conversations I conducted with Huyghe in New York, Paris, and Sydney between 2005 and 2010. During the course of my research I have also been fortunate to speak with many of Huyghes friends, colleagues, and collaborators including Claude Closky, Matthieu Laurette, Maryse Alberti, Corinne Castel, Francesca Grassi, Renaud Sabari, Laurence Boss, Julia Garimorth, Emilie Renard, and Linda Norden. Without these conversations and encounters this book would not have been possible.

My warmest thanks go to Pierre Huyghe, whose generosity toward my research has been nothing less than extraordinary.

Introduction:

In What Time Do We Live?

A time negotiated in keeping with external constraints. A fiction extended into reality. An alternate coding of temporal practices. Over the past two decades, Pierre Huyghe has produced an extraordinary body of work that engages the time codes of contemporary society. An artist who has been described as an adventurer and an explorer, Huyghe has consistently worked with forms that do not fit into the frames in which they are made to appear. He has spoken repeatedly of the significance of deviant signs and fragile organisms: of the need for dynamic equivalences and blinking signals that cut across temporal partitions. More interested in processes of translation than the production of hermetic systems, Huyghes work strives to keep structures open to potential: to maintain ambiguity by manufacturing moments of elegant irresolution. The individuals ability to get a handle on the presentto experience duration, to resist the codification of time as producthas been a continued and ongoing concern of his practice.

The formats that Huyghe has turned to in investigating this possibility are rich and complex. Since leaving art school in Paris in the 1980s, he has researched the architecture of the incomplete, directed a puppet opera, founded a temporary school, established a pirate television station, staged celebrations, scripted scenarios, and journeyed to Antarctica in search of a mythical penguin. He has also made numerous films and screen-based works, and it was these that first established his reputation in the 1990s, to the extent that Huyghe has confessed that he spent a good part of that decade trying to persuade critics that he was not a video artist, while simultaneously fending off accusations as to his purported relational aesthetic. Huyghe is, however, definitively an ideas-based artist, and his projects can be situated among a lineage of conceptual and postconceptual practitioners that properly begins with Marcel Duchamp, traverses the praxes of artists such as Daniel Buren, Yves Klein, Marcel Broodthaers, Michael Asher, and Robert Smithson, and coalesces around the works of a younger group of artists who came into their own during the 1990s: artists such as Philippe Parreno, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Liam Gillick, and Maurizio Cattelan. Huyghe has collaborated with these and many other artists on numerous occasions, and indeed collaboration has always been a major part of his artistic process. Like Matthew Barney, his productions are now reliant on the skills of a vast network of specialist practitioners: gardeners, lighting operators, cinematographers, puppeteers, actors, architects, and composers.

It is in part because of Huyghes approach to media as a tool rather than a doctrine that critical reception of his practice has been so varied. His projects have been positioned against the backdrops of architecture, cinema, law, science, and art history. Curator Nicolas Bourriaud considered Huyghe an exemplar of his model of relational aesthetics in the 1990s; scientist Jean-Claude Amiesen has likened Huyghes open structures to the flux of subatomic particles. Writers Jean-Charles Massera and Jean-Christophe Royoux both described Huyghes works as mechanisms for reclaiming time, as it is lived, for the individual. This perspective is shared by curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargievs suggestion that Huyghes projects affirm the agency of the individual by working through the infinite interpretations and folds of reality that are possible at every moment.

Next page