Contents

List of figures

Guide

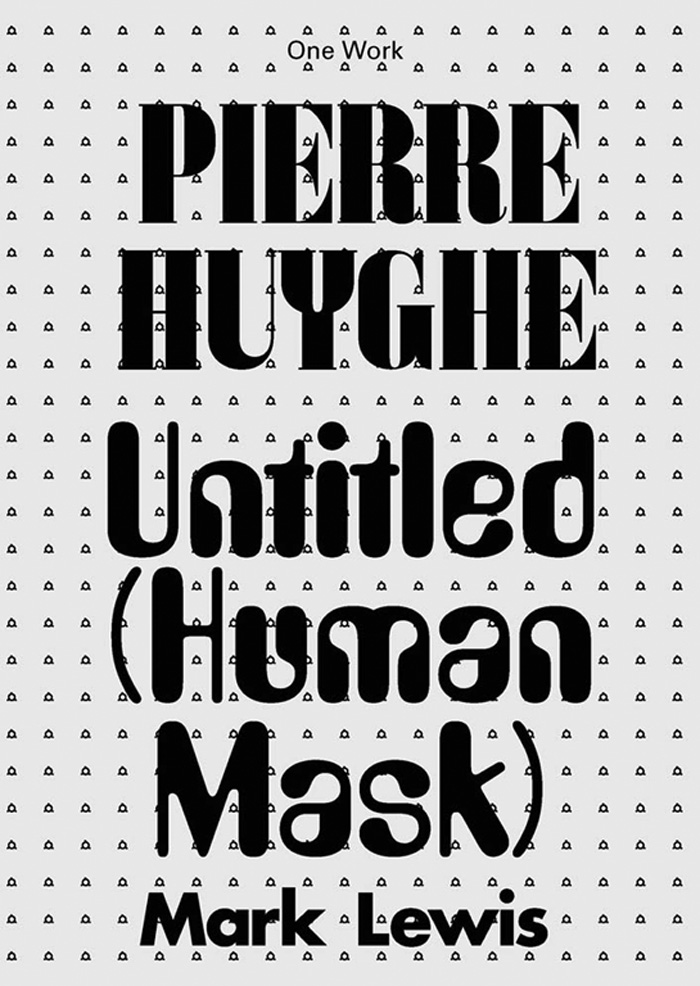

First published in 2021

by Afterall Books

Afterall

Central Saint Martins

University of the Arts London

Granary Building

1 Granary Square

London N1C 4AA

www.afterall.org

Afterall is a Research Centre of

University of the Arts London

Editors

Amber Husain

Mark Lewis

Copy Editor

Deirdre ODwyer

Project Coordinator

Camille Crichlow

Project Manager

Chloe Ting

Director

Mark Lewis

Associate Director

Charles Esche

Design

Andrew Brash

Typefaces for interior

A2/SW/HK + A2-Type

The One Work series is printed on FSC-certified papers

ISBN 978-1-84638-213-0

Distributed by the MIT Press,

Cambridge, Massachusetts and London

www.mitpress.mit.edu

2021 Afterall, Central Saint Martins,

University of the Arts London,

the artists and the authors

An Afterall Book

Distributed by The MIT Press

d_r0

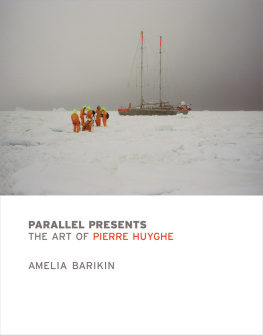

Each book in the One Work series presents a single work of art considered in detail by a single author. The focus of the series is on contemporary art and its aim is to provoke debate about significant moments in art's recent development.

Over the course of more than one hundred books, important works will be presented in a meticulous and generous manner by writers who believe passionately in the originality and significance of the works about which they have chosen to write. Each book contains a comprehensive and detailed formal description of the work, followed by a critical mapping of the aes-thetic and cultural context in which it was made and that it has gone on to shape. The changing presentation and reception of the work throughout its existence is also discussed, and each writer stakes a claim on the influence their work has on the making and understanding of other works of art.

The books insist that a single contemporary work of art (in all of its dierent manifestations), through a unique and radical aesthetic articulation or invention, can aect our understanding of art in general. More than that, these books suggest that a single work of art can literally transform, however modestly, the way we look at and understand the world. In this sense the One Work series, while by no means exhaustive, will eventually become a veritable library of works of art that have made a dierence.

The tavern was abandoned after the 3/11 earthquake and tsunami. The monkeys still belong to the owner. The current state of the tavern and the monkeys was documented in a 2014 movie by artist Pierre Huyghe.

Kayabukiya Tavern, Wikipedia

Tell me things I won't mind forgetting, she said. Make it useless stuff or skip it.

Amy Hempel

What's it Like to be Almost Like Something Else?

It's a film, about nineteen minutes long, in colour and with sound. It loops. It opens with views of a deserted, largely destroyed town. There are abandoned buildings, some barely standing, others still recognisable from what they used to offer: food, drink, assorted trinkets, probably furniture and a do-it-yourself shop. But it's hard to make out a lot of detail. There are Japanese street signs. Grass has grown through pavement, probably for a year or two already. Piles of trash in black garbage bags are gathered by the side of the road next to abandoned kitchen machines, fridges, air conditioning units. A slight breeze drives a flutter through the plastic barrier tape, now loose and forever purposeless.

Into this post-apocalyptic world drives the camera drone that shares these images with us. It's shooting from hip level, I surmise low flying, maximising the intimacy of encounters, but maintaining indifference in the way only something fully automatic can. The camera drone is on a mission, growing restless and occasionally ramping through compositions. This kind of movement, full of plotted curves, is technically precise, the fulfilment of a powerful dream. Human disappearance seems recent, no more than a few years back, but the emptiness feels thick already. The camera drone moves through a series of ruin tableaux, edited together to suggest a final destination. Suddenly we arrive. The camera is inside a building. No longer flying, its grammar shifts: the detached automation of the exterior sequence gives way to an almost tender intimacy. It feels like the camera has been there before and knows where the good seats are.

The camera tilts down and reveals a little girl. There is something strange about her, as if not quite real. After a certain amount of camera coyness, we realise that the girl is in fact a dressed-up monkey, with white mask, wig and dress. Why? It's altogether uncanny.

The camera is now going to let us watch her do monkey things for the next seventeen, eighteen minutes. Along the way we'll meet a few friends, albeit briefly. There's a cat, a cockroach and some larvae, probably cockroach offspring. And we'll learn a bit about the space, a restaurant with a once-busy kitchen, now looking as though abandoned mid-sentence. It will start to rain; some water will leak in and drip conspicuously. The monkey will (appear to) ponder, be restless, be curious, be cautious. Dressed in her frock, white mask on, she has one or two activities particularly prepped: she retrieves hot towels, puts them on tables and returns with what appears to be liquor. She even does that spinning, dizzying, falling down party trick that children love so much.

Untitled

The monkey of sentiment relies above all on the catalogue. It should be noted, however, that the picture's title never tells its subject.

Charles Baudelaire

It might appear on the window of the gallery, attached to a wall inside, printed in an exhibition catalogue, or on the lips of a gallery attendant or auctioneer. And it circulates in magazines and books and conversations always on behalf of a work. A title is usually composed at the end, but appears like an epigraph. Therefore it is an extra, an embellishment and a precursor, announcing what to expect. A title performs the work and performs on its behalf. A title is, in effect, the work's own avant-garde.

In other words the title becomes a stand-in for the work, trying to become identical with it. Marcel Duchamp referred to the title as an invisible colour, and John Welchman, whose book takes its title directly from Duchamp's formulation, describes three ways in which titles can work:

It's a curious thing, a title. As an artist, I'm often disappointed with my own, thinking they provide too much information or perhaps not enough. Untitled (Human Mask) (2014), by Pierre Huyghe, poises elegantly; it is finely balanced on a tightrope between the too much and the not enough, drawing attention to the divided and contradictory performance of titles. The menu is in two parts and the ingredients contradict. Untitled is a recognised title currently very popular, though probably not as popular as in the 1950s and 60s in New York. Untitled was born of artists resistance to the very idea of titling, and their demand that works be encountered and absorbed without textual entre. Many such artists took their cue from Picasso, who usually refused to title his works, declaring that the works had to speak for themselves. Yet, Untitled does entitle a work of art, and its ubiquity, especially among the high modernist works of the second half of the twentieth century, has effectively defanged it. It feels mannered now, denuded of its power of aesthetic disruption.