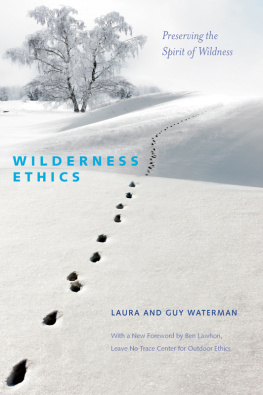

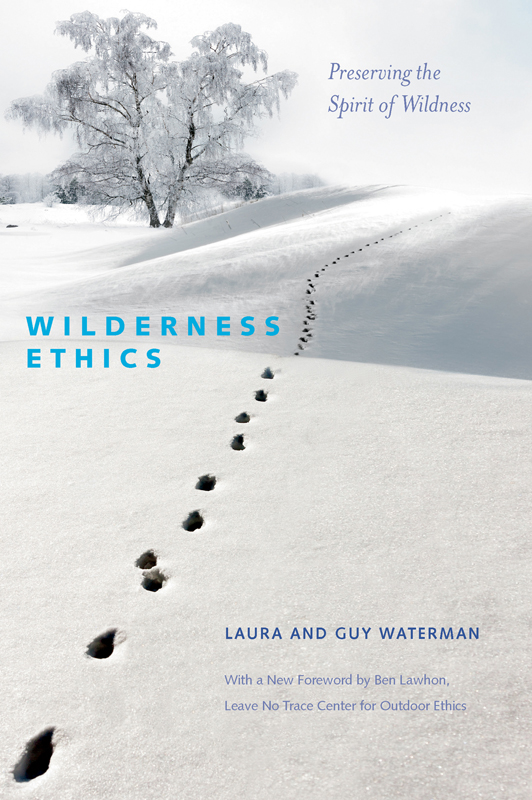

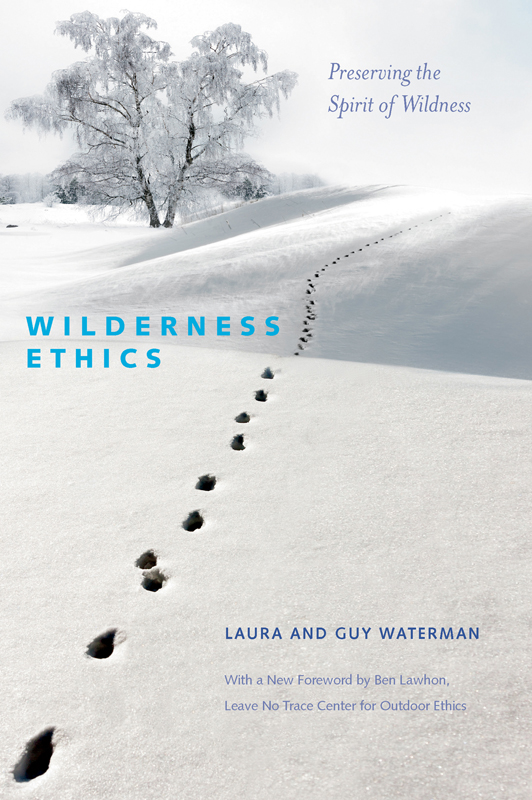

WILDERNESS

ETHICS

Preserving the Spirit of Wildness

New Foreword by Ben Lawhon,

Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics

Original Foreword by Roderick Frazier Nash

Laura and Guy Waterman

Copyright 1993, 2014 Laura & Guy Waterman

1993 Foreword Roderick Frazier Nash

2000 Appreciation Laura Waterman

2014 Foreword Ben Lawhon

Second Edition, 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages.

Published by The Countryman Press

P.O. Box 748, Woodstock, Vermont 05091

Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Cover design by Bodenweber Design

Text design by Karen Savary

Interior art by Beth Krommes

ISBN 0-88150-256-1

1. Wilderness areasUnited States

2. Wilderness areasUnited States Recreational use.

3. Nature conservationUnited StatesMoral and ethical aspects.

4. Nature conservationUnited Statesphilosophy.

5. Wildlife conservationMoral and ethical aspects.

6. Wildlife conservationUnited Statesphilosophy

I. Waterman, Guy.

II. Title

QH76.W38 1993

333.782dc20

ISBN 978-1-58157-267-4

ISBN 978-1-58157-636-8 (e-book)

Extracts from the following sources have been reprinted with kind permission: Tony Goodwin, Rangers in the Night, Adirondack Life , JanuaryFebruary 1990; James North, Preserving the Wilderness Idea, American Hiker , Spring 1990; Steve Page, Speck Pond: Analysis of a Backcountry Shelter, Appalachia Bulletin , December 1972; Mike Usen, Mountain Biking Comes East, Appalachia Bulletin , May 1990; Robert Proudman, Accidents: Search and Rescue of David Cornue and Jane Gilotti, Appalachia , December 1975; Robert Kruszyna, letter-to-the-editor, Appalachia , December 1975; Peter M. Leschak, Facing the Elephant, Backpacker , April 1990; Lisa C. Kernek, Massive Search Turns Up Man Who Says He Wasnt Lost, The Berkshire Eagle , May 2, 1991; letter from Peter Crane to the authors; letter from Sandy Eldridge to the authors; Don Jordan, To Our Nations Fisheries, Izaak Walton League of America, Outdoors Ethics Newsletter , Spring 1991; letter from Allen Koop to L&GW; paper by Robert Kruszyna, The Case Against Search and Rescue; letter from James P. McCarthy to the authors; Alan Smith, The Mount Washington Map Project, Part III, Mount Washington Observatory News Bulletin , Fall 1988; Hugh Neil Zimmerman, From the Presidents Desk, Trail Walker , OctoberNovember 1990; letter from Nathaniel Scrimshaw to the authors.

Dedicated

to a score of our younger friends

Miah and Amanda

James and Scott

Clara and Ben

Emma Rose

Christine and Danny

Anna and Jay

Uli

Justin

Arran and Aslyn

Morgan, Rob, and Liza

Mary Kalisi

and of course Jessie

with the fervent hope that 10 or 20

or 50 years from now, they will still

find wildness and adventure and mystery

and wonder in the mountains.

Also by Laura Waterman

Losing the Garden: The Story of a Marriage

Also by Laura and Guy Waterman

Backwoods Ethics: Environmental Issues for Hikers and Campers

A Fine Kind of Madness: Mountain Adventures Tall and True

Forest and Crag: A History of Hiking, Trail Blazing, and Adventure in the Northeast

Yankee Rock and Ice: A History of Climbing in the Northeast

Contents

THOUGH IT HAS BEEN OVER TWENTY YEARS since Guy and Laura Waterman first published their seminal work Wilderness Ethics , their message about protecting the spirit of wildness is still as relevant today as it was in the early 1990sif not more so. The Watermans spoke not only of protecting the actual physical wilderness but also, and perhaps more importantly, of protecting the spirit of wildness. The key question remains, how can we collectively protect the intrinsic values that wilderness provides given the modern, fast-paced, technology-driven world in which we now live?

The passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act, a magnificent piece of legislation, paved the way to defining the spirit of wildness. The act states that, A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. Reflecting on this eloquent language, one must ask if we have truly left wilderness untrammeled by man or if we have been running amok in the garden in our efforts to make sure wilderness stays wild.

There have always been threats to wilderness, and there will likely be more of them in the future. From overuse to fire suppression to invasive species to a general lack of public awareness, wilderness areas are being affected from both the inside and the outside. Even those of us who claim to be lovers and defenders of wilderness are sometimes unknowingly doing our part to threaten the very thing we aim to preserve.

Despite the challenges facing wilderness and the spirit of wildness, there are signs of hope on the horizon. The very fact that wilderness still exists both on maps and in our minds is encouraging. The notion that renewal of the spirit can come from wilderness is no less important in todays world than it was in decades past. If anything, it is more important now than ever before. From the Watermans beloved peaks of the Northeast to the high peaks of the Rockies to the volcanic cones of the Pacific Northwest, the enduring spirit of wildness is still alive. Though that wild spirit may seem to be just a few remaining embers glowing in the fire, those embers can spark a renewed dedication in the coming years to the protection of the wild places we collectively cherish.

We humans must realize that while wilderness does not exist solely for our benefit, we may be the ones to ensure that wilderness and the spirit of wildness endure well into the future. Our very existence may depend on how well we can provide just enough stewardship to help preserve wilderness while allowing wildness to flourish. Man and wilderness are forever and inextricably linked. What we do outside wilderness impacts the very wildness we treasure. Conversely, what we do inside wilderness also impacts these places we intend to guard. Maybe the answer moving forward is to dig deep within ourselves to better understand why wildness is so critically important. We need to ask ourselves what wilderness means to each of us. We so often care only about things we understand. Thus, the Watermans question What are we trying to preserve must be answered if we are to heighten our sense of what wilderness ethics really means for the wilds of our time, from the deep hardwood forest of the southern Appalachians to the labyrinthine canyons of Utah. For these are the places where the spirit of wildness lives, yet it can live in each of us as well.

Ben Lawhon

Education Director

Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics

SINCE GUY, MY HUSBAND, WALKED out our door and up the mountain on February 6, 2000, not planning to come back down again, I have received a staggering flood of mail. At times it felt overwhelming as I attempted to work my way to the surface of the pile, only to be submerged again when I visited my mailbox at our village post office.

Next page