Contets

Landmarks

Print Page List

ALSO BY JONATHAN NOSSITER

BOOK

Liquid Memory: Why Wine Matters

FEATURE FILMS

Resident Alien

Sunday

Signs & Wonders

Mondovino

Rio Sex Comedy

Natural Resistance

Last Words

Originally published in French as Insurrection culturelle

in 2015 by ditions Stock, Paris.

French edition coauthored by Olivier Beuvelet.

Copyright ditions Stock, 2015

Translation copyright Jonathan Nossiter, 2019

The Art Worlds Patron Satan, by Christopher Glazek, from The New York Times Magazine, December 30, 2014, 2014

The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States.

The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited.

Production editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

Text Designer: Jennifer Daddio / Bookmark Design & Media Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

For information write to Other Press LLC, 267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016.

Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Nossiter, Jonathan, author.

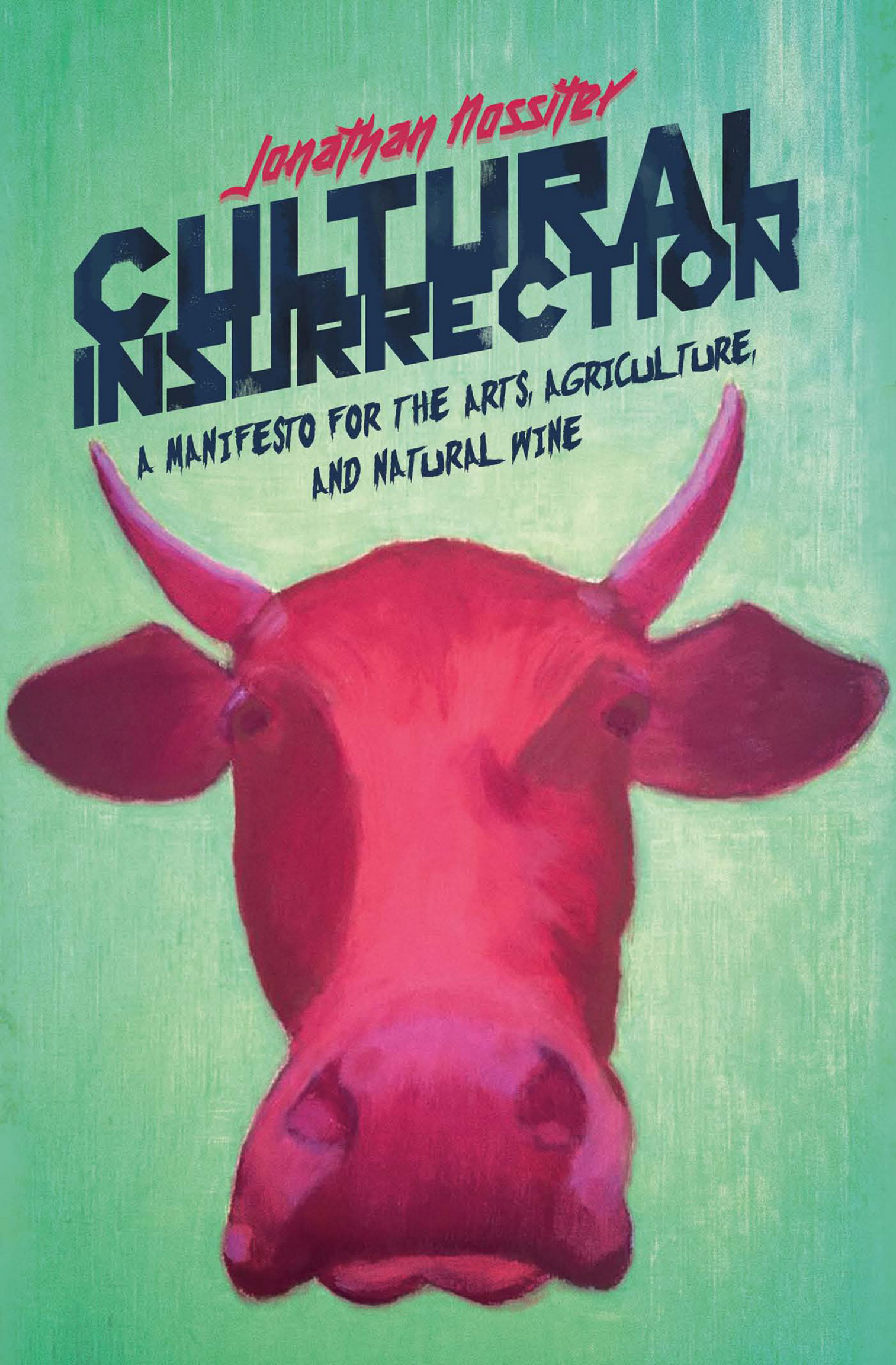

Title: Cultural insurrection / Jonathan Nossiter.

Other titles: Insurrection culturelle. English

Description: New York : Other Press, [2019] | Originally published in French as Insurrection culturelle in 2015 by editions Stock, Paris. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018044922 (print) | LCCN 2018046776 (ebook) | ISBN 9781590518274 (ebook) | ISBN 9781590518267 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Art and popular culture. | Organic viticulture. | Wine and wine making.

Classification: LCC N72.S6 (ebook) | LCC N72.S6 N67513 2019 (print) | DDC 701/.03dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018044922

Ebook ISBN9781590518274

v5.4

a

For my children Miranda, Capitu, and Noah and for our farm, Fattoria La Lupamay they all have thriving futures

Contents

Preface

T HIS BOOK is intended for those who never considered wine of any remote interest.

But its intended equally for wine lovers.

If youre among the former, then Ill ask you to imagine wine simply as a radical (that is, deeply rooted) metaphor for culture, art, and politics. If youre one of the latter, I ask you to disregard what you know (or think you know) about the aesthetics of wine and look at it as a radical metaphor forculture, art, and politics.

Im a film director, so my first concern should be cultural. But before that Im a citizentechnically of the United States and Brazilin upbringing a citizen of France, Italy, Greece, and England. For any twenty-first-century citizen anywhere, beyond the cultural lies a deeper concern that necessarily has to condition and supersede any other: the ecological-existential.

In looking at a paradoxhow the doomsday state of agriculture has provoked a joyous response from a utopian fringe of wine farmersthis book proposes a reimagining of aesthetic, political, and cultural questions as essentially ecological ones.

And the reverse: how no environmental question should be considered separately from culture and aesthetics, as well as politics.

One

The New Cultural Hell (Cast Out of Purgatory)

I N 1974, a year before he was murdered, Pier Paolo Pasolini, taboo-busting filmmaker, poet, novelist, journalist, relentless antifascist, and one of the last genuinely public intellectuals anywhere in the worldwas invited by RAI, the Italian public broadcasting company, to narrate a visit to the model fascist town of Sabaudia.

Though the producers were expecting a violent denunciation of fascist-era city planning, they shouldve known that Pasolini was above all a free man, free even from his own biases: the clearest sign of intellectual courage. In the televised report, we follow him through the streets of this coastal town, sixty miles south of Rome, and we hear him explain: In fact, there isnt anything fascist about this model city. The buildings here are all built on a human scale. You feel in harmony wherever you go.

The TV film crew, surprisingly attentive to his subtlest gesture, follows him onto the sand dunes. As the February wind rakes his hair dramatically, Pasolini turns to the camera and addresses the viewer. But he also speaks to the television crew, whom he clearly considered his colleagues. This is not a famous intellectual condescending to technicians and the public. This is a profoundly compassionate poet terrified by the world, urging every sentient being around him to rethink what they see. His intensity and instinctive egalitarianism produce an intimacy between viewer and onscreen actor unlike anything were accustomed to from the sterilizing lens of a TV camera.

The fact is, the fascists even screwed this up. At the end of the day, they were just a bunch of criminals who came to power. They failed to leave a lasting stamp on any aspect of Italian life. His gaze then seems to bore into each one of us.

Today, in 1974, its the opposite. Our government is democratic. But this consumer society has managed to homogenize culture in a way the fascist government was never able to.

W HAT WOULD HE SAY TODAY , over forty years after his death, about the state of culture? Is there any national network anywhere that would put a renegade poet in front of a prime-time audience? And are there still artists and intellectuals who can raise their voice in a forum that commands an audience as complete as television did in 1974? Or as the agorathe marketplace of ideas and commerce in Athens at the inception of a democracydid 2,500 years ago?

What has happened to the status of public intellectuals? How can they address the general public today? How can they bring culture to life as an affirmation of subjective freedom? What popular venue is left for them to express culture as a joyous invention of aesthetic forms, as a way to question the mechanisms of power, as a guarantee of our collective freedoms? The infinite compartmentalization of the Internet is one of many guarantees that this has become virtually impossible.

The dream of every totalitarian state has been to silence artists and make them invisible. By the nature of their activity, artists are uncontrollable. This makes them the truest counterweight to any exercise of power. Pasolini was prophetic in his understanding of how an omnivorous consumer society has managed surreptitiously, even unintentionally, to accomplish what the fascists only dreamed of.