PUERILITIES THE LOCKERT LIBRARY OF POETRY IN TRANSLATION EDITORIAL ADVISOR: RICHARD HOWARD For other titles in the Lockert Library, see

PUERILITIES

Erotic Epigrams of

The Greek Anthology TRANSLATED BY DARYL HINE PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright 2001 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton,

New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY Translations of

Strato, I, CC, CCVI, CCVII, and CCXLII;

Meleager, XCV and CXXII;

Rhianos, XCIII;

Diodes, IV;

Anonymous, XVII and CXLV;

Scythinus, XXII; and

Glaucus, XLIV, originally appeared in the

Columbia Anthology of Gay Literature and are used here by kind permission of the editor, Byrne R. S. Fone.

All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Greek anthology. Book 12. cm. (Lockert library of poetry in translation)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-08819-5 (alk. paper) ISBN 0-691-08820-9 (pbk. : alk paper) 1. : alk paper) 1.

Erotic poetry, GreekTranslations into English. 2. Epigrams, GreekTranslations into English. I. Hine, Daryl. Title. III. III.

Series.

PA3624.E75 P84 2001

881.010803538dc21 00-066885 This book has been composed in Adobe Garamond The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of

ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper) www.pup.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The Lockert Library of Poetry in Translation is supported by

a bequest from Charles Lacy Lockert (18881974) For Jerry You mavericks, what language should explain The derivation of the word makes plain: Boy-lovers, Dionysius, love boys You cant deny itnot great hobblehoys. After I referee the Pythian Games, you umpire the Olympian: The failed contestants I once sent away You welcome as competitors today.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

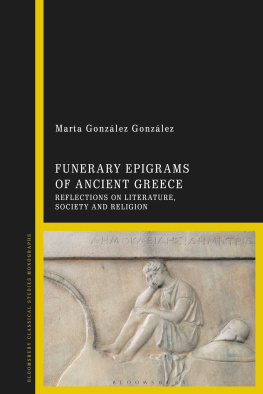

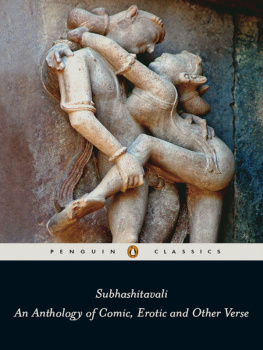

THE TWELFTH book of

The Greek Anthology compiled at the court of Hadrian in the second century A.D. by a poetaster Straton, who like most anthologists included an immodest number of his own poems, is itself a part of a larger collection of short poems dating from the dawn of Greek lyric poetry (Alcaeus) down to its last florescence, which survived two Byzantine recensions to end up in a single manuscript in the library of the Count Palatine in Heidelberghence its alternative title,

The Palatine Anthology, usually abbreviated to

Anth. Pal. This particular, indeed special, collection contained in Book XII subtitled

The Musa Paedika or

Musa Puerilis, alternately from the Greek word for a child of either sexand girls are not wholly absent from these pagesor the Latin for boy, consists of 258 epigrams on various aspects of Boy Love or, to recur to the Greek root, paederasty.

Some of these poems are by the greatest poets of the Greek language, such as Alcaeus and Callimachus; many are by less well known but nonetheless polished writers, such as Meleager, Asclepiades, Rhianus, and Strato himself; many, these not the least worthy, are anonymous. Their tone varies from the lighthearted and bawdy to the grave and resigned. The overall effect is one of witty wistfulness rather than rampant, reciprocated lust, of longingwhat the Greeks called pothosrather than satisfaction, and also of regret. As happy, let alone domestic, love has occasioned very little poetry at any time, as passion almost always sounds a plaintive notehere at least seldom rising into the desperate wail we hear, for example in Catulluswe might well seek an explanation in the nature of desire itself, on the Platonic model envisaging a forever unattainable, divine object, of which all earthly affection is merely a mirror, however delightful and sometimes delusive. That this undercurrent of spiritual pothos is far from conscious in these poems needs no comment; but it is implicit in the very nature of Love or Eros itselfor, as so often familiarly personified, Himself. That the objects of such passion were masculine and for the most part at least comparatively juvenile is an historical fact and, like all facts, an accident.

The fact that other later poets in another though not wholly dissimilar Christian, heterosexual tradition, such as notably Dante, Petrarch, Chrtien de Troyes, and Goethe, to mention only a few, found transcendence in the eternal feminine instead is also of but incidental interest. Fashions in passion change, like fads in anything else, and while we are given to thinking our own modes and norms of conduct both universal and solely acceptable, the merest glance at history, literature, and anthropology will show us otherwise, as will a peep behind the faade of respectable behavior. The family unit, however defined, is itself a comparatively recent invention or convention; for whereas the bond of mother and child remains for our kind as for each of us the earliest form of attachment, among adultsand we should never forget that adulthood began much earlier in earlier timesit was the group, the horde, or that most decried yet most prevalent group, the gang. Gangs, first I suppose for hunting game, are to be found not only on streetcorners but in board rooms, the most common and powerful type of the gang being the committee. The group for and within which these poems were composed and circulated was neither a gang nor a committeeitself a martial term originallybut a court, neither an academy nor yet an institute; these rather than those high-flown heterosexual fantasies of the twelfth century represented the first form quite literally of courtly love. Love, surrounded by the simpering Graces, And Bacchus are ill-suited to straight faces.

Love, love, love, Eros, personified and impersonal, bitter yet sweet, now an infant on his mothers lap, now an adolescent boy winged with fanciful desires and armed with the playthings of youth, his arrows less fatal than those of Apollo and Artemis but also less painless, inflicting an incurable festering wound, is the paramount deity and pervasive, prevalent spirit of these poems. Even almighty Zeus is seldom mentioned save as the grasping, aquiline lover of Ganymede, the paradigmatic catamite. Eros at this period, always, at least in his origins, physical, figured as Aphrodites son, fatherless, older in some respects than She, urge or demiurge, impulse and illusion, never absent yet often unnamed in these lines, prevails: Amor omnia vincit. Yet love not only conquers; he, she, or it oppresses, teases, and torments. Unfavorably compared by some flattering suitors to certain of his lovelier mortal incarnations, Eros is sometimes also said to suffer from the passion he provokes. From time to time, if only hopefully, the tables may be turned on the mischievous little monster, in a role reversal with obvious implications: This is the boy to be enamored of, Young men, a new love superior to Love.

LIX [Meleager] Thief of hearts, why jettison your cruel Arrows and bow and, weeping, fold your wings? Invincible Myiscus looks must fuel Repentance for your previous philanderings. CXLIV [Meleager] Our modern sense of such things is if anything more graphic, yet we will ask in vain what, exactly, these people did, sexwise. Ambiguous hints and metaphors are all we are given. The divine yet very real generative impulsefor the notion of an immaterial divinity, though hardly unknown, if as mathematically conceived by Plato, seemed altogether strange to popular religion and our authors alike, at once down to earth and highfalutininfallibly overwhelms both its object and its vessel, even as it informs its verbal medium. The sentiments of these juvenescent expressions are, within a persistent convention alien to us, as conventional as those on any Valentine card, though more ingeniously and frankly couched. Besides Eros himself and his mother, the divinized entities most mentioned are Dionysus (Bacchus)Drinkand the Graces, physical and social, surrounding and supporting Beauty.

Next page

Erotic Epigrams of

Erotic Epigrams of