Life of School The - How to Survive the Modern World

Here you can read online Life of School The - How to Survive the Modern World full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: The School of Life, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:How to Survive the Modern World

- Author:

- Publisher:The School of Life

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

How to Survive the Modern World: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How to Survive the Modern World" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

How to Survive the Modern World — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How to Survive the Modern World" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

the Modern World

Since the middle of the eighteenth century, beginning in Northern Europe and then spreading to every corner of the world, people have become aware of living in an age radically different from any other. With a mixture of awe and respect, trepidation and nostalgia, they have called this the modern age or, more succinctly, modernity. We are now all inhabitants of modernity; every last hamlet and remote island has been touched by the outlook and ideology of a new era.

The story of our emergence into the modern world can be traced in politics, religion, technology, fashion, science, art all of which have contributed to an alteration in consciousness, to a change in the way we think and feel. Becoming modern has involved changes across many parts of our lives.

A NASA technician measures a RM-10 model booster, 1951.

Perhaps the single greatest marker of modernity has been a loss of faith the loss of a belief in the intervention of divine forces in earthly affairs. All other ages before our own held that our lives were at least half in the hands of gods or spirits, who could be influenced through prayer and sacrifice and who required complex forms of worship and obedience. But we have increasingly put our energies into understanding natural events through reason: there are no more omens or revelations, curses or prophecies; our futures will be worked out in laboratories, not temples. Even the nominally religious will demur to highly trained physicists and cancer specialists. God has died and modernity has killed Him.

Pre-modern societies envisaged history in cyclical terms: there was no forward dynamic to speak of; one imagined that things would always be as bad or as good as they had ever been. There was no more change in human affairs than there was in the seasons. Empires would wax and wane; periods of plenty would alternate with seasons of dearth, yet the fundamentals would remain. To be modern is to believe that we can continually surpass what has come before: national wealth, knowledge, technology, political arrangements and, most broadly, our capacity for fulfilment, seem capable of constant increase. Weve severed the chains of repetitive suffering. Time is not a wheel of futility; it is an arrow pointing towards a perfectible future.

We have replaced gods with equations. Science will give us mastery over ourselves, over the puzzles of nature, and ultimately over death. Dense calculations and the electrical spasms inside microscopic circuits will allow us to map and know the universe. It is only a matter of time before we work out how to be immortal.

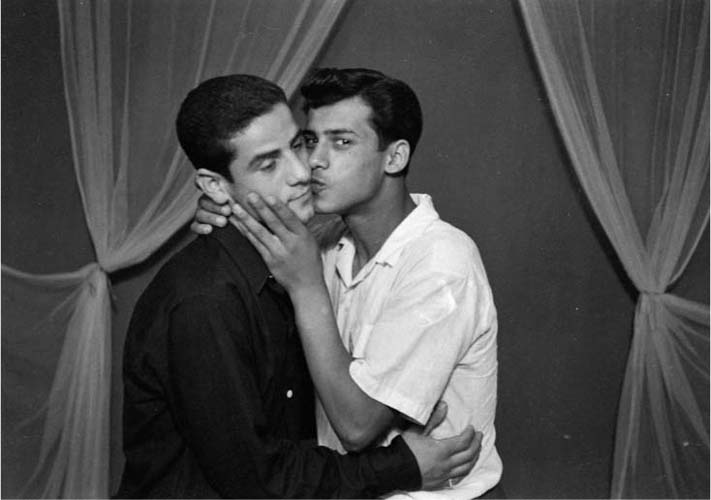

Akram Zaatari, Excerpt from Objects of Study/ The Archive of Studio Shehrazade/ Hashem el Madani: Studio Practices 2006. Photograph of Tarho and el Masri, Saida, 1958.

To be modern is to throw off the claims of history, precedent and community. We will fashion our own identities rather than being defined by families or tradition. We will choose who to marry, what job to pursue, what gender to identify as, where to live and how to think. We can be free and, at last, fully ourselves.

We are Romantics; that is, we seek a soulmate, an exemplary friend who can at the same time be an intrepid sexual partner, a reliable co-parent and a kindly colleague. We are in revolt against coldness and emotional distance. We refuse to remain in unhappy unions that no longer possess the sense of connection of the early moments. We will move boulders to find a spiritual twin.

Gustave Caillebotte, Le Pont de lEurope, 1876.

We have had enough of the narrowness of village life. We dont want to go to bed when the sun sets or limit our acquaintances to the characters we went to school with. We want to move along with eighty-five per cent of the population of modern nations to the brightly illuminated city, where we can mingle in crowds, observe faces on underground trains, try out unfamiliar foods, change jobs, read in parks, rethink our hair, visit museums and sleep with strangers.

We are modern because we work not only to earn money, but to develop our individuality, to exercise our distinctive talents and to find our true selves. We are on a quest for something our ancestors would have thought paradoxical: work we can love.

Pre-modern people lived in close proximity to nature; they knew how to recognise shepherds purse and make something edible out of pineapple weed. They could tell when sparrows showed up and what sounds short-eared owls make. They venerated nature as one might a deity. But moderns dont tremble before the night sky or feel a need to give thanks to the rising sun. We have freed ourselves from our previous awe at natural phenomena; we are alive to the sublimity of technology rather than of waterfalls. The emblematic modern locale is the twenty-four-hour supermarket, brightly lit and teeming with the produce of the seven continents, proudly defying the barriers of geography and of the night. We will eat pomegranates from Jamaica and dates from the Sahel.

For most of history, our maximum speed was set by the constraints of our own feet, or at best, the velocity of a horse or a sailing ship. It might take three weeks to tramp from London to Edinburgh; four months to sail from Southampton to Sydney. In eighteenth-century Spain, the majority of people died within twenty-five kilometres of where they had been born. Now, nowhere is further than twenty-six hours away and the Voyager 1 probe is hurtling at seventeen kilometres per second, 21.2 billion kilometres away from its launch planet, on its way to explore interstellar space.

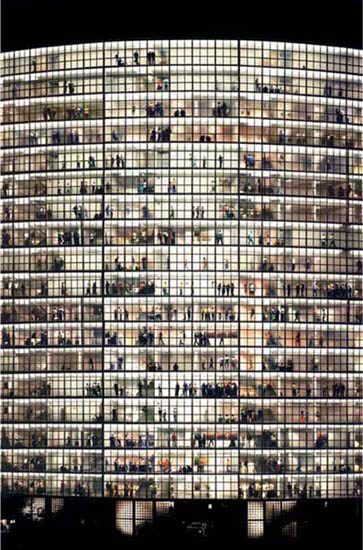

Andreas Gursky, May Day V, 2006.

Much of the transformation of modernity has been exciting; thrilling, even. Fibre-optic cables ring the Earth, satellites guide us across cities, new ideas overthrow rigid assumptions, airports are conjured from the ground and colossal energies are unleashed by the Promethean forces of chemistry and physics. The word modern still suggests a state of glamour, desire and aspiration.

But at the same time the advent of modernity has been a story of tragedy. We have bought our new freedoms at a very high price. We have never been so close to collective insanity or planetary extinction. Modernity has wreaked havoc on our inner and outer landscapes. We can pick up on aspects of the catastrophe in seven areas.

The late-nineteenth-century French sociologist mile Durkheim first made the sobering discovery of an essential difference between traditional and modern societies. In the former, when people lived in small communities, when the course of ones career was understood to lie in the hands of the gods, and when there were few expectations of individual fulfilment, at moments of failure, the agony knew bounds; reversal did not seem like a verdict on ones whole value as a human being. One never expected perfection, and did not respond with self-laceration when mishaps occurred. One simply fell to ones knees and implored the heavens. But Durkheim knew that modern societies exacted a far crueller toll on those who judged themselves to have failed. No longer could these unfortunates blame bad luck; no longer could they hope for redemption in a next world. It seemed as if there was only one person responsible and only one fitting response. As Durkheim showed, in perhaps the largest single indictment of modernity, suicide rates of advanced societies are up to ten times as high as those in traditional ones. Moderns arent only more in love with success, they are far more likely to kill themselves when they fail.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «How to Survive the Modern World»

Look at similar books to How to Survive the Modern World. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How to Survive the Modern World and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.