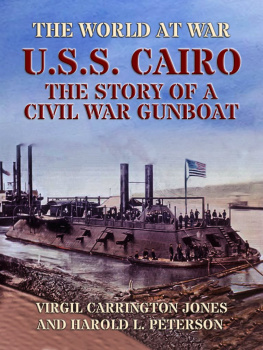

U.S.S. Cairo

Virgil Carrington Jones and Harold L. Peterson

Jones and Peterson, as the readers of this booklet will discover, have written of the Cairo and her treasure trove of artifacts with keen insight and understanding. Their accounts will spark the readers interest, and, in conjunction with the salvaged objects themselves, lead to a better understanding of how bluejackets lived and fought in our Civil War.

Edwin C. Bearss

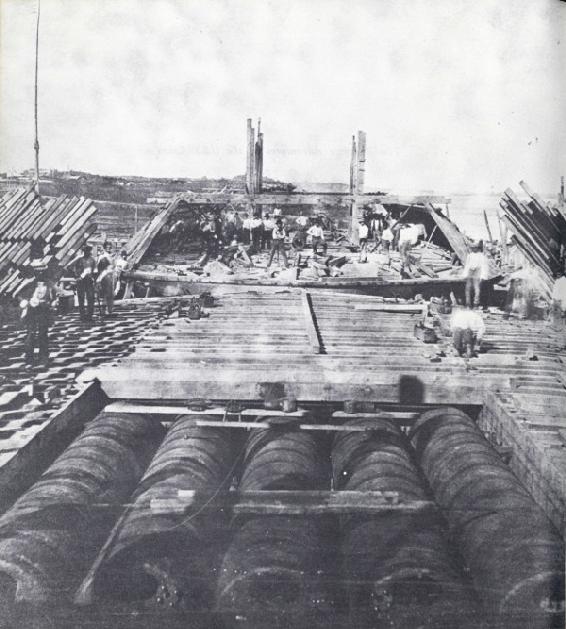

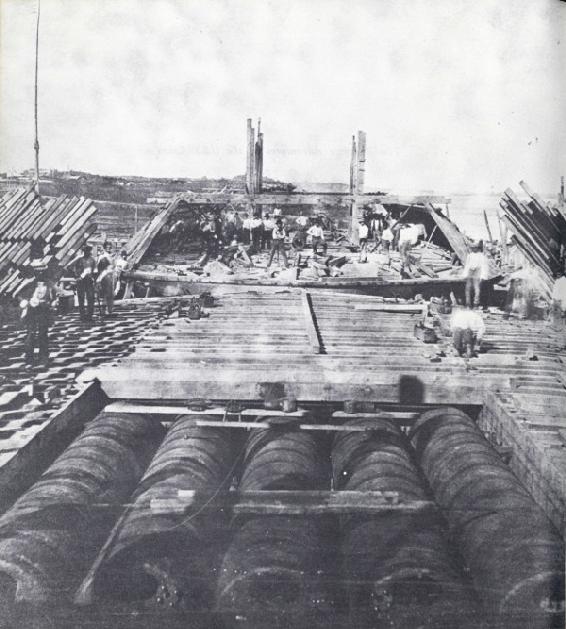

Eads ironclads under construction at the Carondelet shipyards near St. Louis. The Cairo , although not built here, would have looked much the same at this stage. National Archives

Some men and some ships seem fated for bad luck. It was the Union ironclad Cairos fate to have as her second and last captain a man who, although a hard worker, was a repeated slave to misfortune. Three of the vessels on which he served, their names all beginning with the letter C, went to the bottom in the order namedthe Cumberland, the Cairo, and the Conestogano matter if he was credited with gallantry and exonerated of blame by some of his superiors.

Thomas O. Selfridge, Jr., son of the commandant of the Navy Yard at Mare Island, Calif., was a member of seafaring family. He was dedicated and ambitious, but, as fate would have it, he served mostly on doomed vessels and was unable to get along with his men. Perhaps his fellow seamen had reason to be displeased with him, for he seemed always to flirt with disaster, barely escaping further serious mishap early in the war while experimenting with the crude submarine Alligator on a trial run from the Washington Navy Yard. So bad was his luck that the Cairos career ended just 3 months to the day after Selfridge first stepped aboard her.

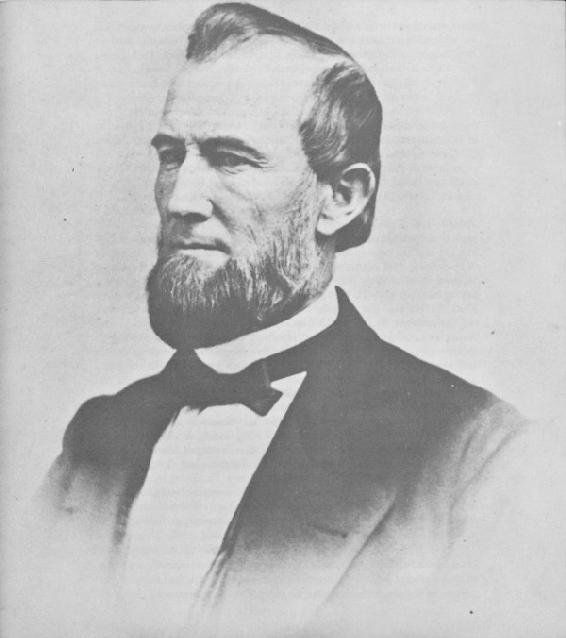

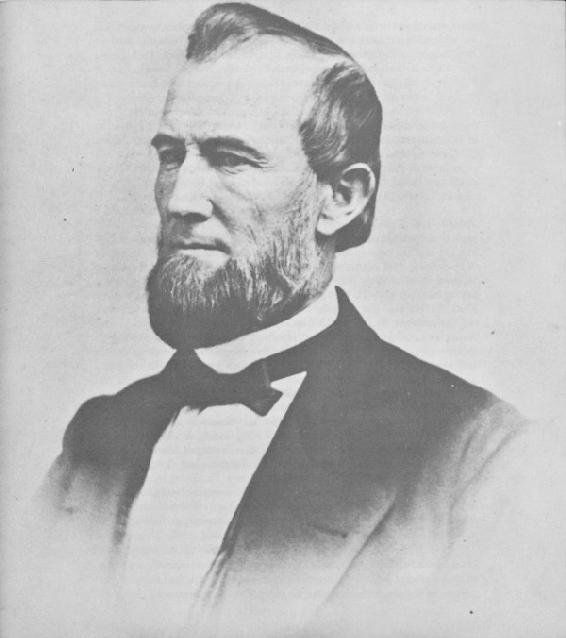

The Cairo was one of the weapons designed by the North to wrest the lower Mississippi River away from the South, a move decided on early in the war as part of a program of vigorous action needed to bring victory. One of those who expounded the strategy was James B. Eads of St. Louis, Mo., who had retired at 37 after making a fortune salvaging wrecked craft on the Western rivers. An engineer known to every riverman on the Mississippi, he had had long experience at the business of designing and building boats.

Soon after the fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Eads was called to Washington to present his recommendations at a Cabinet meeting. His strategy seemed simple: seize control of the lower Mississippi, the main channel through which flowed the Souths food supplies, and leave open as avenues of commerce in the Mississippi basin only the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers and the railroads from Louisville to Nashville and Chattanoogaall of which could be easily controlled. The result, as he saw it, would be starvation for the Confederates in less than 6 months. To carry out his plan, he urged the North to build a fleet of river gunboats, an inland navy.

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles liked Eads ideas, but, before they could be acted upon, a brief flareup of jealousy between the War and Navy Departments created interference. At this time the Army had jurisdiction over the inland waters, while the Navys only responsibility was to furnish guns and crews for the vessels the Army acquired. Secretary of War Simon Cameron had initially thought Eads proposals absurd, but when it seemed that the Navy Department intended to go ahead with them, he reversed himself and insisted that the fitting out of river gunboats be handled by the Army. Camerons vacillation created so much confusion that prospects for an early decision in the matter were now remote. Thus stymied, Eads left Washington.

It was mid-summer before Eads noticed advertisements in St. Louis newspapers inviting bids to build the gunboats. According to the specifications, the vessels were to be 175 feet long, with a 50-foot beam, and to draw 6 feet of water. They would have flat bottoms, with three keels, and an oblong casemate sloping up to a flat spardeck, 45 in front and 35 on the side. The forward end was to be pierced for three guns, the port and starboard beams for seven guns each, and the stern for three guns. (As built, however, there were four ports on each side of the casemate, three on the forward face, and two on the after face.)

Each vessel was to be fitted out with a paddle wheel, two engines, five 36-inch boilers 24 feet long with a firebox under each, and two 44-inch chimneys 28 feet high. They would have plain cabins with two staterooms, two messrooms, and eight staterooms for officers, as well as suitable magazines, shell rooms, and shot lockers. Officers quarters were to be equipped with berths, bureaus, and washstands.

When bids were opened August 5, 1861, Eads was the lowest of seven: In it he agreed to build four to 16 of the boats, at a price of $89,600 each, by October 5 of that year. If not delivered on time, he would forfeit on each vessel $600 per day it was late. The contract Eads signed called for seven gunboats, moved the delivery date to October 10, and reduced the forfeit to $250 per day. Every 20 days, superintendents appointed by the Government would estimate the amount of work done, and the Treasury would pay Eads 75 percent of the estimate. The Government retained the right to suspend work at any time, and it was definitely specified that no part of the contract was to be sublet. Government representatives would inspect the material used in constructing the vessels and reject all considered defective. To his benefit, Eads obtained an agreement that the Government would require no change in specifications which might delay completion of the contract as specified.

James B. Eads.

Library of Congress

Eads began work immediately, starting four of the vessels at the Carondelet Marine Ways on the outskirts of St. Louis, and three at the Marine Railway and Ship Yard at Mound City, Ill. Labor troubles set in early. Although wages were comparable with rates prior to the war, workers threatened to strike for more money. The contractor in the meantime advertised for additional boat carpenters, offering to pay $2 per 10-hour day and 25 cents per hour overtime.

By the end of August, Eads had about 600 men and 12 sawmills at work on the seven hulls. The first estimate of work done, submitted to the Government on August 27, amounted to $58,315 and was accompanied by a statement that the smallness of the sum did not mean that matters were not being pushed with vigor. In mid-September, when Eads sent in a second estimate, he complained of not having received even $1 on a contract involving an outlay of nearly $700,000. He said that, despite the inconvenience brought upon him by the Government, he was still confident he could fulfill his contract. Newspapers came to his defense, reporting that, without any money in advance, he had 800 workmen on the two jobs, as well as one steamboat and four barges engaged in transporting lumber from sawmills in Missouri, Illinois, Ohio, and Kentucky, and along the Missouri River. But even the reporters inspecting the work doubted that the vessels would be ready on schedule.