Contents

Guide

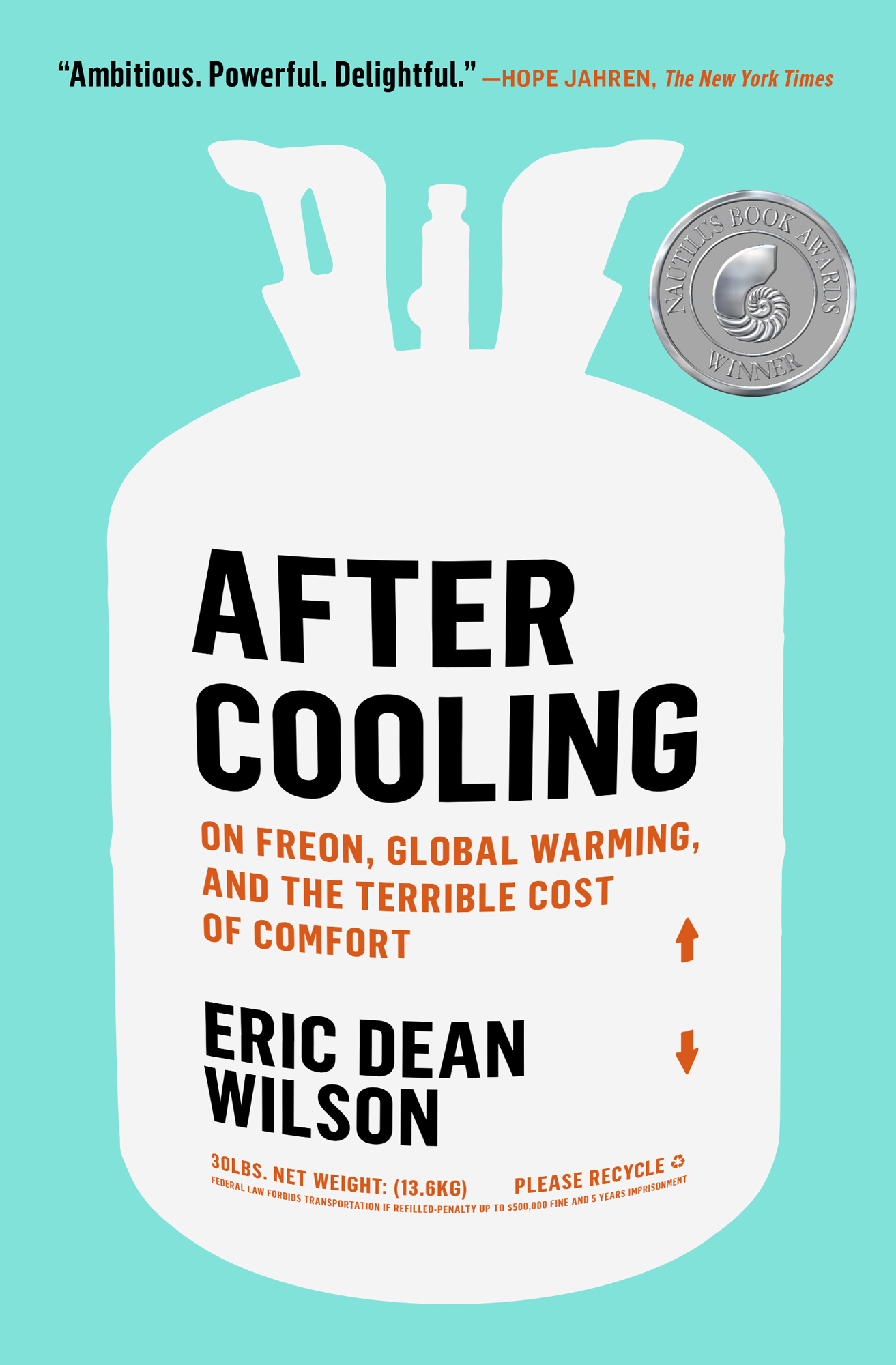

Ambitious. Powerful. Delightful.Hope Jahren, The New York Times

After Cooling

On Freon, Global Warming, And the Terrible Cost of Comfort

Eric Dean Wilson

30LBS. Net Weight: (13.6KG)

Please Recycle

Federal Law Forbids Transportation if Refilled-Penalty up to $500,000 fine and 5 Years Imprisonment

Praise for After Cooling

As entertaining as it is edifying. Youll learn what put a hole in the ozone layer, how the Rivoli movie theatre in New York inaugurated our present ice age, who in this country is still hoarding Freon, how air-conditioning is exacerbating heat wavesand lots of other ecological horrors. This is a brilliantly researched book.

Edmund White, National Book Critics Circle Awardwinning author of City Boy

Deftly persuasive Wilson invites the reader into deep existential discussions.

Hope Jahren, The New York Times

After Cooling is a deeply discomforting bookand thats the point. Eric Dean Wilsons message, which could not be more timely, is that we need to rethink how we live and what we want.

Elizabeth Kolbert, Pulitzer Prizewinning author of Under a White Sky

Excellent.

Rolling Stone

Meticulously researched and engagingly written, After Cooling is essential reading for the planetary crisis.

Amitav Ghosh, bestselling author of The Great Derangement

As much sociopolitical commentary as history of science Wilson digs deeply into the linkages between Western desire for material comfort and racial oppression, including critiques of capitalism and profit-seeking industry.

Science

Thoughtful, rigorous, and rich with lessons for our warming world.

Robert Moor, bestselling author of On Trails

A fascinating narrative of technological innovation and environmental destruction.

The Baffler

A spectacularly interesting read! After Cooling offers a lively history of air-conditioning and explores all the complexities of the fight over Freon.

Eula Biss, National Book Critics Circle Awardwinning author of On Immunity

A knockout debut by a gifted writer.

New York Journal of Books

Wilsons magnetic writing is undeniable. Blending history and science, along with a tapestry of literature, philosophy, poetry, and pop culture, Wilson explores the origins of mechanical cooling and how it became a ubiquitous part of American life, as well as a devastating agent of ozone depletion and climate change.

Booklist

Ingenious An unsettling exploration of the history and cultural influence of air-conditioning [as well as] a philosophical attack on the free market and capitalism, which drive our obsession with personal comfort.

Kirkus Reviews

A tour de force on the steep costs of living in a world that prioritizes personal comfort As urgent as it is idealistic Wilsons impressive take offers climate-minded readers much to consider.

Publishers Weekly

A masterful piece of creative nonfiction A must read.

The Raven Book Store (Lawrence, Kansas)

To my parents

The sea rises, the light fails, lovers cling to each other, and children cling to us. The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out.

James Baldwin, Nothing Personal (1964), published one year before the Presidents Science Advisory Committee would release a report that the rapid consumption of energy by overdeveloped economies is unwittingly conducting a vast geophysical experiment that could be deleterious from the point of view of human beings

Prelude This Business of Destruction

Even now the devastation is begun,

And half the business of destruction done.

Oliver Goldsmith, The Deserted Village (1770)

I had no idea where we were headed, only the slightest of what we were after. I was driving. We were late. I was speeding through downtown Memphis in a borrowed minivan with no more than a vague idea of our meeting spotsome park along the Mississippi. (A park? I thought. In broad daylight?) Sam, at ease in the seat next to me, seemed unaware of my growing discomfort. His thumbs lightly drummed the armrest. I accelerated through a yellow light. Id waited months to shadow him on one of his deals, and now I was sure I was about to botch it.

A phone rangSams cell. He put the call on speaker as I turned left along the river. It was the client. He was running a few minutes late. (My fingers loosened their grip on the wheel.) But not to worry, the client added, his tone less assuring than annoyed, as if hed heard a note of doubt. He was bringing us the stuff.

Sam smiled. He held the phone in the air between us, and I opened my mouth to ask for directionsId made a half dozen U-turns looking for the spotbut stopped. The client sounded impatient. He was already doing us a favor by driving over from Arkansas. I didnt want to ask too much.

At least, that was what I told myself at the time. To be honest, I was afraid that, in speaking even a word over the phone, I would reveal in the timbre of my voice what I was attempting to hide: that I wasnt an air-conditioning mechanic or refrigerant reclaimer, that I wouldnt know a tank of Freon from propane, that I didnt work with my hands (unless you count typing, which you shouldnt), that I was too feminine (a familiar fear for a queer like me who grew up in the US South, a fear that says as much about misogyny as homophobia), or that I preferred a book to a ball game. I was afraid that, in answeringin unconsciously revealing any one of theseI might blow the deal.

So I said nothing. Sam ended the call.

What did I know of refrigerant? Not much at the time. But I was learning.

Id learned, for instance, that the rise of modern air-conditioning in the early twentieth century had depended, in part, on the invention of a chemical: the refrigerant commonly known as Freon. I knew that Freonthe go-to for any kind of mechanical coolinghad reigned for fifty years until, in the 1980s, scientists found that it destroyed the ozone layer, after which its production was banned. I knew, too, that Freon, when released into the atmosphere, acts as a highly potent greenhouse gasfar more potent than carbon dioxide. This double power to destroy our climate makes Freon, in Sams words, pound for pound the worst stuff on the face of the planet. Good thing, then, that no one makes it anymore. And yet, thanks to Sam, I also knew that despite that fact, there was still a hell of a lot of Freon left in the United States.

At a red light, I looked over at Sam, whod snapped into business mode. Hed pulled a stack of forms from a black briefcase, and, balanced on his knee, his phone lay open to an email. His head swiveled sharply from phone to page, phone to page, as he scribbled something on the top form, using the length of the briefcase to brace himself as I took the car roughly over railroad tracks. He was silentunusual for Samfocused on whatever it was he was doing.

At last, I found what I hoped was the parknot so much park as parking lotoverlooking the Mississippi. It was still early morning, the lot empty. I pulled in and shut off the car. Sam and I sat in silence. The engine ticked.

Modern refrigerantthat is, the gas in fridges, freezers, air conditioners, and anything else that cools mechanicallyhas come to us in waves. The first arrived in the 1930s with the development of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), better known as the Freons (after their DuPont trademark), a family of industrial chemicals each with a boiling point below room temperature, a property that makes it possible to augment the cooling power that comes from evaporating a liquid. Confined within the coils of a fridge or air conditioner, the refrigerant is compressed into a liquid that cycles through a series of circuits. A sudden ease in pressure within the coils causes the refrigerant to absorb the heat around it and vaporize (boil), which lowers the temperature of the surrounding air. Thus, cooling.