Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

This is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

As of the time of initial publication, the URLs displayed in this book link or refer to existing websites on the Internet. Penguin Random House LLC is not responsible for, and should not be deemed to endorse or recommend, any website other than its own or any content available on the Internet (including without limitation at any website, blog page, information page) that is not created by Penguin Random House.

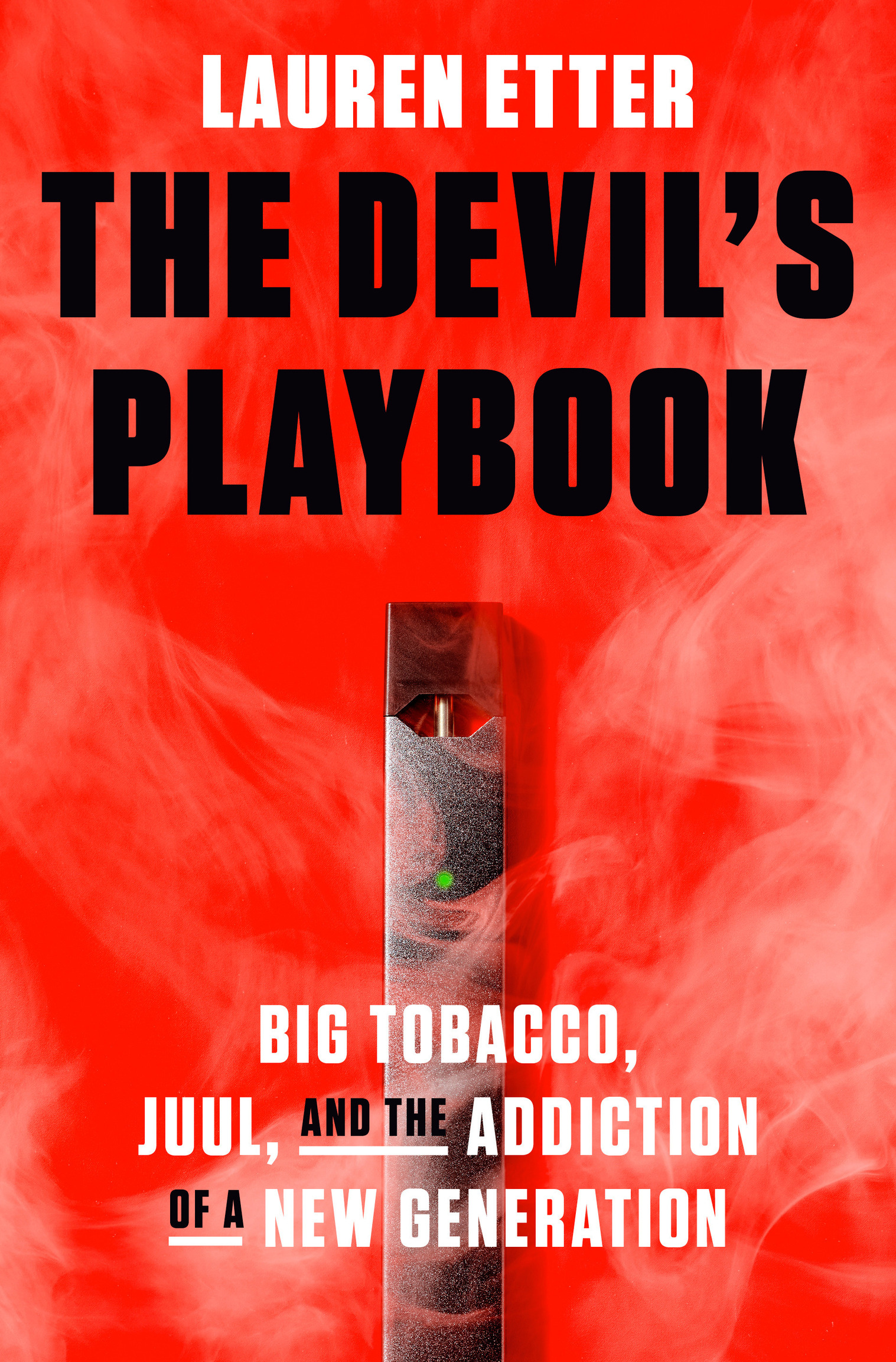

Copyright 2021 by Lauren Etter

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Crown and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Etter, Lauren, author.

Title: The Devils playbook / Lauren Etter.

Description: First edition. | New York : Crown, [2021] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021004354 (print) | LCCN 2021004355 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593237984 (hardcover) | International edition ISBN 9780593240687 | ISBN 9780593237991 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Vaping. | Substance abuse. | Cigarette industry. | Tobacco industry.

Classification: LCC HV5748 .E57 2021 (print) | LCC HV5748 (ebook) | DDC 338.7/67973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004354

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004355

Ebook ISBN9780593237991

crownpublishing.com

Designed by Debbie Glasserman, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Christopher Brand

Cover photograph: Jens Mortensen Photography

ep_prh_5.7.0_c0_r1

Contents

PROLOGUE

ON THE SIDE OF THE ANGELS

The loveliest trick of the Devil is to persuade you that they dont exist!

CHARLES BAUDELAIRE

On Sunday, November 14, 1999, Steven Parrishs airplane touched down at the Luis Muoz Marn International Airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico. It was humid and overcast, and an approaching storm made for a bumpy final descent. That day, a late-season tropical depression was forming over the Cayman Islands, dumping the heaviest rainfall the region had seen in years. Meteorologists had been modeling the storm for days and were now predicting that it could intensify into hurricane-force winds as it moved eastward toward Jamaica and Haiti.

Parrish was the senior vice president of corporate affairs at Philip Morris Companies, Inc., the world-famous cigarette company. More than four hundred Philip Morris employees who worked under him were due to arrive that day. Many had come from around the world, from as far as Switzerland and Romania and Hong Kong, to attend the companys periodic Corporate Affairs Worldwide Conference. The event was designed to train the companys global army of corporate affairs employees who plied a variety of trades, including talking with the news media, whispering in the ear of congressmen, and generally strategizing about how to feed the companys carefully crafted messaging to the world. While others on the tobacco side of the business were focused on the more mundane elements of selling cigarettesprocuring the tobacco from farmers, running the machinery that spit out thousands of cigarettes per minute, convincing store clerks to display Marlboros more prominently than Camelscorporate affairs employees during this high-stakes era were mercenaries engaged in political knife fights. Their militant posturing, and obsessive focus on containing unsavory facts about the companys products, turned what could have been a relatively transient policy disagreement or temporary misalignment between tobacco companies and the public into a long slog through the trenches of the Tobacco Wars.

For a decade, Parrish had been one of Philip Morriss key generals in waging that war. A son of a railroad worker from Moberly, Missouri, and a former trial attorney, Parrish had defended the tobacco industry in the landmark 1983 case involving the smoking-related illness of fifty-seven-year old housewife Rose Cipollone. The verdict in her favordelivered posthumously since she succumbed to her disease a year after filing the lawsuitmarked the first time that a tobacco company, despite facing hundreds of lawsuits up to that point, had ever suffered defeat in a product liability lawsuit. Even though the industry eventually won the case on appeal, it still was the canary in the coal mine for cigarette makersa tsunami of litigation was coming. Philip Morris, which had been a defendant in the case (although just one company, Liggett, was found to be liable), snapped up Parrish and named him corporate counsel. From there he quickly climbed to the highest rungs of the company.

Parrishs slight stature and voice kissed with a southern drawl belied a swagger that hed acquired as a trial lawyer, as well as his effortless abilityand willingnessto wield power. That combined with his calm, unassuming demeanor made him a wolf in sheeps clothing, exactly the trait that made him the perfect pick to lead corporate affairs through the tumultuous era.

He became the omnipresent face of Philip Morris through the companys darkest days. He was a key negotiator in tugs-of-war with a collection of stakeholders, including the Food and Drug Administration, multiple attorneys general, the White House, and scores of advocacy groups like the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. He spoke at press conferences, strategized behind closed doors, and was a constant fixture in the inner sanctum of Philip Morris executive meetings. He was a master at both Kissinger-style shuttle diplomacy and Machiavellian politicsthe two keys that guided Philip Morris through crisis after crisis. If Philip Morris in the latter half of the 1990s was a plane crashing, Parrish was the pilot that helped manage to land it, miraculously with not every passenger on board dying.

By then Philip Morris had grown into a conglomerate, with a menagerie of operating companies like Kraft and General Foods and Miller Brewing Company that sold a dizzying array of household staples: Lunchables, Jello-O, Miracle Whip, Velveeta, Miller Genuine Draft. The entire pantheon of Philip Morris brands, which had been cobbled together by the legendary dealmaker Hamish Maxwell, was lodged firmly in the zeitgeist of America. Not one, though, came close to being quite as indelible as Marlboro.

The advertising wizardry unleashed by the legendary adman Leo Burnett had transformed Marlboro in the 1950s from an underperforming cigarette for women into Americas number-one brand. With the help of twenty-five scientists, eight consulting firms, six independent labs, and one polling organization, Marlboro was relaunched in 1955 with a filter tip, a red-and-white flip top box, and a manly ad campaign featuring a Green Bay Packers player, a tattooed sailor, and of course, the square-jawed, salt-of-the-earth cowboy known as the Marlboro Man. Before long, Marlboro was the most popular cigarette brand around the world. Philip Morris had not only created one of the worlds most successful consumer brands of all time, it also birthed a Wall Street money machine that spit out lavish salaries for its executives and princely returns for its shareholders. The company would do whatever it took to protect its prize asset.

Parrish carried out his work in the spirit modeled by Philip Morriss then chief executive, Geoffrey Bible, a gregarious beer-drinking, chain-smoking Australian, whom a colleague once described as the Crocodile Dundee of the tobacco industry. Bible had a pit bulls instinct for a scrap. As product liability lawsuits mounted in the 1990s, Bible assured a group of investors not to get too worked upWe are not going to be anybodys punching bag, he told them. We shall fight, fight, and fight. To celebrate his leadership, his colleagues once presented him with a painting of a gyrfalcon, a bird of prey and the largest falcon on earth. Bibles bellicosity was enshrined in his trademark phrase repeated over the years in letters to customers, in speeches to employees, in presentations to investors: When you are right and you fight, you will win.