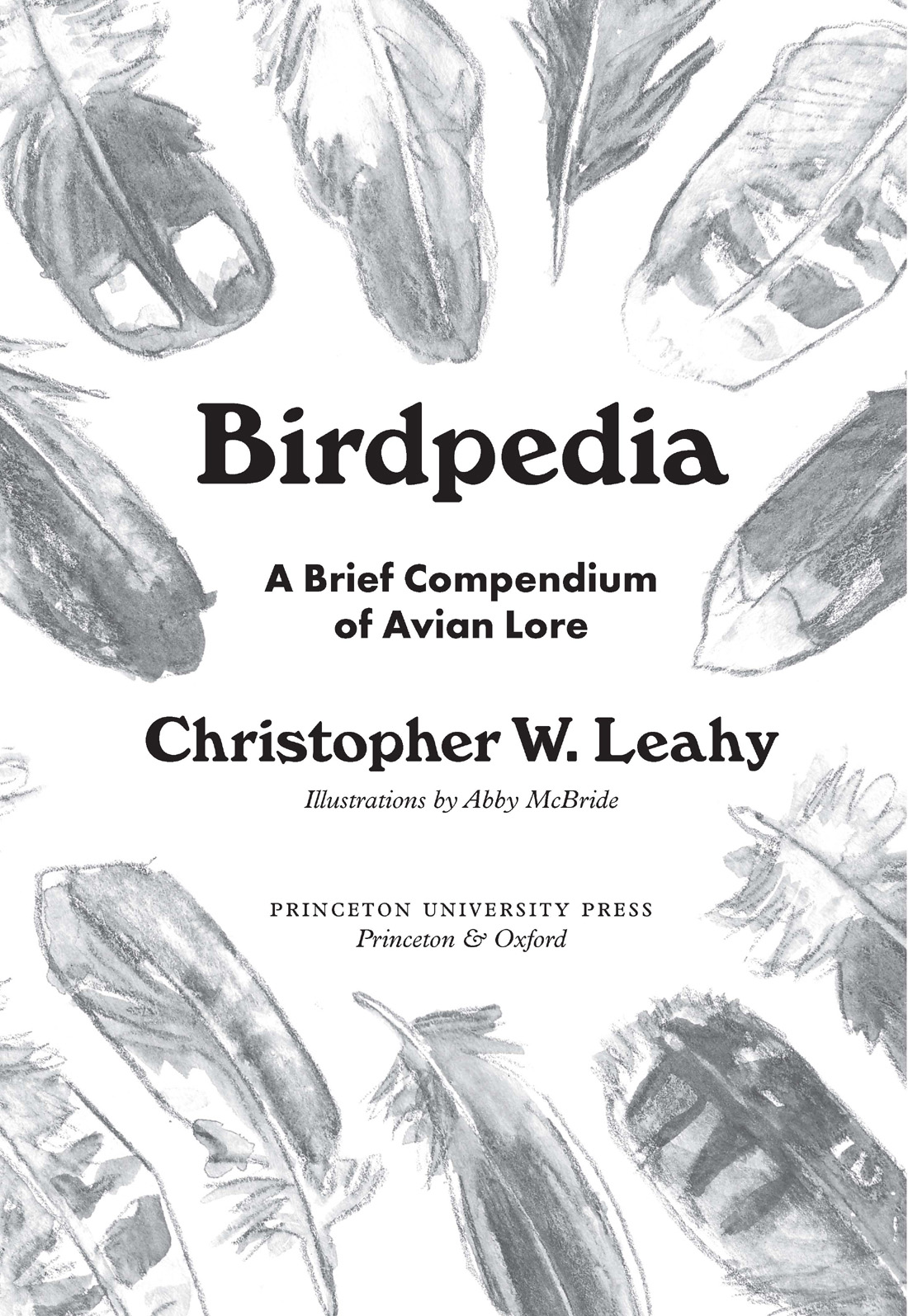

Birdpedia

Copyright 2021 by Christopher W. Leahy

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-20966-1

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-21823-6

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Robert Kirk and Abigail Johnson

Production Editorial: Mark Bellis

Text and Cover Design: Chris Ferrante

Production: Steve Sears

Publicity: Matthew Taylor and Kate Farquhar-Thomson

Copyeditor: Lucinda Treadwell

Cover, endpaper, and text illustrations by Abby McBride

This book has been composed in Plantin, Futura, and Windsor

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in China

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For James Bairdmentor, colleague, friend

Preface

Almost four decades ago, I published an encyclopedic handbook of North American birdlife titled The Birdwatchers Companion (Hill and Wang, 1982). At 917 pages, it fit comfortably under the definition of a tome. In 2002 Princeton University Press brought out a thoroughly revised and updated second edition that was even heftier, with a page count well over 1,000. My dualand perhaps somewhat duelingobjectives for the Companion were: (1) That it be comprehensive, encompassing a full gamut of ornithological knowledge, from what crepuscular means and who Alexander Wilson was to how many species of woodpeckers there are in the world and how to cook a scoter; and (2) That this potentially daunting accumulation of bird lore, while striving for meticulous accuracy, could also be written in an accessible style that could be read for pleasure as well as information even for fun.

Aside from a disparity in pure tonnage, the main difference between the Companion and the present modest volume is that the Birdpedia, while still composed of entries in alphabetical order, makes no claim to be encyclopedic. It might be described as a teaser perhaps, aiming ideally for the kind of curious reader who has noticed that a large and growing percentage of the worlds population has become fascinated in some cases obsessed! with birdwatching, or to use the sportier term, birding. If people now spend billions of dollars annually on optical equipment, identification guides, bird feeding paraphernalia, and guided tours to Mongolia in search of exotic species, it might be worth looking into a little book to find out why so many other wise sane people are staring into the trees or scanning smelly mudflats these days.

In the Birdpedia, you will find no exhaustive accounts of bird taxonomy or the avian digestive system or even descriptions of bird families. But there are general essays on Birdwatching and Identification that attempt to give the uninitiated a sense of what the fuss is all about; summaries of some of the more fascinating aspects of birdlife such as migration, brood parasitism, and vocal mimicry; as well as briefer, more whimsical entries calculated to provoke a smile or stretch credulity. The reader will still find a definition of crepuscular (not to mention goatsucker); still discover the identity of Alexander Wilson (not to mention Eleanora of Arborea); and still have access to scoter recipes. But the geographic coverage has been expanded beyond North America, and there is substantive material that did not appear in the Companion, such as Shakespeares Birds and Birding While Black.

There are birds everywhere. Swimming below the ice in Antarctica. Nesting by the millions on Arctic tundra. Dancing in the trees in the rain forests of Papua New Guinea. Gathering at oases in the Gobi Desert. Soaring over the highest peaks of the Andes and migrating above Mt. Everest. Chasing fish more than 1,750 feet down in the ocean depths. Sharing a meal with a pride of lions. Nesting on skyscrapers in New York City. And their distribution is by no means limited to geography. Birds are abundant in our art, in our poetry, in our music, in our myths and movies and medicine, in our food and fashions and fantasies. And in the fossil record millions of years before there were any human bones to ponder. It is this astonishing avian diversityof form, of behavior, of interaction with our own speciesthat the Birdpedia means to deploy to turn a nagging curiosity into a compelling fascination and perhaps a new, more intimate relationship with the natural world.

It can be said that a love of birds manifests itself in three fundamental ways: (1) as pure pleasurethe first Baltimore Oriole of the spring, the cry of a curlew over the marsh; (2) as an ever-widening curiosity that leads to newfound knowledge, perhaps even to wisdom; and (3) as a concern for the fate of the worlds birdlifenow gravely threatened by human recklessnessand a willingness to take action, however modest, to conserve it. My fondest hope for this modest volume of bird lore is that it might provide inspiration for all three.

Birdpedia

Red-billed Quelea

A bundance (How many birds?)

It should surprise no one that the question of how many individual birds are alive on this planet at any given moment has yet to be answered with any degree of certainty. True, there are a few highly conspicuous species, for example, Whooping Crane, whose breeding and wintering distributions have been fully discovered and whose total populations are so small that we know precisely how many individuals presently exist. But even estimates for scarce and well-studied species may have large error factors, either because it is difficult to distinguish individuals in populations of wide-ranging species, such as raptors, or because population numbers are extrapolated based on counts of singing males (e.g., most rare songbirds). The breeding populations of certain seabirds, for example, Laysan Albatross, Great Shearwater, Northern Gannet, and Roseate Tern, that nest locally in compact coloniesmost of which are knowncan be estimated with a high degree of accuracy simply by counting nest sites (though these counts do not include pre-breeding or vacationing birds). But when we consider even so limited a goal as calculating the number of Black-capped Chickadees in Massachusetts during a given monthnot to mention the number of songbirds in India or the planets total avian populationwe begin to appreciate the difficulty of the task. To begin with, simply counting accurately the number of small woodland birds in a 10-acre plot involves much patience and labor and leaves the counter with little confidence that absolute accuracy has been achieved. Once there are reasonably reliable counts for a range of species and habitats, one can begin to make some tentative extrapolationsbut consider some of the variables involved:

Next page