Also by Larry Writer from Pier 9

The Australian Book of True Crime

The Australian Book of Heroism

Sunshine and Shadow (with James and Stephen Dack)

Published in Australia in 2011 by Pier 9, an imprint of Murdoch Books Pty Limited

Murdoch Books Australia

Pier 8/9

23 Hickson Road

Millers Point NSW 2000

Phone: +61 (0) 2 8220 2000

Fax: +61 (0) 2 8220 2558

www.murdochbooks.com.au

Murdoch Books UK Limited

Erico House, 6th Floor

93-99 Upper Richmond Road

Putney, London SW15 2TG

Phone: +44 (0) 20 8785 5995

Fax: +44 (0) 20 8785 5985

www.murdochbooks.co.uk

For corporate orders and custom publishing contact Noel Hammond,

National Business Development Manager

Publishing Director: Chris Rennie

Editor: Tricia Dearborn

Production: Renee Melbourne

Text Larry Writer 2011

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Cover design Murdoch Books Pty Limited 2011

Cover photography by Jonathan Wood/Getty Images

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Writer, Larry

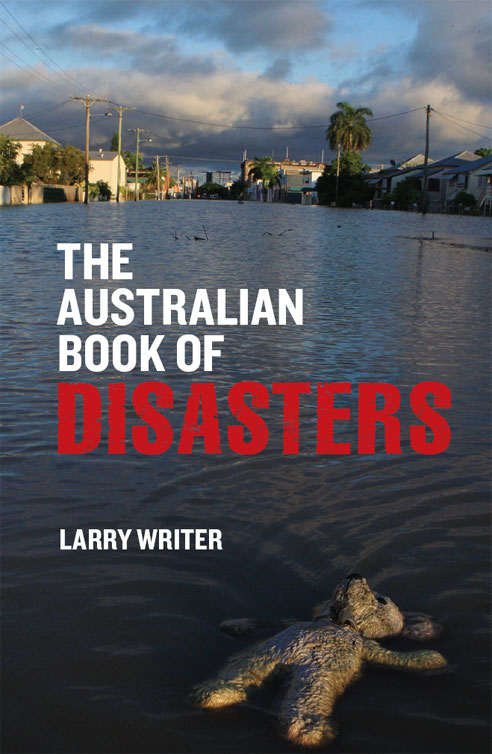

Title: The Australian book of disasters [electronic resource]/ Larry Writer

ISBN: 9781742664668 (eBook.)

Notes: Includes Index

Subjects: Natural disastersAustralia

Dewey Number: 363.340994

For all those who find themselves in

the eye of the storm

Contents

PREFACE

A ustralia is a land richly blessed. Yet it seems fate and the elements perversely balance our blessings by periodically inflicting disasters on this wide brown land. The word disaster derives from the Greek dus and aster meaning bad star and is defined as an event that causes major destruction and damage, loss of life and significant change to the built or natural environment. Bushfires, drought, floods, earthquakes, cyclones, epidemics, plane, train and vehicle crashes, shipwrecks and explosions have always been part of our history. And because these disasters which are usually unpreventable strike anywhere at any time, and impact terribly on the lives of everyday innocent people, they elicit from the nation deep grief and sorrow.

This book chronicles a number of natural and man-made disasters that have befallen Australia. It is not comprehensive any attempt to make it so would result in a publication thousands of pages long. Rather, it focuses on a variety of disasters that have beset us over the past century or more in various parts of the nation. The very names by which they have come to be known evoke shudders in the national consciousness: the Queensland floods; Cyclone Tracy; the Granville train disaster; the Black Saturday bushfires; the wreck of the Dunbar; the Christmas Island asylum seeker tragedy; the Spanish Flu pandemic; the Newcastle earthquake. These are all recounted in this book, as well as lesser known, but to those who suffered in them equally dreadful calamities.

Though each disaster is inimitable, common threads run through every story: courage, sacrifice, kindness, faith in ones fellows. Disasters apply a blowtorch to the souls of those caught in their eye and the great majority of people, when put under unimaginable pressure, respond bravely, resourcefully and coolly. The Australian Book of Disasters bursts with heroes. Some people, of course the looters and profiteers react less admirably. Yet in the end, this book, while documenting calamitous events, is an attempt to celebrate the resilience of the human spirit in dire times, as well as the enduring ability of Australians to pick themselves up after being knocked down, and press on.

CHAPTER 1

THE WRECK OF THE DUNBAR

20 August 1857

N earing midnight on 20 August 1857, while being buffeted by a tumultuous storm with gale-force winds, torrential rain and lightning strikes, the passenger ship Dunbar smashed into cliffs on Sydneys South Head. The ship sank, and 122 passengers and crew of its total complement of 123 perished: drowned, torn to pieces by razor-sharp rocks, or mauled by sharks. When it foundered, the Dunbar was in the final hours of an eighty-one-day voyage from Plymouth, England, and just 12 nautical miles from Circular Quay and safety.

The Dunbar was just north-east of Sydney Heads when it ran head-on into the storm, which was roaring up the coast from the south-east. Squalls and gale force winds whipped the waves into liquid mountains. The storm was so severe that the spray from the cliffs shot straight up into the air scores of metres higher than the towering cliff tops. The same front of bad weather flooded the Hawkesbury region.

Despite the terrible conditions, the Dunbars captain, James Green, a vastly experienced sailor and skipper, made the decision to enter the Heads, keeping the Macquarie Light on the Dunbars port bow. There was a terrified cry from a lookout: Breakers ahead! Green was disorientated and came to believe his ship was making for North Head. He ordered the helmsman to swing the ship hard to port. It was a death sentence, as the Dunbar was flung broadside into the cliffs. The wooden vessel splintered, the mizzen and main masts fell, the lifeboats were staved in, and the vessel capsized onto its side as the monstrous waves crashed down upon it. One sailor, deckhand James Johnson, was thrown overboard and ended up on the rocks. He clambered up the cliff face to escape the pounding seas and passed out on a ledge halfway up the 50-metre cliff. Johnson was the sole survivor.

The Dunbar was a 1186-tonne, oak and teak, three-masted clipper. She was commissioned in 1854 and built by James Laing and Son at Sunderland, England. Construction took eighteen months and cost more than 30,000. It was the time of the great Australian gold rush, and the Dunbars mission was to transport gold-seeking passengers, and other travellers, between London and Sydney. But before sailing to Australia, she was press-ganged into service conveying British troops to the Crimean War. It wasnt until 1856 that she made her maiden voyage to the southern hemisphere. She was not just one of the worlds biggest merchant ships, but in common with the similarly doomed Titanic, which went down in 1912 one of the fastest and most luxurious. The first-class section was always packed. On board on her fatal, second, voyage from England to Australia was more than 72,000 worth of livestock, machinery, furniture, cutlery and other expensive goods.

The disaster profoundly undermined the thriving colonys confidence. Journeying to England was a popular pastime, undertaken virtually without a qualm. The demise of the Dunbar, a state-of-the-art vessel with every modern convenience and safety device, emphasised in the most telling manner that Australia was an isolated and vulnerable country, and that sea travel was always fraught with danger. (This fact was further brought home to the reeling colony when nine weeks after the Dunbar sank, the timber barque