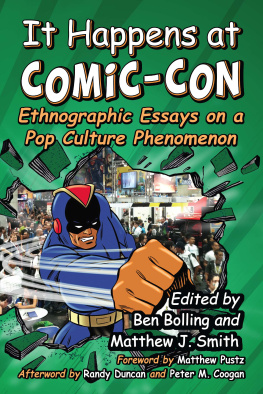

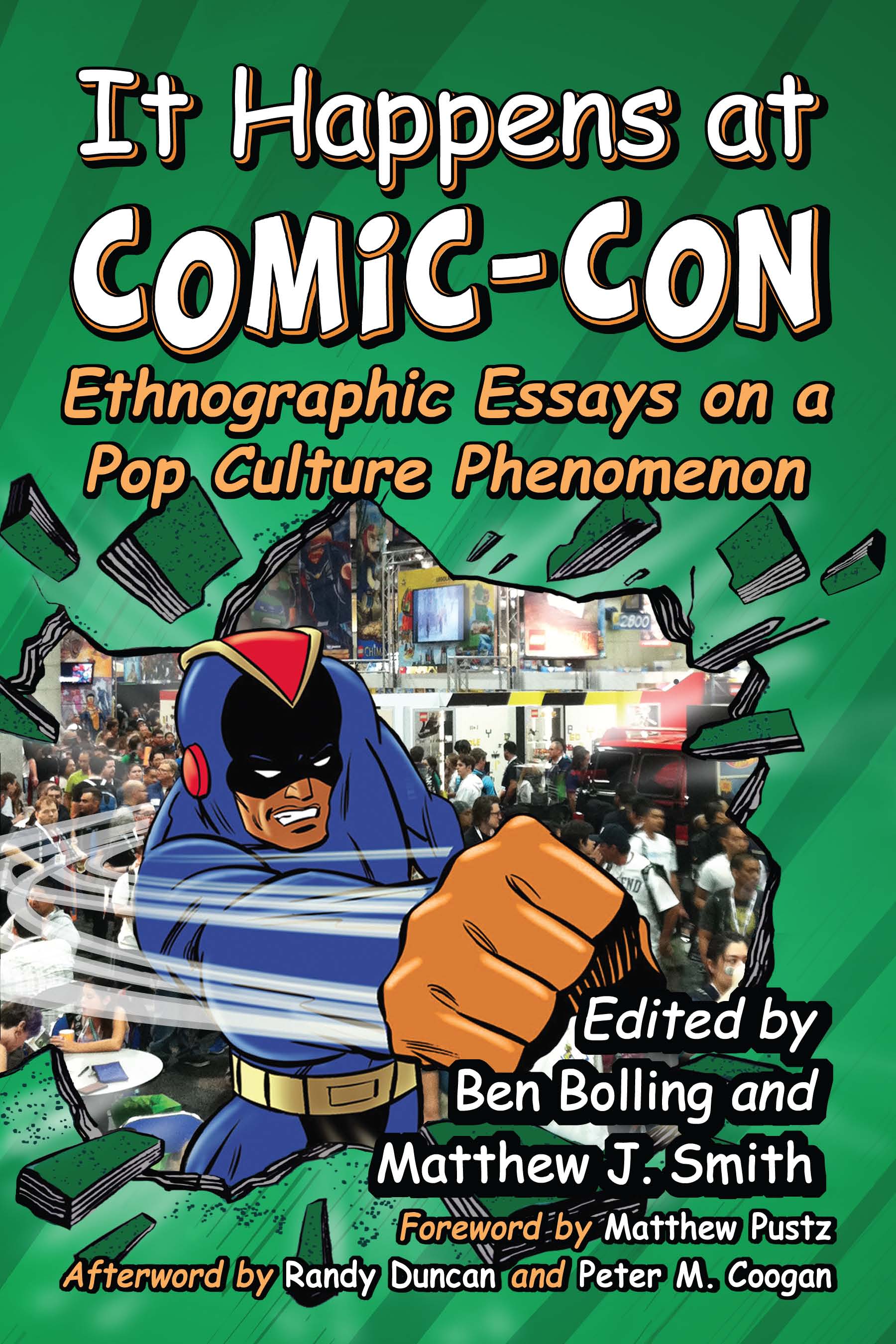

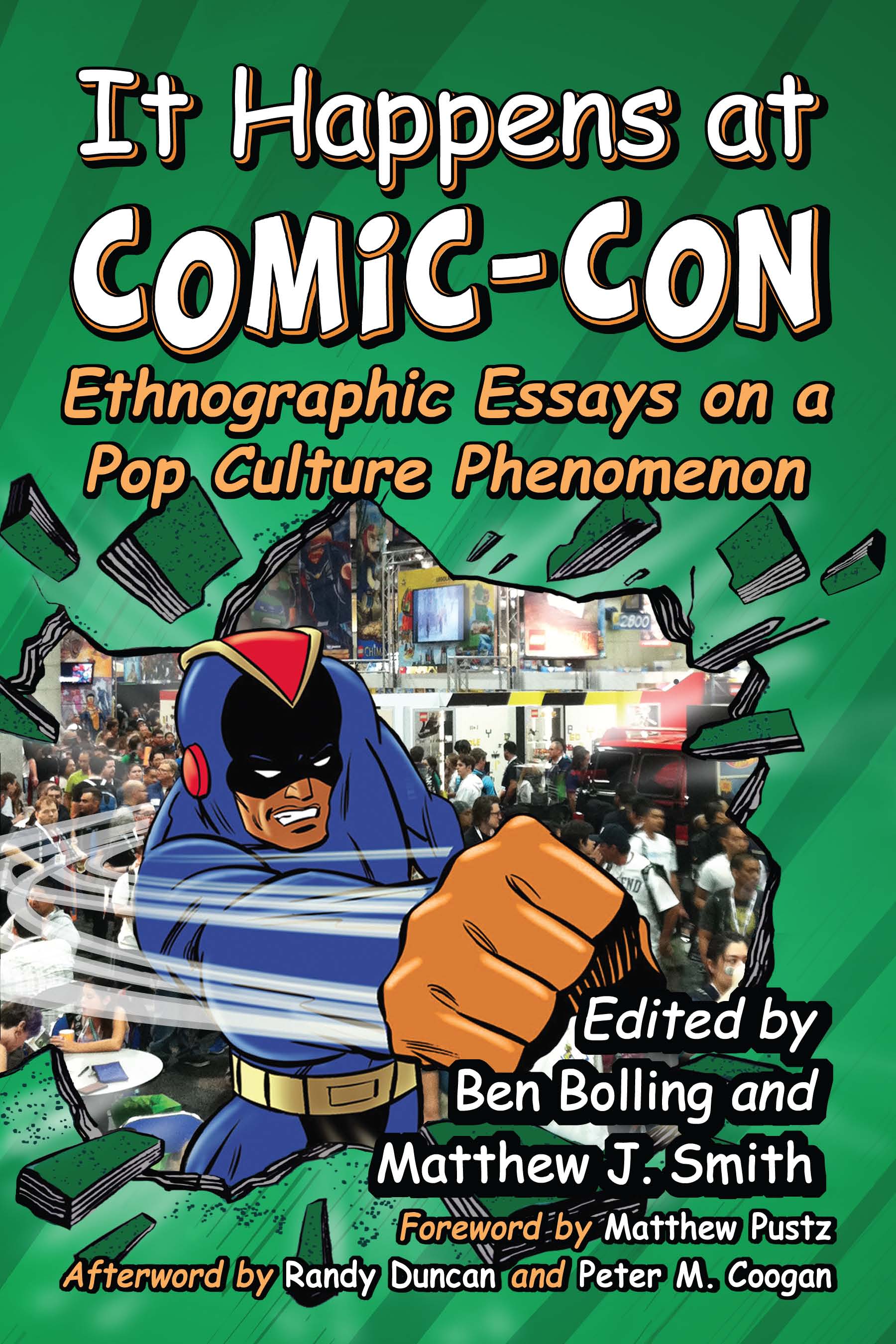

It Happens at

Comic-Con

Ethnographic Essays on a Pop Culture Phenomenon

Edited by Ben Bolling and Matthew J. Smith

Foreword by Matthew Pustz

Afterword by Randy Duncan and Peter M. Coogan

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1447-2

2014 Ben Bolling and Matthew J. Smith. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: super hero punching wall ( 2013 Digitalvision); Comic-Con 2013 (Layla Milholen)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To my parents for fostering a lifeling love of comics, to Jon for getting me to CCI each summer, and to Matthew J. Smith for guiding us all through the endlessly fascinating world of the Con.

Ben Bolling

To Randy Duncan, Peter M. Coogan, Kathleen McClancy, and Travis Langley with gratitude for opening the doors of Comic-Con to student-scholars.

Matthew J. Smith

Foreword

Visiting Comic-Con, Revisiting Comic Book Culture

MATTHEW PUSTZ

When I got off the trolley in downtown San Diego, I knew just how to find it: follow the guy in the Green Lantern t-shirt. After a short walk, there it wasComic-Con International, with the huge convention center sitting in the sun. Waiting to enter were tens of thousands of fansall with their own strategies for making the most of what has become one of the largest popular culture events in the world. This was the summer of 2007, and I had traveled to San Diego all the way from Boston to attend something that I had dreamed about for a long time. I had attended comic book conventions before, in Chicago, Columbus, Ohio, and St. Louis. But San Diego was different, bigger, more important. This was San Diegothe Super Bowl of comic book conventionsand I was on the comic book fans holy pilgrimage, the trip that all fans must make at least once in their lives. This was the Gathering of the Nerd Tribes, Fanboy Woodstock. This was BIG, and I was thereas a professional, no less.

I was attending Comic-Con International because of the efforts of one man, Matthew Smith. It was always a possibility before, I suppose, but I never felt ready to battle the crowds, rush for a hotel room, or save up the money that it would take to experience San Diego. As a poor graduate student, community college professor, and finally adjunct instructor, I never felt like I could justify the expense. Writing my dissertation on comic books and the people who read them, I know I should have gone, but teaching stipends only go so far. Attending smaller conventions where I could stay with family or friends seemed like a better alternative. But when I got to San Diego, I saw that I was wrong, that Comic-Con is so much bigger and so much more intense than anything I had attended before that there really was no comparison. If I really wanted to study comic book cultureas the title of my book suggestedthen San Diego was the place where I had to go.

Professor Smith realized this, which is why he began to bring students to the convention. He understood that Comic-Con was the perfect site for popular culture ethnography, a place where students could become the ultimate participant-observers by focusing on the intersection of fan cultures in San Diego. Not only would his students find comic book culture but they would also discover fans of science fiction, video games, horror films, Japanese anime, cult movies, British television, and much, much more. And perhaps most important, Professor Smiths students would quickly come to understand that these fan cultures were interconnected not only with each other but also with the forces of production, marketing, and distribution. Comic-Con is a fan event, but its also a money-making extravaganza where all manner of creators, artists, and corporate owners of media products can sell and promote them to their exact target market. And this target market is one that can be virtually guaranteed to take the buzz of Comic-Con back with them to Iowa or Boston or Tokyo so they can sell those products to their friends back home. Comic-Con is the ultimate merging of culture and commerce, and that makes it the perfect place to study how popular culture works in the twenty-first century.

The students that Professor Smith brings to Comic-Con needed a textbook, and I was lucky enough to have written the first real academic analysis of comic book fandom. Published in 2000 by the University Press of Mississippi, Comic Book Culture: Fanboys and True Believers is the book version of my dissertation. I earned my Ph.D. in 1998 and the book was published less than a year and a half later. As with most dissertations, my thesis was the product of literally years of work and I was proud of what I had produced. Some of the strongest parts of the book illustrated some important truths about the culture of comic book fans in the United States. Comic book fans, I wrote, constituted a unique and fully realized culture, with its own values, standards, beliefs, rituals, and mythology. This culture was created in part through the comic books themselves which had increasingly become self-referential as publishers marketed them to people who had identified themselves as fans. These devoted readers had even developed a sense of comic book literacy which helped to separate fans from outsiders. For Professor Smiths students, then, Comic Book Culture was (and continues to be) a guidebook and a framework.

These students are not just using my book as the cornerstone of their Comic-Con experience. They are also keeping my book alive. Academics often talk about wanting their projects to be the start of something rather than an intellectual dead-end. We often talk about wanting other scholars to build off of our work. Seeing Professor Smiths students doing just that with Comic Book Culture is a huge thrill. This might sound like a clich, but its actually true, and I would like to publicly thank them for that here.

An awful lot has changed since Comic Book Culture was first published in 2000. Perhaps most importantly, a new sense of respect for comics has emerged in the United States. We are in an era in which it is normal for comic books to be considered literature. Yes, newspapers and magazines continue to publish articles that breathlessly announce that comics are not just for kids anymore while still featuring sound effects in their headlines. For the most part, though, there is an awareness in newspaper book review sections and mainstream magazines now that comic books can be literature. Graphic novels like David Mazzucchellis Asterios Polyp, Chris Wares Building Stories, and Charles Burns Black Hole have been as widely praised as any traditional novels during the last decade. Commentators from a wide variety of media outlets have loved autobiographical comics like Alison Bechdels Fun Home and Marjane Satrapis Persepolis, and they have not been shy about letting the public know. There are now even anthologies that provide annual compilations of the best comics of the year. Serious, literary, challenging comics are more visible than they ever have been. A big part of the reason for this is the presence of sections in bookstores dedicated to Graphic Novels. Many comics scholars wince at this label being applied to everything from Spawn trade paperbacks to Robert Crumbs adaptation of Genesis, but its hard to deny that having their own section in Barnes & Noble and independent bookstores has helped to increase the level of mainstream cultural acceptance for comics.

Next page