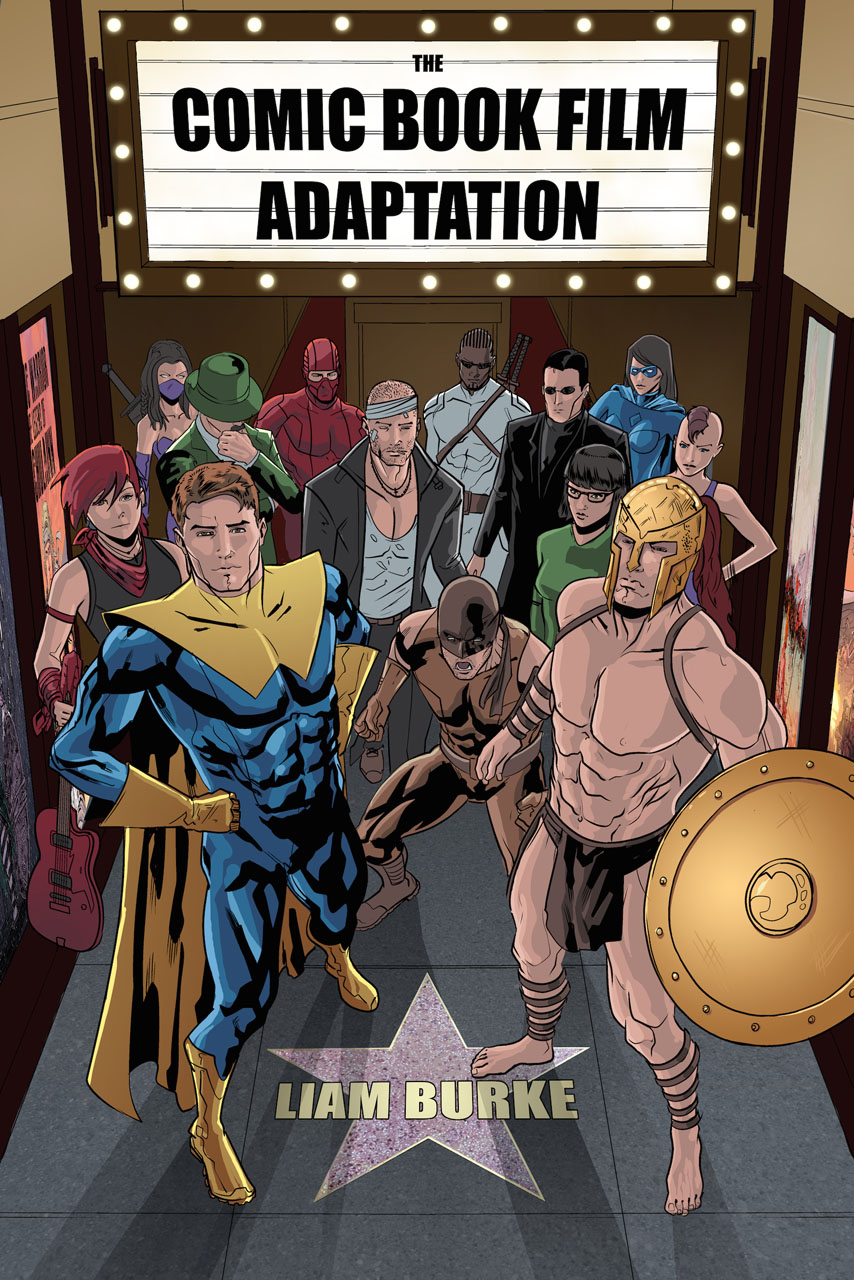

THE COMIC BOOK FILM ADAPTATION

THE COMIC BOOK FILM ADAPTATION

Exploring Modern Hollywoods Leading Genre

LIAM BURKE

University Press of Mississippi / Jackson

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2015 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2015

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burke, Liam (Liam P.)

The comic book film adaptation : exploring modern

Hollywoods leading genre / Liam Burke.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62846-203-6 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-62674-515-5 (ebook)

1. Film adaptationsHistory and criticism. 2. Motion pictures and comic books. 3. Superhero films. 4. Comic strip characters in motion pictures. 5. Motion picture production and directionUnited States. 6. Motion picture industryUnited States. I. Title.

PN1997.85B87 2015

791.436dc23 2014042191

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With many solitary evenings spent pursuing an ever-receding goal, there are more than a few parallels between researching a book and the exploits of comic book loners. However, in compiling these acknowledgments I was reminded of the heros epiphany in the final panels of Grant Morrisons The Return of Bruce Wayne, The first truth of Batman I was never alone. I had help. I would like to recognize the contributions of the many groups and individuals who guided this book to publication.

Firstly, I want to thank Leila Salisbury and the team at the University Press of Mississippi for taking on this project, and all the care and patience they demonstrated. Much of this research was carried out during my time at the Huston School of Film & Digital Media at the National University of Ireland, Galway, and I would like to acknowledge my former colleagues Sen Crosson, Sean Ryder, Tony Tracy, Dee Quinn, Conn Holohan, and Rod Stoneman for their advice and support. Equally, I must recognize my colleagues at Swinburne University of Technology, in particular Carolyn Beasley for her diligent proofreading and Jason Bainbridge for applying the keen eye of a fan and a scholar. I was fortunate to be funded by the Irish Research Council during the earliest stages of this research, support for which I am very grateful.

I would like to thank the industry professionals who took the time to discuss their work, including Evan Goldberg, Kevin Grevioux, Joe Kelly, Paul Levitz, Steve Niles, Dennis ONeil, Scott Mitchell Rosenberg, Michael E. Uslan, and Mark Waid. These interviews provided insights that greatly enriched this study. Special thanks must go to Will Sliney, whose dynamic cover leaves little doubt as to why he is quickly becoming one of Marvel Comics most popular artists.

Over the course of my research, this book has consistently been reworked. Much of this refinement can be attributed to the scholars I have met on the long road to publication. Firstly, I would like to thank Will Brooker for his detailed feedback and guidance. I want to recognize Peter Coogan, Randy Duncan, and Kathleen McClancy of the Comics Arts Conference, and Imelda Whelehan and Deborah Cartmell of the Association of Adaptation Studies for the many opportunities to present my research and receive crucial advice. I would also like to thank Martin Barker for important pointers, as well as the opportunity to publish early findings in Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies. Furthermore, I must acknowledge the anonymous readers who provided essential feedback.

A sincere thank-you to Neasa Glynn and the staff of the Eye Cinema, Galway, for allowing me to carry out important audience research, as well as the many filmgoers who graciously filled out surveys. I would like to acknowledge my friends who lent their support and expertise. From helping out with surveys to proofreading drafts, I am indebted to Dave Coyne, Veronica Johnson, Gar OBrien, Siobhan OGorman, Barry Ryan, Adam Scott, and Maura Stewart. Graph-Man Andrew Rea deserves particular credit for his enthusiasm and essential design skills. I would, of course, like to thank my family for their unwavering encouragement. Finally, and most importantly, I need to express my heartfelt appreciation to my wife, Helen, who has endured too many hours of comics and films, incalculable dog-eared drafts, and holidays annexed by conferences. Her support is unconditional, and it is to Helen that I dedicate this book.

THE COMIC BOOK FILM ADAPTATION

INTRODUCTION

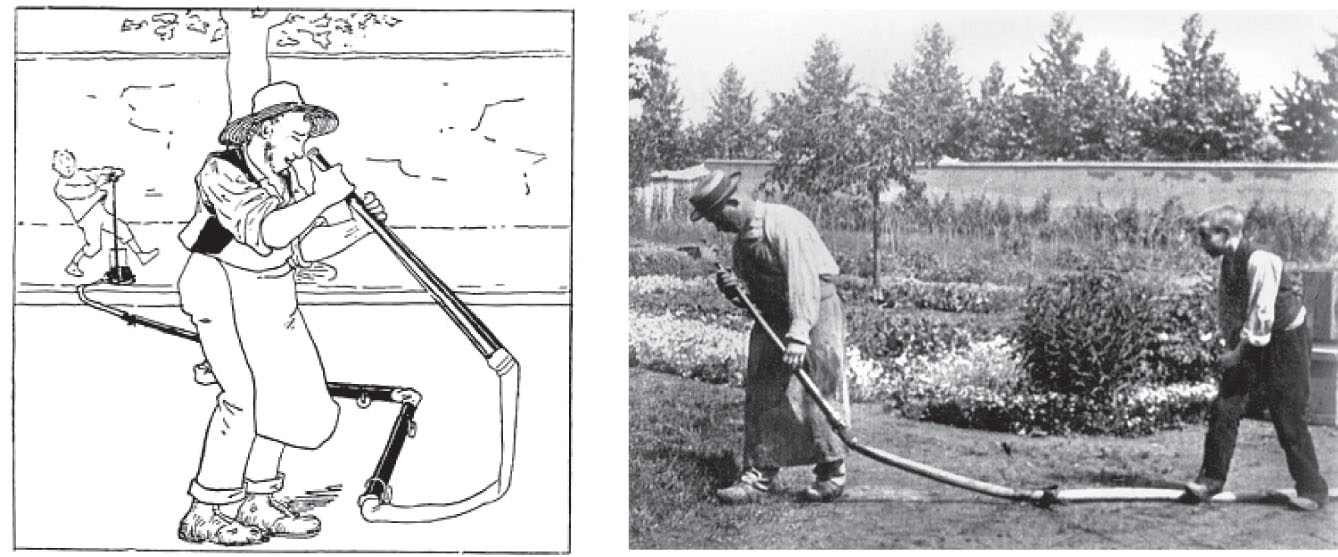

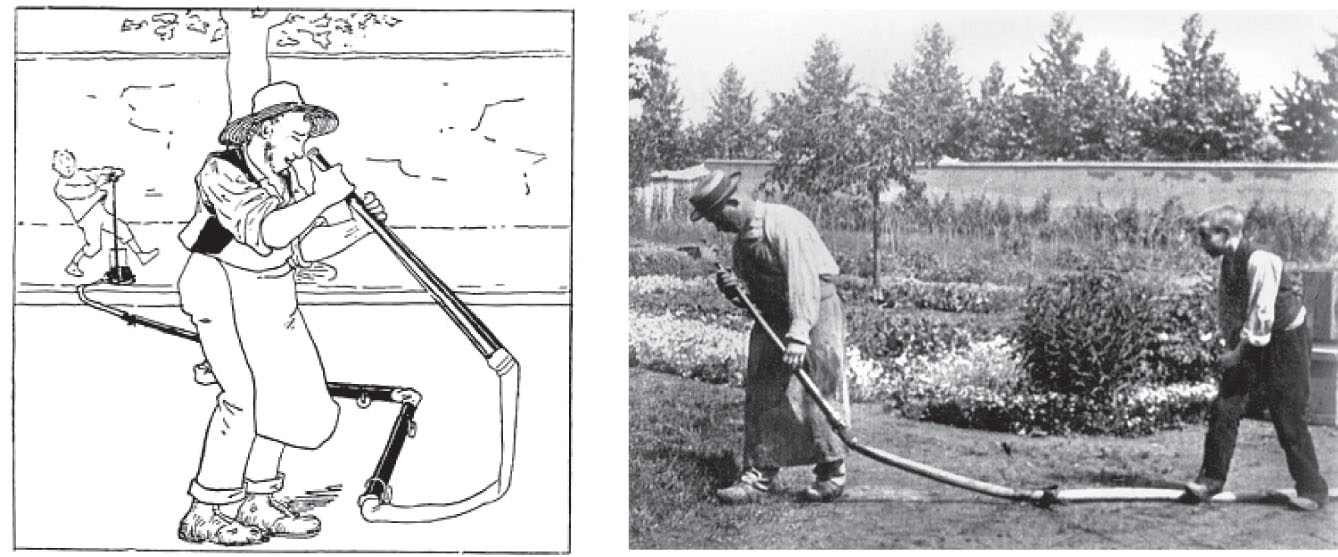

A gardener is innocently watering flowers when a mischievous young boy steps on the hose. When the man inspects the nozzle, the boy releases the flow, soaking him. Not to be outdone, the gardener catches the boy, and, after ensuring they are both in frame, reprimands him with a few vigorous slaps across the backside. This is the basic, but effective, setup of Louis Lumires LArroseur Arros (1895). The staged comedy, a novelty in an era of slice-of-life actualits, is often celebrated as the first narrative film. However, what is often overlooked is that LArroseur Arros is also cinemas first adaptation of a comic.

Throughout the early days of cinema, this emerging entertainment looked to other media to confer artistic credibility and narrative stability. Although novels and plays were the most adapted materials, films based on comics maintained an important presence. Georges Sadoul argues that LArroseur Arros borrowed its premise from a nine-image comic, LArroseur, by artist Hermann Vogle (1887), while Lance Rickman identifies variants on this gag in a number of comics in the years leading up to Lumires innovation. Today, it is impossible to ignore cinemas heavy reliance on comics. From superheroes to Spartan warriors, comics have moved from the fringes of pop culture to the center of mainstream film production.

FIG. I.1 A panel from Un Arroseur Public (A Public Waterer) by Christophe (3 August 1889), one of the many widely available comics that used the waterer premise in the years before cinemas first narrative film LArroseur Arros (Lumire 1895).

Prior to this modern trend, comic book adaptations received little attention from scholars publishing in the English language. Nonetheless, even with the high number of films produced since 2000, this area remains relatively underexplored. Most analyses appear as contributions to anthologies (e.g., Brooker Batman; Ecke; Loucks), journal articles (Becker; Ioannidou; Jones), or as chapters in monographs meeting wider remits (Lichtenfeld, Bukatman Poetics of Slumberland), with the collection Film and Comic Books edited by Ian Gordon, Mark Jancovich, and Matthew P. McAllister perhaps the only dedicated book.

Comics scholars are among those that one might expect to give this area sustained academic attention. Yet, motivated by a desire to maintain the boundaries of their nascent field, these academics have largely ignored the topic, with Greg M. Smith explaining: Dealing with comics alone is hard enough without compounding the difficulty by studying two different objects (Studying Comics 111). Similarly, adaptations studies, which recently widened its view beyond the novel-to-film debate, has only made tentative steps in this area, with Thomas Leitch suggesting this reluctance may stem from a belief that adapting texts that are largely visual to begin with seems so easy, simple, or natural that the process has limited theoretical interest (

Next page