WHEN TECHNOCULTURES COLLIDE

Cultural Studies Series

Cultural Studies is the multi- and inter-disciplinary study of culture, defined anthropologically as a way of life, performatively as symbolic practice, and ideologically as the collective product of varied media and cultural industries. Although Cultural Studies is a relative newcomer to the humanities and social sciences, in less than half a century it has taken interdisciplinary scholarship to a new level of sophistication, reinvigorating the liberal arts curriculum with new theories, topics, and forms of intellectual partnership.

Wilfrid Laurier University Press invites submissions of manuscripts concerned with critical discussions on power relations concerning gender, class, sexual preference, ethnicity, and other macro and micro sites of political struggle.

For more information, please contact:

Lisa Quinn

Acquisitions Editor

Wilfrid Laurier University Press

75 University Avenue West

Waterloo, ON N2L 3C5

Canada

Phone: 519-884-0710 ext. 2843

Fax: 519-725-1399

Email:

WHEN TECHNOCULTURES COLLIDE

Innovation from Below

and the

Struggle for Autonomy

Gary Genosko

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Wilfrid Laurier University Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

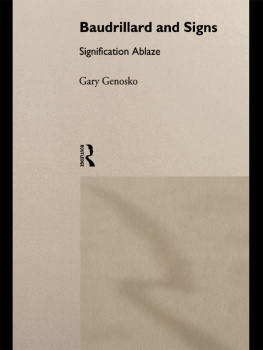

Genosko, Gary, 1959, author

When technocultures collide : innovation from below and the struggle for autonomy / Gary Genosko.

(Cultural studies series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55458-897-8 (bound).ISBN 978-1-55458-899-2

(epub).ISBN 978-1-55458-898-5 (pdf)

1. TechnologySocial aspects. 2. Technological innovationsSocial aspects. 3. Technology and civilization. I. Title. II. Series: Cultural studies series (Waterloo, Ont.)

T14.5.G48 2013 306.46 C2013-903854-X C2013-903855-8

Cover design by Blakeley Words+Pictures. Front-cover photo: Anonymous, by Declan Roache. Reproduced with permission of the photographer. Text design by James Leahy.

2013 Wilfrid Laurier University Press

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

www.wlupress.wlu.ca

This book is printed on FSC recycled paper and is certified Ecologo. It is made from 100% post-consumer fibre, processed chlorine free, and manufactured using biogas energy.

Printed in Canada

Every reasonable effort has been made to acquire permission for copyright material used in this text, and to acknowledge all such indebtedness accurately. Any errors and omissions called to the publishers attention will be corrected in future printings.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit http://www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

For Hannah and Iloe, my crafty daughters

Contents

Acknowledgements

O ver the course of the ten years that I ran the Technoculture Lab, I was fortunate to have a number of very talented graduate students who assisted me in several of the projects that appear as chapters in this book. I am indebted to the work of Scott Thompson (creator of the tables) during the period when I was writing about Mafiaboy, and to Andriko Lozowy, who helped me first define the issues around Crack-Berry abuse and really drill down theoretically into failure.

During his regular visits to the Lab, Paul Hegarty worked with me on redirecting concepts from Bataille and Baudrillard towards info-tech objects and systems, especially the big toe as a way of productive disabling. Our Bletchley Park scavenger hunt was a catalyst (http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=613). I am also grateful to Roberta Buiani with whom I collaborated on a postdoctoral project concerning Italian Yippies (for the journal Cultural Studies). Working on a book, and making a film with Franco Bifo Berardi (After the Future), proved to be transformative for my thinking about the direction in which technoculture is headed, and about the fuzzy destinies of post-autonomist thought and practice. Greg Elmer, Ganaele Langlois, and Alessandra Renzi at the Infoscape Lab at Ryerson University were especially generous with their support during Bifos visits to Toronto. I first aired my electrical dreams of utility hacks there. The participants in my WikiLeaks graduate seminar enthusiastically embraced the challenge of trying to make sense of a developing story and to analyze whistle-blowing. I will be revisiting the latest instalments of the WikiLeaks saga in a further seminar as it undertakes some of the tasks the US government once promised it would address. Information, like electricity, wants to be free.

Much of the research for this book was made possible by the Canada Research Chairs and Canada Foundation for Innovation programs. The final stages of the manuscript were prepared and corrected at UOIT.

Introduction

T echnoculture appears to be a relatively recent coinage dating from the 1960s. In its blandest deployment, it simply makes note of the mutual influences of technology and culture, often drawing on one or more media to establish points of contact. Writing within the sweeping parameters of medium theory, American neologist Henry G. Burger wrote in a letter to the editor of the journal Technology and Culture that it was the availability of cheap Bibles (hence print), not to mention demand for them, that suggested to him the need for a new area of study that names the mutually supportive dimensions of technology and culture: I propose the discipline be named technoculture (1961: 261).

Far from constituting a new discipline or even sub-area, technoculture quickly became associated with technocratic ideology in which technology dominates cultural formations, via shifts in social organization, and determines their possibilities. It seems that the descriptive interdependence thesis, which is still in circulation today, and the technocratic hypothesis, also still much in evidence in the critical literature, together continue to influence the approaches available in technoculture studies.

The interdependence thesis is expressed by Debra Benita Shaw (2008: 4) as an enquiry into the relationship between technology and culture and the expression of that relationship in patterns of social life, economic structures, politics, art, literature It is also a quintessentially post-modern study in that it is a reflexive analysis from within, as it were, the belly of a beast that has grown to monstrous proportions. Word processing and publishing about technoculture within the belly of the technocultural beast requires reflexive awareness in the description of technocultures expressive features in social and political life and how this very thesis is generated, relayed, and reproduced. Shaw is very clear on this point. The relative clarity of the grammar of this thesisthat a relationship exists between technology and culture the expressions of which are observable and describablehas also been troubled by critics for whom the postmodern and reflexive do not vouchsafe such ease of access. Sadie Plant (1997: 4546), in her contribution to the discussion, points out that in both the study of culture and technology the former cannot be determined by a single coherent factor and the latter exerts a power that is riddled at all scales by turbulence and uncertainty; hence, whatever it is that is called technoculture is unstable and its interdependency difficult to access and to assess. Description is not so easy. There is a certain degree of convolution between culture and technology and a lack of givenness in the foliations.

Next page