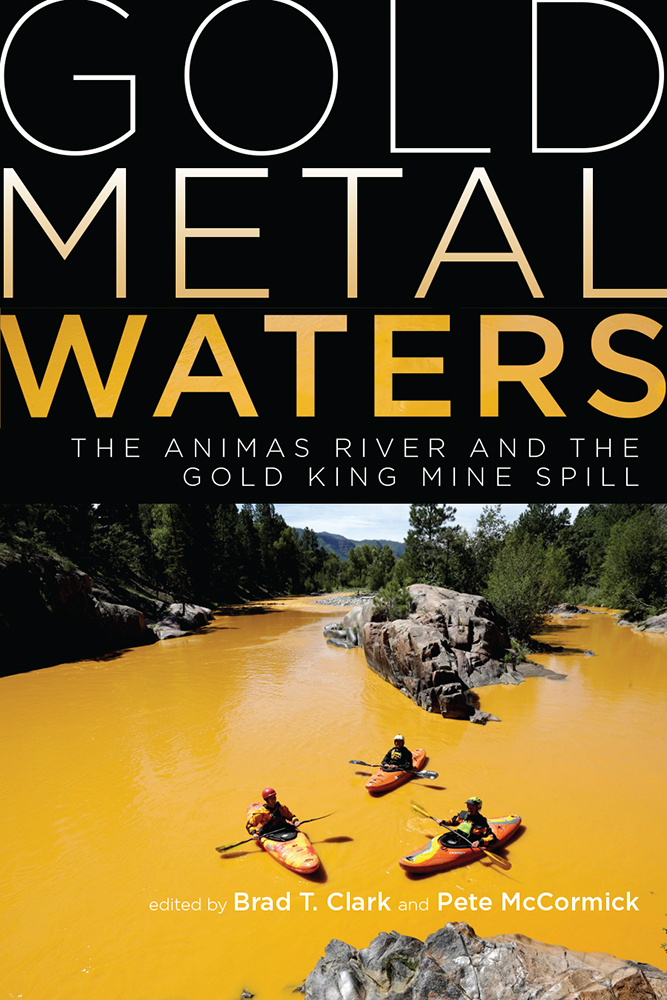

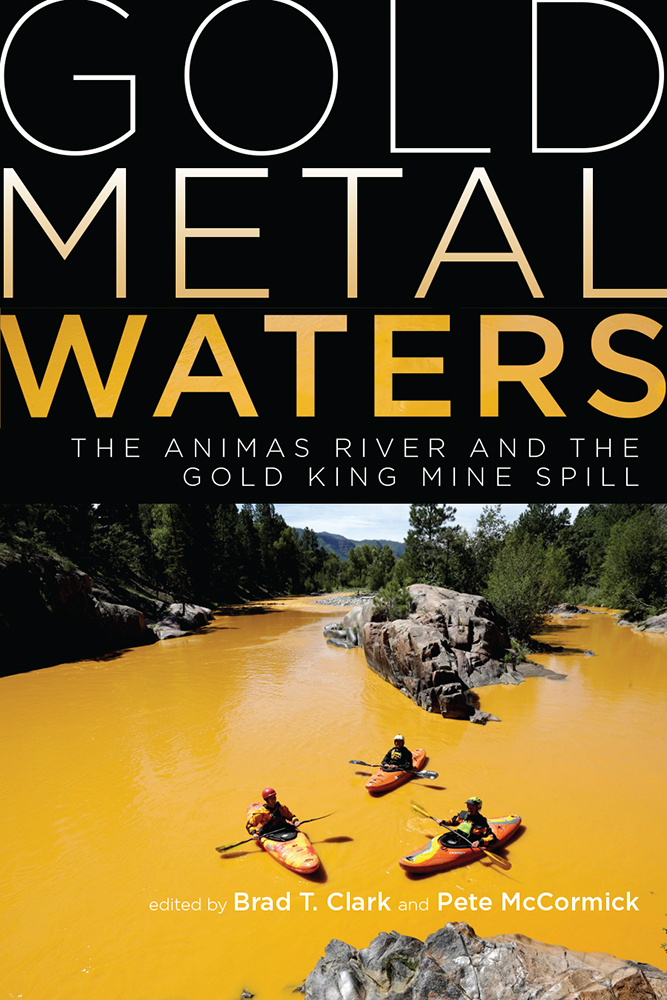

Gold Metal Waters

The Animas River and the Gold King Mine Spill

EDITED BY

Brad T. Clark and Pete McCormick

U NIVERSITY P RESS OF C OLORADO

Louisville

2021 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

245 Century Circle, Suite 202

Louisville, Colorado 80027

All rights reserved

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of Wyoming, Utah State University, and Western Colorado University.

ISBN: 978-1-64642-174-9 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-1-64642-175-6 (ebook)

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781646421756

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Clark, Brad T., editor. | McCormick, Pete, 1971 editor.

Title: Gold metal waters : the Animas River and the Gold King Mine spill / edited by Brad T. Clark and Pete McCormick.

Description: Louisville : University Press of Colorado, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021001160 (print) | LCCN 2021001161 (ebook) | ISBN 9781646421749 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781646421756 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Acid mine drainageColoradoGold King Mine (San Juan County) | Abandoned mined lands reclamationAccidentsColoradoGold King Mine (San Juan County) | Waste spillsColoradoGold King Mine (San Juan County) | WaterPollutionAnimas River (Colo. and N.M.) | Hard rock mines and miningEnvironmental aspectsWest (U.S.)

Classification: LCC TD427.A28 G65 2021 (print) | LCC TD427.A28 (ebook) | DDC 363.17/90978829dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001160

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001161

Front-cover photograph: Jerry McBride/Durango Herald/Polaris. Back-cover illustration: courtesy, Center of Southwest Studies, Fort Lewis College, Durango, Colorado.

For the people of the Animas Basin who have shown remarkable resilience, time and time again.

Contents

Brad T. Clark

Brad T. Clark

Scott W. Roberts

Brad T. Clark

Cynthia E. Dott, Gary L. Gianniny, and David A. Gonzales

Pete McCormick

Lorraine L. Taylor and Keith D. Winchester

Brian L. Burke, Alane Brown, Betty Carter Dorr, and Megan C. Wrona

Becky Clausen, Teresa Montoya, Karletta Chief, Steven Chischilly, Janene Yazzie, Jack Turner, Lisa Marie Jacobs, and Ashley Merchant

Michael A. Dichio

Brad T. Clark

Andrew Gulliford

From Gold Medal to Gold Metal Waters

Brad T. Clark

More than 500,000 abandoned hardrock mines are scattered across the American West, a legacy of the boom-and-bust cycle of resource development. Estimates for comprehensive cleanup range from $36 million to $72 billion (Moyer 2016). At many mine sites, acidic mixes of heavy metals have drained unchecked for decades from the myriad shafts, tunnels, and portals (or so-called adits).

From a national perspective, millions of dollars are lost each year from the paucity of royalties paid by private enterprises on the wealth theyve extracted from beneath the public domain. Ever since manifest destiny lured explorers and fortune seekers west, profits from hardrock mining have been privatized while environmental impacts remained socializedculminating in what Pulitzer Prizewinning historian Vernon L. Parrington (1930) referred to as the Great Barbecue of the American West.

In Colorado alone, the Colorado Division of Reclamation, Mining, and Safety (CDRMS) estimates that there are at least 23,000 abandoned hardrock mine landsclassified as lands where mines operated prior to 1975, when the state began to establish limited forms of mining and reclamation standards. Today, these hardrock mine lands impact water quality in approximately 1,645 miles of streams and rivers.

Remediation efforts have been mixed, often stymied by a combination of outdated laws, funding woes, and ill-enforced regulations. Local politics, persistent NIMBY-ism, and liability concerns have further frustrated policy development and comprehensive restoration effortsincluding National Priorities List (NPL) designation under the 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), henceforth referred to as Superfund. All the while, acid mine drainage (AMD) from many of these ticking time bombs has contaminated watersheds and river basins on which tens of millions of westerners increasingly depend.

Whether its 100,000 or 500,000 [abandoned mines], thats hundreds of thousands too many... the Animas River spill has alerted the nation to the much more broad problem that many people were not paying attention to before.

Ty Churchwell, backcountry coordinator, Trout Unlimited, cited in Quiones 2015

The Gold King Mine (GKM) Spill

On August 5, 2015, the issue of AMD was thrust into the public and political spotlight with the unintended release of 3+ million gallons of subterranean mine water, carrying 880,000 pounds of heavy metals from the entrance of the abandoned Gold King Mine (GKM) into Cement Creek, a tributary to the Animas River in southwest Colorado. Just upstream from its confluence with the mainstem Animas, Cement Creek flows through Silverton, Colorado, the administrative seat of San Juan County. The Silverton area thus became the primary source associated with the spill, where an estimated 120-plus historic mine sites have contributed to AMD for decades (CDRMS 2015). Even prior to the arrival of hardrock mining in the area (circa 1870s), naturally occurring acid rock drainage (ARD) from the underlying geology had degraded water quality for millennia.

Soon after the spill, the entire Animas turned an unusually bright, yellowish-orange color below its confluence with Cement Creek, prompting local officials to restrict public access and suspend multiple municipal intakes and agricultural diversions in Colorado and New Mexico. Throughout the river basin, local communities, Native American reservations, irrigated agriculture, and recreational and wildlife areas were inundated. States of emergency were declared in Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah, as well as by the Navajo Nation Commission on Emergency Management.

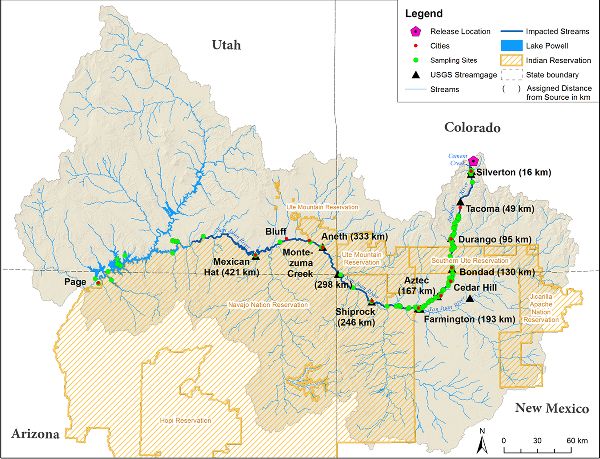

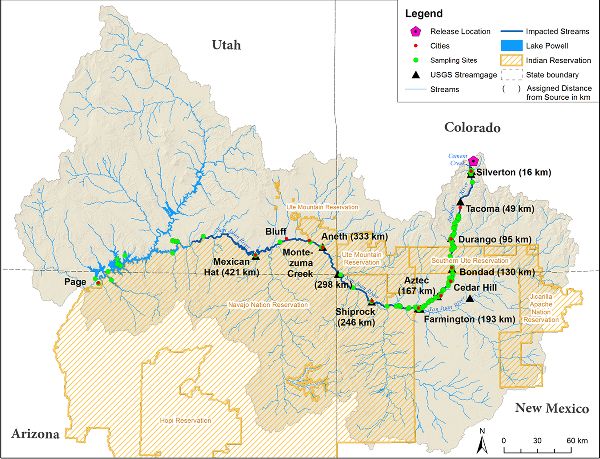

Figure 0.1. Path of the GKM Plume along the Animas and San Juan Rivers. Courtesy, One Year After the Gold King Mine Incident: A Retrospective of EPAs Efforts to Restore and Protect Impacted Communities, US Environmental Protection Agency, last updated August 1, 2016.

Nine days after the initial spill, the toxic plume reached Lake Powell in southeast Utah. All the while, local, national, and international media outlets capitalized on the highly visible, sensational event. The seemingly pristine river in the scenic and diverse corner of the Southwest had turned into a dayglow-orange conduit for acidic, heavy metalladen water on an inexorable path to the nations second largest reservoir.

Calls for a strong political response and policy reforms quickly materialized, prompting many to reconsider Superfund listing(s) and anticipate additional changes to existing policiesnotably the 1972 Clean Water Act (CWA) and the 1872 General Mining Law. By drawing insights from multiple disciplinary perspectives, this volume adds rich understanding of and context to the dramatic events following the 2015 GKM spill and the ongoing saga of AMD and abandoned mine reclamation across the American West.

Next page

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.