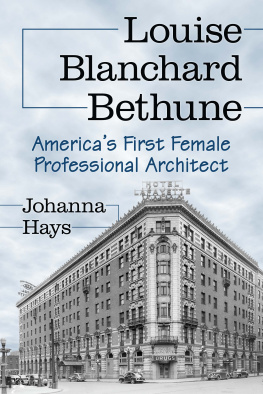

Louise Blanchard Bethune

Americas First Female Professional Architect

JOHANNA HAYS

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

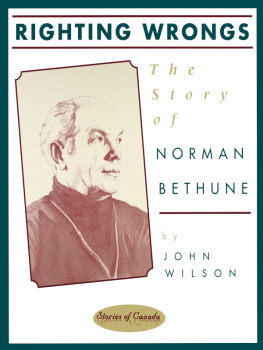

Title page: A portrait of Louise Blanchard Bethune in A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred Seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life by Frances E. Willard and Mary A. Livermore (Buffalo: Charles Wells Moulton, 1893). This is the only known portrait or photograph except for a watercolor done from this portrait.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1354-3

2014 Johanna Hays. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: The Hotel Lafayette, 1902-04, downtown Buffalo on Lafayette Park (courtesy of Buffalo History Museum, used by permission)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Preface

Americas first female architect, Louise Blanchard Bethune, was not simply a nominal architect who designed houses for herself or wealthy friends; she was one of the most successful architects practicing in late nineteenth-century Buffalo. Bethune belonged to the influential group of pioneer American architectsDaniel Burnham, John Root and Louis Sullivanall of whom supported her in becoming a fellow of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). Bethune had the additional distinction of opening her architectural practice at twenty-five, a far younger age than her more famous colleagues. She was fully apprenticed and trained, and held several offices in the AIA professional organization. Louise Blanchard Bethune was not only the first woman architect in the United States but the first woman architect with a full-time profitable practice in a powerful commercial and industrial city of the nineteenth century.

Through a quarter-century of successive economic expansion and depression, Bethune maintained a financially successful practice while promoting professionalization of architecture by participating in the development of licensing standards for the profession. While few women followed Bethune into the profession until a century later, her status in the AIA opened the architectural profession to women, and she served as a role model for those who have followed.

The nineteenth century was a time of transition from medieval building techniques to twentieth-century engineering and materials. Bethune was not just another boring nineteenth-century architect doing iterations of historic styles who happened to be female. Bethune built for the love of a variety of architectural puzzles. She left many landmark structures and equally important advances to a profession in transformation. She was an innovator and standards setter whose influence stretched far into the twentieth century, and her success counters almost everything we think we know about the cultural parameters for nineteenth-century women.

The chapters of this book have been divided into family history and childhood as it can be reconstructed; the seamless way Bethune decided to be an architect and secured an apprenticeship at the office of Buffalos most prestigious architect, Richard Waite; how she set up her practice and became a go-to firm for Buffalo and environs; the decision to pass on creating the Womans Building for the Chicago Worlds Fair; her impact on school architecturewhich had not previously existed; Bethunes embrace of technology and all its new issues for safety and utility; the range of public and private buildings requiring the development of new building types; and how inventing a path through life can emerge by simply doing what is necessary.

Bethune is heralded by historians searching for early professional women in spite of there being no record of her being a feminist or a promoter of feminist causes. No explicit statement on political feminism has been found and actually on feminism Bethune was very clear: The objects of the business woman are quite distinct from those of the professional agitator. Her aims are conservative rather than aggressive; her strength lies in adaptability, not in reform, and her desire is to conciliate rather than to antagonize. However, feminists interest in her did help preserve important details in her career.

Who was this woman who was an exemplar of gender success? Was there more to know? What kind of architect was she? How successful was she? Did she have a family connection to the profession? Louise Bethune left no personal papers, no letters beyond three in the AIA archive, no office records beyond one memo in the Buffalo AIA chapter archives, and no archive is yet located except for her buildings.

Yet Bethune was a famous woman in her lifetime and she was a subject in several turn-of-the-19th-century anthologies: Some Distinguished Women of Buffalo in American Womens Illustrated, October 7, 1893; Frances E. Willard and Mary A. Livermore, A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life, 1893; and National Cyclopedia of American biography, 1904, are the most informative and supply the information used by all following biographers. Bethunes death and the irony of her unchallenged position as Americas only woman professional architect were noted in Feminism and Architecture in The Western Architect in 1914.

An 1893 encyclopedia credited Louise Bethune with fifteen public buildings and several hundred miscellaneous buildings. More recent biographical sketches cite Bethune as architect of eighteen public schools in western New York State with the Lockport Union High School specifically mentioned, along with the Lafayette Hotel and several commercial and residential projects. If we can trust the veracity of the 1893 biographical sketch, published while she was alive, the verification of Bethune-designed buildings calls for fifteen public buildings in the first decade and far more additional buildings than recent biographers have listed. The innovations suggested by this assessment of her work indicated that there was much more to her career that required additional research.

Fortunately for our understanding of American cultural history, the women historians of the 1960s and 1970s began to look back for proof of successful and influential nineteenth-century women. Madeleine B. Stern in We the Women: Career Firsts of Nineteenth Century America (1962) consolidated the information available from the turn-of-the-19th-century encyclopedias into a narrative that became the basis of all following biographies. Stern listed just enough specific buildings (sixteen of the possibly hundreds Bethune designed) to illustrate that Bethune was not an amateur who designed houses for friends or simply a wealthy dilettante. Stern reestablished Bethune as a legitimate professional architect and emphasized the connection between Bethune, the Chicago Columbian Exposition Womans Building competition, and Sophia Hayden, the winning designer, that became the focus in following biographies of Bethune.