BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics series introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles in the series, please visit

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/series/bfi-film-classics/

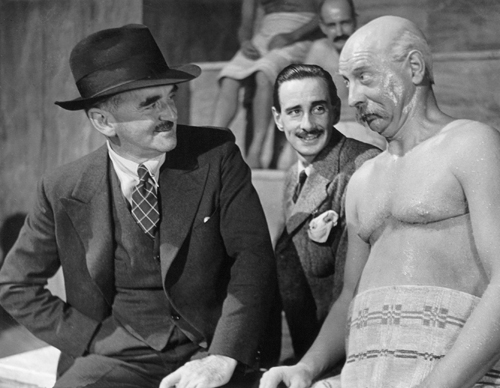

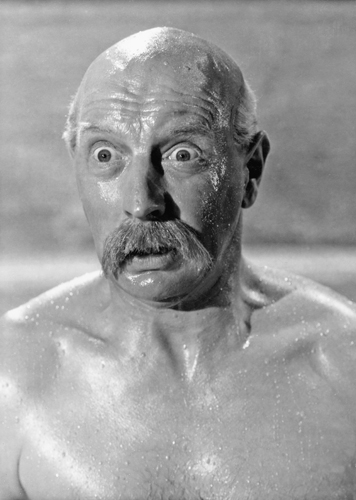

Roger Livesey with make-up artist George Blackler (centre) and David Low (left), cartoonist and creator of Colonel Blimp

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

A.L. Kennedy

Contents

I am particularly indebted to Kevin Macdonald for his humane and lovely biography of Emeric Pressburger and to Faber's excellent edition of the script of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, edited by Ian Christie.

The BFI The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was published in 1997. I was thirty-two years old and I had only recently gone entirely freelance. If theres occasional anxiety in my prose, bear in mind I was making my first foray into non-fiction and just generally tense. I was also trying to express a life-long devotion to Powell and Pressburgers movies, and I never have been good at expressing devotion. It all did me good, of course. Were supposed to express our deepest concerns and sustaining truths to each other. Were meant to get each other through. As I looked harder at The Archers work and why it appealed so deeply, I discovered elements I always wanted to be in my own work, elements essential to a culture that preserves our sense of our communal humanity. I wasnt yet old enough to point out that an unhappy childhood means youll never quite feel at home, but equally, lets you be comfortable anywhere.

I would recommend to you the section containing the professional manifesto that Pressburger sent Wendy Hiller, hoping to woo her for Colonel Blimp and The Archers. I gave it a good deal of space and, if anything, its artistic confidence, practicality and moral rigour inspire me more today than ever. In 1997, with my first movie distributed the preceding year, I thought it would guide me through the perils of the UK film industry. Ive never brought another script to the screen, but The Archers principles still influence all my writing. One day, I may fully reflect them.

In our age of risk-averse cinema, contagious despair and loathing, shake-and-bake, high-casualty plots and minimal dialogue to save on subtitles, entering Powell and Pressburgers point of view is restorative. It derives from their insistence on artistic necessities and the confidence provided by real world skills and a moral centre. Empathetic, inquisitive, moral, creative, unblinking: The Archers see everyone as human. You can either live up to the species, or you can fail it they will give you every chance. Its the outlook of Screwball Comedy, Capra, of projects that are often still too multi-toned and benevolent to pitch.

As I write, its a good time to watch Colonel Blimp again. Brexit is encouraging an emotional war footing in its supporters and reducing Englishness to an angry and paranoid vortex, history-free, but haunted by Spitfires. Colonel Blimp has always been heart-breaking, obsessed by impossible loves its a wonderful, inspiring agony now. The film is an exploration of exile, home, civilization and Englishness, replete with subtlety, humanity, intelligence and humour. Powell was, of course, English, but also a complex, transgressive outsider. Pressburger was a refugee chameleon who understood Englishness deeply enough to assimilate himself wholeheartedly into a land of dogged peacefulness, quiet voices, clipped lawns and dry wit. But their outsider eye sees everything: fear, wilful ignorance, snobbishness, cruelty. The values of Empire, so close to the values of the Reich, are interrogated and rejected. In all their films, The Archers are fascinated by identity: what it is to be Canadian, American, Irish, Scottish, different but equal. Its a philosophy increasingly embraced by a semi-independent Scotland: an experiment in a nationalism of inclusion, mixture, fluidity. Although Scottish identity was being increasingly explored in 1997, I didnt foresee Holyrood and the potential end of the Union.

The Archers examine the multiple strands of European experience, exile experience. Their Englishness and the Englishness of Colonel Blimp exists because of a swirl of other identities, individual and communal. And underlying every identity is a sense of cultural heritage, of beauty made and guarded. Leslie Howards long speech in The 49th Parallel was more of a disquisition than Pressburger wanted, but it remains any democratic activists answer to fascism a statement of values, the survival of which would make victory more than a triumph of killing capacity. An active wartime propagandist with European Jewish roots, Howard had formulated what could bring Britain through an existential conflict, something close to what became The British Way and Purpose. The Archers interrogate his position in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Germany, were told, has produced great artists. German prisoners listen to beautiful music how can people who love wonderful art do terrible things? While Goering hoarded stolen art and Hans Frank gloated over Lady with an Ermine, The Archers understood that art inspires what it inspires depends on the person.

My criticism of the UK press here is both too unsubtle and too restrained. I couldnt have guessed they would become a predominantly fraudulent and untrusted blight on our democracy, helping to drag us of a cliff of multiple self-harms. I also couldnt guess that Nazis would march and salute in British and American streets, or that openly fascistic advisers would influence a UK prime minister, underwrite a US president. Fresh from years of work as a writer in residence with social work departments, I didnt foresee the total collapse of social care and the welfare state. I didnt foresee the logic of Arbeit Macht Frei bringing starvation and humiliation, misery and despair, to the unfit. In 1996 you were unlikely to starve to death in Britain. State pensions relied on wider assistance for levels of comfort, but survivors of the Second World War could still thrive at home and in state-run care facilities. I sat with them, heard tales from Anzio and the Blitz, heard the extraordinary strength of resistance to acknowledged wrong, the complexities beneath the jingoism. The core values I saw in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp were still there: the joy in absurdity, the reality of pain, the empathy, the interest in others, the appetite for kindness, the awareness of actions consequences, the understanding of lasting strength.

I hope you enjoy the film. It was made in a dark time, was controversially non-conformist, and remains beautiful, compassionate and filled with light. Its the kind of thing to keep you company.

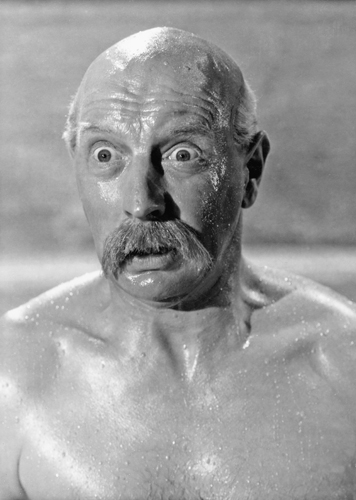

Clive Candy confronted by Spud

... how many times have I told you that a film is not words ... it is thoughts, and feelings, surprises, suspense, accident.

Emeric Pressburger to Michael Powell

In London, in Soho, in the early spring of 1996, I am walking down from Chinatown to the underground at Leicester Square and I am cold, very cold, and something catches in my mind: the inarticulate punch of somewhere I can only summarise as home. I am thinking of home.