This book is dedicated to the worlds ocean warriors.

You dare to live our dreams.

Contents

The navigator sticks his head up and says, Iceberg on the bow, one mile You are sailing under spinnaker at more than 20 knots, so you only have about three minutes to get the yacht around it. Its snowing and theres only 400 yards of visibility, so were navigating by radar. I need to know if I should go to the left or to the right to miss it. The navigator comes back up and says, Its on the starboard bow, then disappears. He reappears to say, Second iceberg on the port bow, half a mile.

Im saying, You are kidding me. Is this the same iceberg? Are they joined? Could this be the one iceberg with two peaks? Whats the gap between them? Its then too late to go either side. Weve got a berg to the left, a berg to the right and were going through the middle.

One of the younger crew turns around and says, What if they are connected?

I look at him and say, Then were going to die.

GORDON MAGUIRE WATCH LEADER, TEAM NEWS CORP

OCEAN WARRIORS. THATS WHAT THEY ARE.

Their bravado and ability to push themselves to the limits of endurance are almost beyond comprehension. And its all in the name of sport. In fact, what they achieve can make other extreme sports look like a romp in a park.

The men and women who compete have an insatiable appetite for tough competition, danger and the challenge of life-threatening experiences. They must cope with everything that heaven and hell can hurl at them. Raw nerve is an essential part of their kit. Yet in the sporting world they are virtual unknowns: ocean yacht racing is not exactly a highprofile spectator sport.

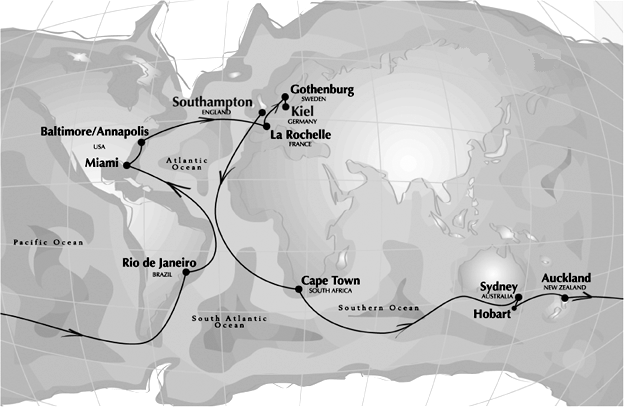

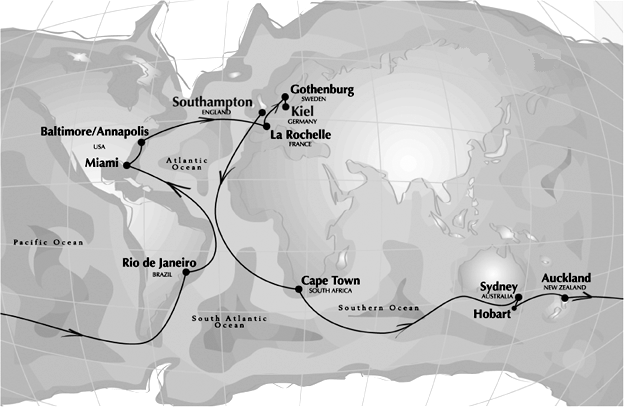

Theirs is a competition in which they must cover more than 32 000 miles in nine months and conquer the worlds oceans. The racing is nonstop 24 hours a day, seven days a week. On rare occasions they have three hours of uninterrupted sleep. To win the battle they must overcome the mind-bending frustration and oppressive heat of tropical calms. They must also master the white-knuckle terror that comes with a snowstorm-driven blast through a minefield of icebergs deep in the Southern Ocean. They face the full spectrum of the oceans moods, from tabletop-smooth seas to marauding monsters waves with near-vertical faces the height of a six-storey building. When these break, the avalanche of white water can easily engulf the yacht and its crew.

Surviving the elements is only part of this game; its also about beating the opposition. When conditions are at their worst, the competitors skills require them to balance on a razors edge between maximum speed and self-destruction.

And what awaits them at the end of this supreme test of endurance and yacht-racing skill? Nothing more than a crystal trophy and the knowledge that, if they win, they are the worlds best. Theres not one penny of prize money.

Are they mad masochists? They dont think so; well, most of them dont. There are some who hit the dock at the end and vow that they will sit under a tree for the rest of their life.

What follows is more than a story about a yacht race. Its about human endeavour, testing the limits of physical and mental endurance, team cohesion, and racing to the max. Its the story of the fortunes of eight of the best ocean racing teams in the world in the Volvo Ocean Race round the world and, in particular, the highs and lows experienced by one of the crews, Team News Corp, as they battle to become the worlds best ocean warriors.

THREE SAILORS LOST their lives when washed overboard in separate incidents in the first of these fully crewed races around the world, staged in 1973/74. Little wonder back then that when it was all over there were suggestions it would be the last such event.

But for those who completed the course the combination of their spirit of adventure and the formula for the competition proved to be a powerful blend: there was sufficient enthusiasm among competitors and would-be participants to go again four years later. And, most importantly, the sponsor liked it.

The initial concept for what would in 2001/2002 become the Volvo Ocean Race came from Colonel Bill Whitbread, of the Whitbread brewing family, and the Royal Naval Sailing Associations Admiral Otto Steiner, literally over a pint of beer. Titled the Whitbread Race, it would be the first time that a fleet of fully crewed racing yachts had faced the perils of the Southern Ocean.

The inaugural race, which started off Portsmouth in England, attracted a wide cross-section of sailors, from near-novices to some of the worlds best. And the yachts differed substantially in size (from 32 feet to 80 feet) and design from cumbersome cruisers to what were then very modern racers. Fourteen of the 17 starters completed the gruelling course. It was noted when the fleet rounded the worlds most notorious point of land, South Americas Cape Horn, that they had more than doubled the number of pleasure yachts to have completed that passage.

The race has subsequently been staged every four years and evolved from being little more than a cruising competition to a fiercely contested matchup: a 32 000-mile version of the most intense Saturday-afternoon dinghy race on a local waterway. It has attracted some of the worlds most famous sailing names Dennis Conner, the late Sir Peter Blake, Chay Blyth, Paul Cayard and Grant Dalton.

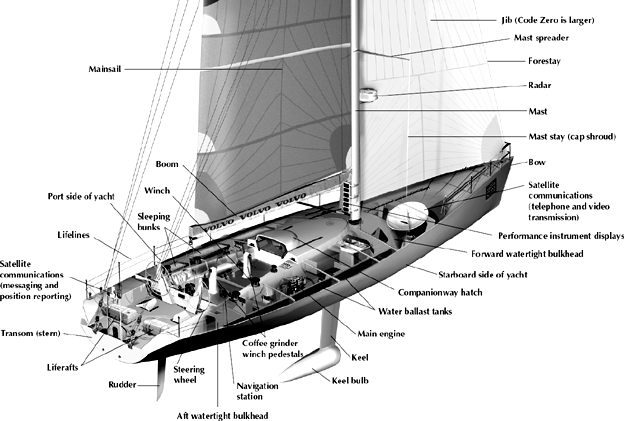

Like any extreme sport, the elements of danger and high drama have contributed greatly to the races appeal for both competitors and the international audience, which numbers in the millions. Over the years the races safety record has improved dramatically, but there will always be close calls. Take, for example, what happened to 31-year-old Australian sailor Alby Pratt in 1997. His moment came in the middle of the night when the 64-foot yacht he was aboard was negotiating a course through Bass Strait, the often dangerous stretch of water separating the Australian mainland and the island state of Tasmania. Suddenly, without warning, death was staring him down, winning the tug of war with the yacht that had just ejected him into the turbulent ocean. He felt as though he was trapped in a giants hand that was dragging him underwater. I thought I was gone, Pratt recalls. I was wrapped up completely inside the sail and knew there was no way out.

The events as they unfolded were terrifying. Pratt had been on stand-by below deck, off watch and napping, but ready to go should he be needed for a sail change. There was quite a big sea running, he says. The boat was pounding a lot and there was plenty of green water coming over the foredeck. We were just spearing through the waves. The call came for a change we needed something smaller. I went up onto the foredeck to help and clipped my safety harness onto a deck fitting. When we got the old sail down we had to carry it to the back of the boat. I unclipped so I could move aft and, just as I did, we nosed through a solid wave that submerged the bow.

It was like a submarine doing a crash-dive. With tons of water cascading across the deck there was no way Pratt and his crewmates could contain the huge Kevlar sail. It was no contest. The torrent tore it from their grasp and ripped it away.

Next page