Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

The city of Kyoto nestles in a basin traversed by several rivers and surrounded on three sides by mountains. To the south, it opens onto the Osaka plain. To the northeast is Mt. Hiei (848 meters), in the northwest is Mt. Atago (910 meters), and to the north Mt. Kurama (699 meters), beyond which wave after wave of mountains extend to the Japan Sea.

The Ancient Capital

From the fifth to eighth centuries, the Hata clan, a large family of Korean descent, occupied much of the future site of Kyoto, then known as the province of Yamashiro (the back of the mountains). They raised silkworms, controlled the imperial weaving industry, and enjoyed great prosperity. The Hata founded the Fushimi Inari and Matsuo Shrines at which prayers were offered for abundant rice harvests and silk production. They were also responsible for building Kryji in 603, well before Kyotos founding, to enshrine an image given them by Prince Shtoku (572-621).

In 784, the imperial court was relocated from Nara to Nagaoka, now a suburb in southwestern Kyoto. However, a number of deaths, including that of the crown prince, caused the emperor Kammu to consider the Nagaoka site inauspicious and to move the capital again. Invited by the Hata to use their land for hunting expeditions, the emperor was impressed by the beautiful scenery, the natural protection offered by the surrounding mountains, and the many rivers that flowed through the basin. In 794, Heianky, the Capital of Peace and Tranquility, was established.

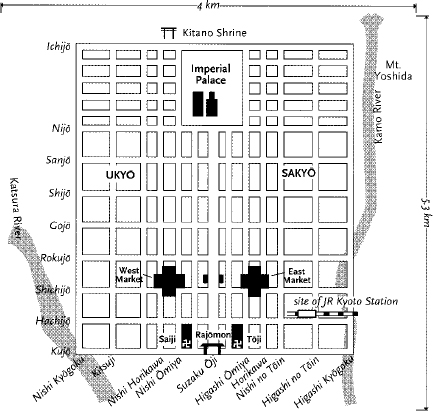

The new capital was laid out on a grid pattern modeled on that of the ancient Chinese capital of Changan (present-day Xian). The grid cut the city into large square divisions called ch, a feature preserved to this day in central Kyoto. Heianky was 4.46 kilometers east to west and 5.18 kilometers north to south, with the imperial palace in the center of the northernmost part of the city.

Suzaku ji, an eighty-five-meter-wide thoroughfare lined with willows and pines running south from the palace, divided the city into Saky and Uky, or Left and Right Wards. From east to west ran a set of numbered streets, which along with the broad northsouth avenues like Suzaku, formed a street grid that can still be seen on a modern map. Ichij to Kuj Dri (First to Ninth Streets) have run along the same roadways for more than a thousand years. At the southern end of Suzaku ji stood the main gate to the city, Rajmon (also know as Rashmon). Unlike Xian, which was surrounded by a fortress-like stone wall, no wall was built around Kyoto, though documents indicate that a small wall extended to the right and left of the Rajmon. The gate itself, more decorative than defensive, was a two-story structure almost thirty meters high and sixty meters across, painted a bright cinnabar red. Today, the only indication of its site is a single stone marker in a cramped playground. (A replica one-eighth of the original size is stored in the Municipal Art Museum.)

In 794, the capital boasted 80,000 dwellings and a population of 80,000 (todays population is about 1.5 million). By the time it was complete in 818, another 40,000 dwellings had been added and the population had increased to 120,000, making it one of the worlds largest cities at that time.

Near the site of present-day Kyoto Station were the East and West Markets, where a variety of shops sold silk, brocade, and damask, cotton for stuffing, ramie, thread, dyes, needles, leather, oil, metal goods, and oxen. One market was open the first half of the month; the other the latter half. Administration offices were located in each market marked by large, distinctive towers. Both markets were fronted by grounds spacious enough to accommodate the citizens who gathered to exchange gossip, buy new remedies from hawkers, or offer alms to mendicant monks. For reasons that are not clear, the East Market thrived, whereas the West Market closed in 825. Today, Kyotos central food market is located very close to where its predecessor, the East Market, once stood.

HEIANKY

Two large official temple complexes, Tji (East Temple) and Saiji (West Temple), were built on either side of the Rajmon in the Right and Left Wards of the capital. Tji became a temple of the Shingon sect when it was granted to the priest Kb Daishi in 823. Not much is known about Saiji, other than it may have functioned as an administrative site for the various Nara schools of Buddhism. Centuries later, a smaller Saiji became a Jdo temple, but when it fell into ruins, it was not rebuilt. While Tji still exists, the site of Saiji is now a park with a small mound, atop which stand two large hackberry trees. A sign in the park shows the original layout of the temple, which was the mirror image of Tji.

Today, Tji, designated as a World Heritage Site, offers visitors a glimpse of what a 1,200-year-old temple complex looked like. The Homotsukan museum [Open 9 to 4:30, spring and fall. Admission 500. Tel: 691-3325] contains many fine examples of Buddhist sculpture, as do the Kd and Kond, which can be entered with an additional 500. The Mied, to the west of the Homotsukan (no admission) conducts daily services to the temples founder, Kb Daishi, every morning between 6 and 7.

Originally, Heianky was oriented slightly to the west of the present center of Kyoto, and the Kamo River marked its eastern limits. However, much building took place east of the Kamo starting in the Ench period (923-30), at which time the western district went into a decline and reverted to rice fields, many of which still remain. The old capitals west boundary, Nishi Kygoku Dri, no longer exists except as the name of an area in the southwest corner of the city near the Katsura River. The temples and homes that once stood here are long gone. As the west remained undeveloped, the increasing eastward development turned Suzaku ji (present-day Sembon Dri) into the capitals western boundary. Teramachi formed the eastern boundary, and Kuramachi and Kuj Dri respectively became the northern and southern limits.

Over the centuries, fires, wars, and earthquakes changed the face of the city, and repeated rebuilding gradually moved the city closer to the Kamo River. It was in the late sixteenth century that Kyoto assumed its present shape, thanks largely to the patronage of the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-98). In the Tensh era (1573-91), Hideyoshi discarded the Right and Left Wards, redividing the city into Kamigy and Shimogy, the Upper and Lower Capitals. Hideyoshi relocated many temples to Teramachi (Temple District), where they may still be found today, along with shops selling religious items such as incense, altar furnishings, candles, prayer beads, and statuary. Wide streets were narrowed and the space filled in with housesbelieved by some to discourage unruly crowds from massing. With the loss of its broad boulevards, the Kyoto of the original planners vanished, and the grand dimensions that made it a ninth-century marvel disappeared.

Perhaps the most remarkable project of this time was the construction of an earthen defense embankment, called Odoi, around Kyoto. Building began in the early spring of 1591 and was completed seventeen months later in May of 1592. The speed with which this was done testifies to both Hideyoshis powers of organization and the size of the labor force at his disposal. It also reveals that the capital was in such a ruinous state after more than a century of civil war that the erection of the embankment did not have to be delayed by the displacement of large numbers of citizens.