FROM THE SCREENPLAY ANDREI RUBLV BY ANDREI TARKOVSKY, TRANSLATED BY KITTY HUNTER BLAIR

Introduction

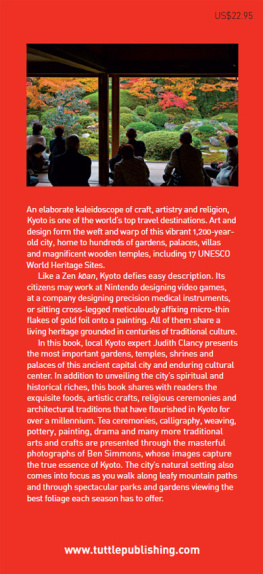

Yuku kawa no nagare wa taezushite shikamo moto no mizu ni arazu yodomi ni ukabu utakata wa katsu kie katsu musubite hisashiku todomaritaru tameshi nashi yononaka ni aru hito to sumika to mata kaku no gotoshi T his is the prelude to Hojoki , the great work of literary witness of medieval Japan by the recluse Kamo-no-Chomei ( 1155 1216 ). These lines are, together with the portentous tolling of the Gion bell at the start of the contemporaneous Heike Monogatari, the most familiar opening lines in Japanese literature. Supple and melodious, they prefigure the language and substance of the entire piece that follows. Hojoki was composed in 1212 , when its author was in his late fifties. A mix of social chronicle and personal testimony, it is a comparatively short work organized in three main parts. The first tells of a series of calamities, personally observed by Chomei, that overtook Kyoto in the late Heian Period.

The last part is a record of Chomeis thoughts and life in retirement from the world in the mountains southeast of the capital, a life brought about in part by disinheritance from a prominent ecclesiastical family, in part by a desire to find meaning and peace in a nonmaterialistic world. The two parts pivot on a central section that is a scathing commentary on the human condition. Basil Bunting, who based his poetic condensation, Chomei at Toyama , on an Italian prose translation of the work, wrote: The Ho-Jo-Ki is in prose, but the careful proportion and balance of the parts, the leit-motif of the House running through it, and some other indications, suggest that he intended a poem, more or less elegiac; but had not time, nor possibly energy, at his then age, to work out what would have been for Japan an entirely new form, nor to condense his material sufficiently. This I have attempted to do for him. However, there is nothing provisional about Hojoki , and nothing tentative, beyond Chomeis exhausted probing of the integrity of his purpose, indeed his questioning of his own sanity, toward the close of the piece. These very elements give the work an intense humanity from which it ultimately derives its timelessness.

There can be no question as to the essentially poetic intent of Hojoki . From the first lines, we are clearly aware of an enhancement of language that carries its subject in a crafted, rhythmic manner. Even someone ignorant of the Japanese language can detect in the romanized transliteration a restless rippling, and hear the stuttering gush of water over the consonants. There are countless other examples, for instance in the quickening of pace in the description of the fire. Words fly through the air like the cinders the writer is describing, in a flurry of staccato, journalistic in its best sense. This man was there , and eight centuries later, he is still out of breath.

Again, later, in one of the most beautiful passages of the whole work he describes his companionship with a little boy, son of the warden of his mountain retreat; the language rises in visionary warmth as he describes solitary nights by his fireside, recalling his friends, hearing in the song of the copper pheasants the voices of his parents. This musical chargewhat Pound termed melopoeia is coupled with a compelling visual dimension ( phanopoeia ). Again, from the opening lines we gain a clear pictorial image of the rushing water, the gathering and dispersing of the froth on its surface, but also of a setting of hillside rocks through which this river flows. Elsewhere, we see the fire engulfing Kyoto, spreading like an unfolding fan, just as later we share the visions of the fishermens braziers in a little cooking fire. Then beyond this, most subtly, we encounter logopoeia , Pounds dance of the intellect among words, in which words are employed not only for their plain meaning but for their cargo of nuance, irony, or association. Thus, in the opening lines, a mans home is sumika , carrying the resonance of abode, dwelling, even approaching its modern biological sense of habitat.

Or when describing the city of Kyoto as tamashiki-no-miyako , we are not to understand this as a capital glittering like a veritable jewel but more as a kind of gilded lily, glorious in the direction of vainglorious. In structure too, as Bunting noted, the intention is poetic. The three sectionsthe disasters, the central pivot, and the latter hermitageare held together by the recurring image of the House. First, we see the lofty towersperhaps indeed jewel-encrustedof the well-to-do. These appear almost to have a life of their own as they assert their dominance over the rooftops of lesser citizenry. But all the houses, together with their inhabitants, are buffeted and destroyed with supreme indifference by nature and by man alike.

A fire that starts in an entertainers lodging house levels a major section of the city, reducing to ash both imperial chambers and common dwellings. A whirlwind destroys fences, so that you are no longer able to differentiate between your property and that of your neighbor. A capricious imperial decree orders the removal of the capital, so the ambitious office seeker must dismantle his house, float it down the river to the new location, re-erect it, and then, upon a new decree, pull it down again. Famine and disease reduce the most distinguished households, and even chopping up your home for firewood will provide heat for no more than a day. And of course an earthquake simply brings the whole thing down around your ears. The Imperial Household is transferred to present-day Kobe, where the new palace has the aspect of a log cabin, comically conceded by Chomei to be not without a certain antique charm.

Through the latter part of the book, Chomeis own social decline is conveyed in the progressively smaller houses he builds, deeper and deeper in the mountains. He finally builds a tiny hut, which gives Hojoki its nameliterally Writings from a Place Ten Feet Squareand which in a memorable image becomes so overgrown we feel it almost melting into the side of the mountain. This sense of the little dwelling sinking into the earth is part of a further skein of symbolism, formed from the four elements of nature, that also binds the work together. The work starts with the confident rippling of water, and closes with Chomei well into my sixth decade / when the dew of life disappears. The violent earthquake that topples mountains in the first part of the work is mirrored in a more benevolent earth gently embracing the hermits last home. The gales and floods that precede the terrible pestilence stand in contrast to Autumn Breezes and Flowing Water , the songs he later plays to himself on koto and biwa.

![Kamo - How to Draw Cute Doodles and Illustrations: A Step-by-Step Beginners Guide [With Over 1000 Illustrations]](/uploads/posts/book/438310/thumbs/kamo-how-to-draw-cute-doodles-and-illustrations.jpg)

HOJOKI V isions of a T orn W orld Text by Kamo-no-Chomei translated by Yasuhiko Moriguchi and David Jenkins with illustrations by Michael Hofmann Stone Bridge Press Berkeley, California Published by Stone Bridge Press, P.O. Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707 tel 510-524-8732 sbp@netcom.com www.stonebridge.com The quotation on page is from Andrei Rublv by Andrei Tarkovsky, translated by Kitty Hunter Blair (London: Faber and Faber, 1991 ). Cover design by David Bullen incorporating a painting by Michael Hofmann Text design by Peter Goodman Text copyright 1996 by Yasuhiko Moriguchi and David Jenkins Illustrations copyright 1996 by Michael Hofmann All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. isbn 978-1-880656-22-8 F or the people of South Hyogo

HOJOKI V isions of a T orn W orld Text by Kamo-no-Chomei translated by Yasuhiko Moriguchi and David Jenkins with illustrations by Michael Hofmann Stone Bridge Press Berkeley, California Published by Stone Bridge Press, P.O. Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707 tel 510-524-8732 sbp@netcom.com www.stonebridge.com The quotation on page is from Andrei Rublv by Andrei Tarkovsky, translated by Kitty Hunter Blair (London: Faber and Faber, 1991 ). Cover design by David Bullen incorporating a painting by Michael Hofmann Text design by Peter Goodman Text copyright 1996 by Yasuhiko Moriguchi and David Jenkins Illustrations copyright 1996 by Michael Hofmann All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. isbn 978-1-880656-22-8 F or the people of South Hyogo

He hears snatches of conversation; the wind singing under the thatched eaves; the rustle of twigs... the full-throated, happy cry of swallows in the evening air. His eyes are filled with helpless anguish, like someone who has suddenly lost the power of speech at the very moment when he is about to say something terribly important, something crucial to everyone who might hear it.

He hears snatches of conversation; the wind singing under the thatched eaves; the rustle of twigs... the full-throated, happy cry of swallows in the evening air. His eyes are filled with helpless anguish, like someone who has suddenly lost the power of speech at the very moment when he is about to say something terribly important, something crucial to everyone who might hear it.