PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published in Great Britain by Penguin Classics 2013

Translation and editorial materials Meredith McKinney, 2013

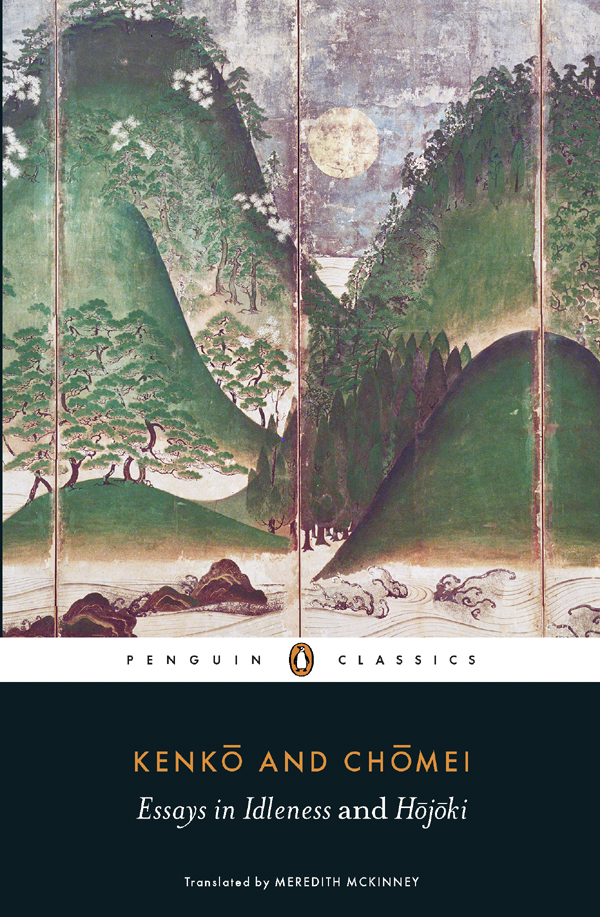

Cover: Detail from Spring Landscape with Sun, part of a six panel folding screen, 16th century. Kongo-ji Temple, Osaka, Japan / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

All rights reserved

The moral right of the translator has been asserted

Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

ISBN: 978-0-141-95787-6

Contents

PENGUIN  CLASSICS

CLASSICS

ESSAYS IN IDLENESS AND HJKI

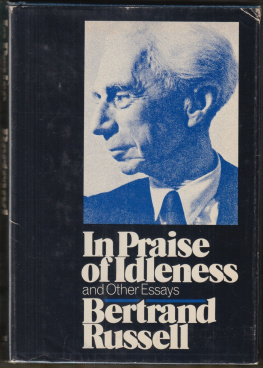

Kamo No Chmei (c. 11551216) was a prominent poet, essayist and musician associated with the court in Kyoto. At the age of fifty, personal setbacks and despair at the world led him to take the tonsure and retire to live in a hut beyond the city limits. Here, he wrote the three works for which he is now remembered Mumysh (Nameless Treatise), Hosshinsh (A Collection of Religious Awakenings), and the famous Hjki (Record of a Ten-foot-Square Hut).

Yoshida Kenk (or Kaneyoshi) (c. 1283c. 1352) was a poet, essayist and noted calligrapher. He took the tonsure probably in his late twenties, and underwent a period of rigorous monastic training, but for the most part continued to remain involved with life in the capital. The sole work for which he is now remembered, Tsurezuregusa (Essays in Idleness), a rich compendium of opinions and anecdotes, is counted among Japans greatest classics.

Meredith McKinney holds a Ph.D. in medieval Japanese literature from the Australian National University in Canberra, where she is currently a visiting fellow. She taught in Japan for twenty years, and now lives near Braidwood, New South Wales. Her other translations include Ravine and Other Stories by Furui Yoshikichi and, for Penguin Classics, Kokoro and Kusamakura by Natsume Sseki and The Pillow Book by Sei Shnagon.

Introduction

In a period roughly spanning the twelfth to fourteenth centuries in Japan, a vibrant and complex literary culture flowered from Buddhist teachings and practice. This book contains the two prose works that were the finest embodiments of that culture, and that still rank among Japans great classics.

The men who wrote these works were tonsured monks, who had formally dedicated themselves to the practice of the Buddhist Way; they were not, however, attached to any monastery, and one of them (Yoshida Kenk, 12831350) was actively involved in the social sphere of the capital (present-day Kyoto). In their different ways, these men belonged to a niche that gave them access to two contrasting worlds the mundane and the religious while allowing them to escape the more arduous demands of both. The freedom of their situation, along with its inherent tensions, was at the heart of the literature that they and others like them produced.

Buddhism in Japan had a long tradition of solitary practice for those who chose to distance themselves from the often intensely political world of the monasteries. The most impressive of these hermit ascetics were considered holy men, and accorded almost saintly status. Tales of their wisdom and the severity of their ascetic practice circulated among both monks and laity. They represented one extreme of the non-monastic Buddhist practitioner; the other was the figure of the lay monk or shami (translated here as novice), who chose to take the tonsure as a means to retire from active engagement with the world, often in response to increasing age or to a setback in his career, but who frequently remained at home and continued to have limited dealings with the world. Such a gesture could be calculated or impulsive, sincere or merely formal.

Between the two extremes, and sometimes tending now towards one and now the other over the course of a life, was a wide range of men (and occasionally women) who went by a variety of titles, but generally fitted somewhere within the concept of the recluse monk, or tonseisha. These people, who inhabited a fluid realm in which they were largely their own master and could live as they wished, were the men who produced what is commonly called the literature of reclusion, whose two finest prose examples are Hjki and Essays in Idleness (Tsurezuregusa).

Kamo no Chmei (c.11551216) provides us in Hjki with the quintessential figure of the literary recluse. He has built for himself a tiny hut, exactly large enough to contain the essentials for life, in a remote place far from the distracting presence of others, where the peace and beauty of the natural surroundings are conducive to calm contemplation. His life is one of utmost simplicity. Prominent on the wall are two Buddhist images, with a sutra (a Buddhist scripture) placed on the altar before them, where he performs his religious devotions. The only other contents of the hut, apart from his bed of bracken, are a shelf that holds a few carefully chosen books (a religious tract, poetic anthologies and musical treatises) and two musical instruments. He divides his time, as the spirit takes him, between performing his devotions and reading the sutras and playing his instruments and reading or composing poetry. Despair at the sufferings of this world has led him to choose this life, but he is by his own admission a happy man.

The hermit-aesthete of Hjki is consciously following a venerable lineage reaching back to ancient China, some of whose finest poets belonged to this tradition of reclusion. In the Japan of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when Chmei chose to live like this, his more immediate models were other Japanese non-monastic monks, of his time or earlier, who combined pursuit of a spiritual calling with an equal dedication to the arts, most particularly that of poetry. They are sometimes referred to as

CLASSICS

CLASSICS