Raise your head to see the way, lower your head to do the job.

~ Chinese idiom

Copyright 2019 by Staffan Nteberg.

First Skyhorse Publishing edition, 2020.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Racehorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Racehorse Publishing is a pending trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020930865

Interior artwork by Staffan Nteberg

Cover design by Kai Texel

Cover artwork credit: Getty Images

Print ISBN: 978-1-63158-548-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63158-549-4

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

PREFACE

PERSONAL PRODUCTIVITY SYSTEMS HELP us to manage our personal time in the most efficient, productive, and effective way. However, systems that are too complicated, too rigid, or too time consuming will sooner or later be rejectedno matter how much potential they have to help us.

Rigid personal productivity systems are often developed by engineers who normally program computers. Even though they try to specify in detail how we should act in every possible scenario, they wont be able to describe most situations. The world is too complex for rule-based systems. A better approach is to replace the rules with good practices. Then human intuition can come to the rescue.

Complicated personal productivity systems are created by personal productivity gurus. They love to have a multitude of lists, protocols, and tools. But if inventing personal productivity systems isnt your profession, then youll want an easy system that can be implemented promptly and can rapidly result in productive habits.

Time-consuming personal productivity systems are usually implemented in your organization by management consultants. They persuade top management that employees are lazy and accordingly must constantly report upwards. These systems tend to consume more resources than they free up.

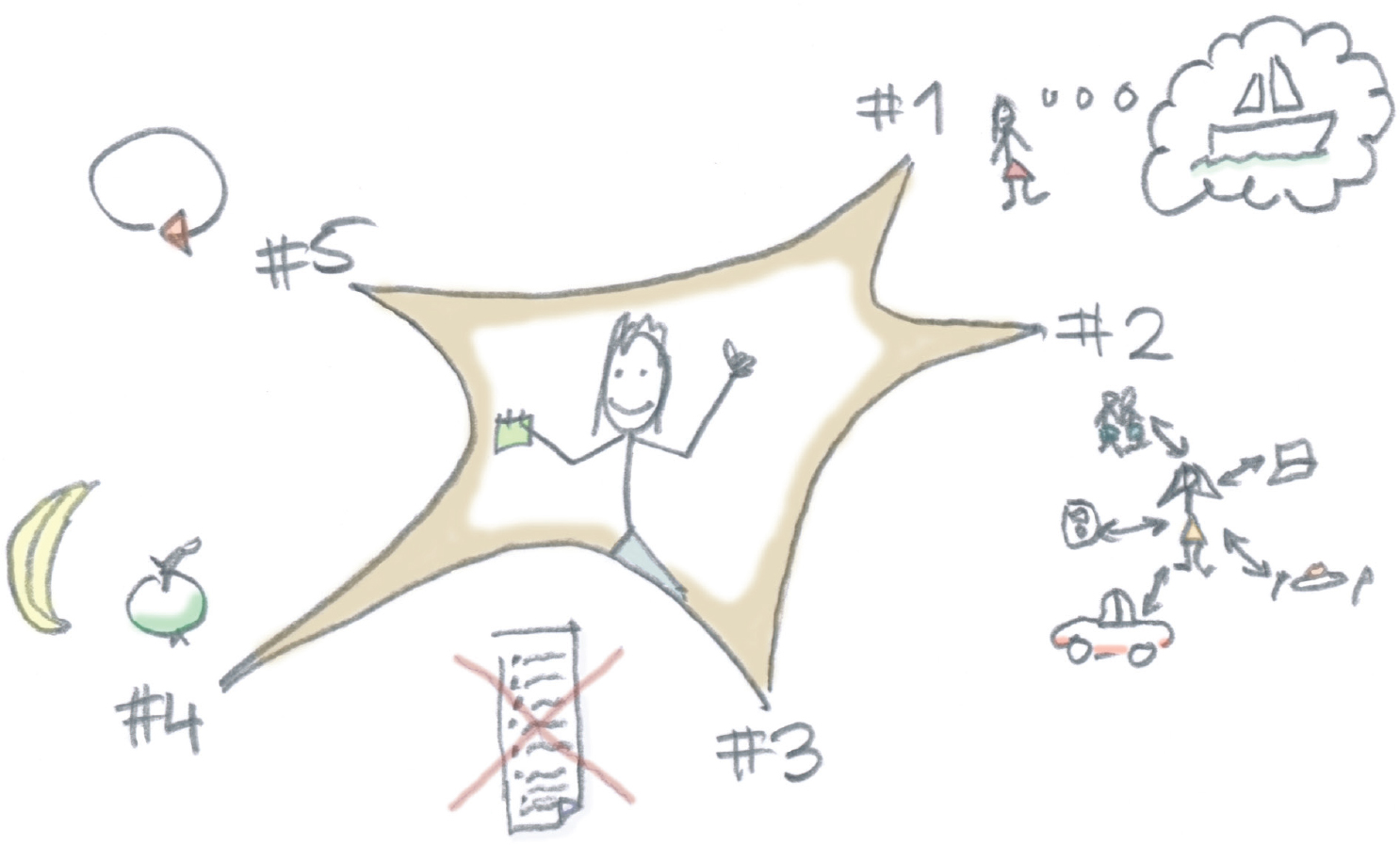

Monotasking is a powerful system based on switching between prioritizing and focusing. Its flexible, easy to learn, and minimally time consuming. However, it is still very capableand fun. It also embraces the ability to evolve. You can start with this textbook version and then adapt it to your circumstances when you find that you would benefit from that.

This book is organized in seven chapters. The first provides an overview of the monotasking method, and the remaining chapters cover the six areas in which it is most important to achieve success in order to be productive:

Cut down on tasks to do

Focus on one task now

Never procrastinate

Progress incrementally

Simplify cooperation

Recharge creative thinking

The chapters are independent and can be read in whatever order you like. However, if you want to succeed with the monotasking method, you should understand all of them. My recommendation is to use the panorama cue while reading this book. It will give you a good idea of how you want to customize monotasking to your special circumstances.

I hope youll enjoy the book and benefit from monotasking!

// Staffan

INTRODUCTION

THE FIVE AXIOMS OF MONOTASKING

LITTLE DID THE YOUNG and curious psychology researcher Bluma Zeigarnik know that her seemingly trivial observation in a caf would change the game of personal productivity. This was back in the 1920s, but today we are still struggling with how to best use her findings in the modern environment of office work.

Bluma was fascinated by a waiters ability to remember what everyone had ordered when someone called for the bill. It didnt matter that Blumas friends had spent hours in the caf, ordering multiple times. The waiter successfully recalled everything.

Then, half an hour after paying, they asked the waiter to rewrite the check. He couldnt. The surprising answer was, I cant recall what you ordered, since youve paid the bill. Until the order was paid, it was available in detail in the waiters memory. After that, it was forgotten.

Could Bluma confirm her theory in a scientific experiment? She let 164 people know that they would perform about twenty tasks. What she didnt tell them was that half of the tasks would be interrupted before they could be completed. The tasks were interrupted in such a way that no one could suspect that the interruptions were a deliberate part of the experiment. Some tasks were manual work, such as constructing a box of cardboard or making clay figures. Others were mental problems, such as puzzles and arithmetic. Following the last task, participants were asked to recall the tasks they had worked on. Blumas initial hypothesis from the caf was proven correct. Approximately twice as many of the unfinished tasks were remembered compared to the completed ones.

The fact that we remember unfinished or incomplete tasks better than the completed tasks usually goes under the name Zeigarnik effect . In order to remember it better, I prefer to call it the waiter effect . As well see later in this book, it can cause us problems. But we can also use it to our advantage. For example, leaving the office in the middle of a task helps you get started easily the next morning, eliminating some of that before-lunch procrastination. This leads us to the first axiom:

Axiom #1: Started tasks will unconditionally demand space in our daily thinking until we either complete them or delete them.

Every time we switch from one task to another, our brains executive control does two things. First, it activates the goal shifting: I did this, now Ill do that. Second, it creates the context for the new task. The latter is called rule activation .

Switching tasks consumes time. One switch can take as little as a tenth of a second, but during a day of constant switching, it might consume a significant part of your productive time. While looking productive, youre actually wasting a good amount of time between tasks.

Task switching also induces errors. Clearing the working memory and reloading the rules of the current task over and over isnt the best foundation for problem solving. The more complex your task, the more errors will arise because of task switching.

Repeated task switching also reduces what is popularly known as emotional intelligence, or EQ. The switching leads to anxiety, which in turn raises levels of the stress hormone cortisol in the brain. This may contribute to aggressive and impulsive behavior.

Finally, task switching is energy intensive. It burns up oxygenated glucose in the brain. Unfortunately, that is exactly the fuel we need to stay on a task. Task switching thus initiates a vicious cycle, increasing the risk of even more task switching. Depleting these resources also makes us feel exhausted, and even disoriented, quite quickly. Heres the second axiom:

Next page