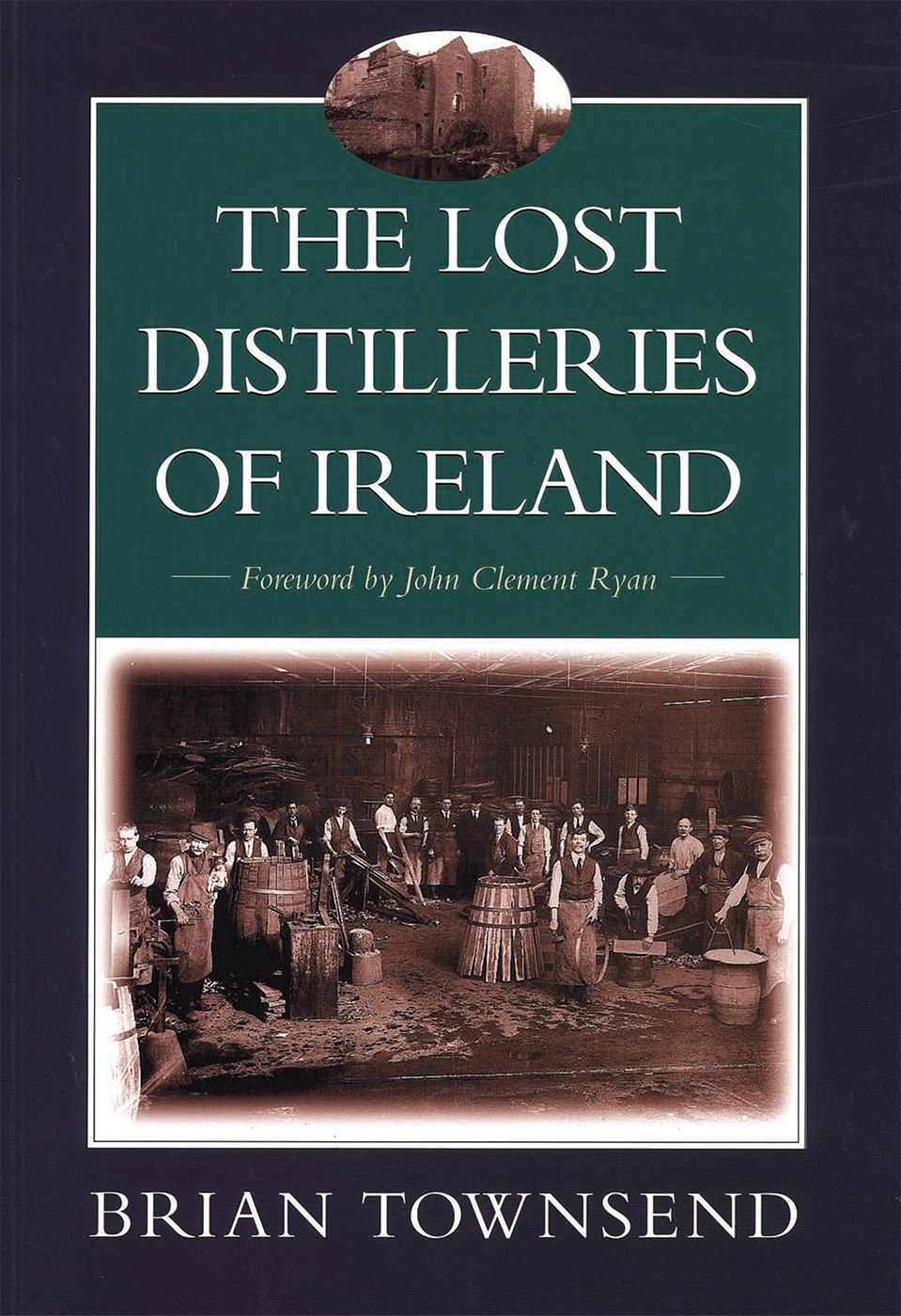

THE LOST DISTILLERIES OF IRELAND

BRIAN TOWNSEND

Foreword by John Clement Ryan

NEIL WILSON PUBLISHING

FOREWORD

I rish whiskey has already had two Golden Ages in its more than 1000 years of history: the first was when the monks brought uisce beatha to Ireland, and the second is admirably illustrated in this perceptive work by Brian Townsend, a fine scholar of the fascinating history of whisk(e)y. Undoubtedly the distillers of Ireland were ahead of their Scots cousins in harnessing the skills of the Industrial Revolution to launch this second Golden Age and to change their craft from a cottage industry into a world-beating industry.

One of the losses from the demise of this second Golden Age has been not only the closure of many distilleries, as Brian has detailed in this excellent record, but also the passing of the great Victorian paternalism of the Irish whiskey industry. As a boy I remember going to John Power & Sons Johns Lane Distillery with my grandfather Willie Ryan, and meeting the craftsmen stillmen, coopers, coppersmiths who themselves were the third and fourth generation of their family to have worked there. In those days a job in the distillery was a job for life the firm would look after you with a good wage, a rudimentary but effective medical scheme, a fair pension, and a great bit grog before going home after a hard days work. In the previous century when distilling was seasonal Sir John Power provided a lodging house in Dublin adjacent to the distillery where, for a shilling a week, his Wexford workers had plain and safe accommodation during the winter distilling season. He also had rebuilt the village of Oylgate in Co Wexford, beside his country seat at Edermine, near Enniscorthy, where the men could live the summer in comfort and retire with dignity in their old age.

My father John Ryan, his brother Clem and their cousins Frank, Joe and Reggie OReilly, all great-nephews of Sir Thomas Talbot Power, were the directors of John Power & Son after the passing of that great period, and had the foresight to see that there would be no future for the Irish whiskey industry unless they could re-launch the export trade; during the 1950s there had been fierce competition between Jameson, Powers and Cork Distillers for dominance of the home market, and none of the three had any time, effort, energy or manpower left over for developing exports. So in 1966 they persuaded the directors of the other two companies to bury the hatchet of 200 years of competition and merge to form the Irish Distillers Group. Bushmills joined this family in 1972 and the renaissance was under way.

For my part I have just retired after 27 years, having joined the group in 1969 as the first young salesman in that infant export division. My boss at the time was my cousin Reggie OReilly, one of the great buccaneers in the industry. My only regret is that when I retired I was the last descendant of any of the founding families. But I have had the privilege and pleasure of seeing the sprouting of the first seeds of the third Golden Age of Irish whiskey, now coming to fruition with Jameson selling over a million cases worldwide, in the capable hands of Richard Burrows and our sister companies in the Pernod-Ricard Group.

Perhaps Brians remarkable work will stand as a milestone in the history of Irish whiskey, which in passing the industry moves forward to a new era of prosperity and success. Let us never forget the past, but always look forward to the future.

Slaint, agus saol agat!

John Clement Ryan, Booterstown, Co Dublin.

April, 1997.

INTRODUCTION

T his book seeks to record, extol and celebrate a great enterprise that in bygone times helped to put Ireland on the world map. That enterprise was the Irish whiskey industry and the 30 or so 19th-century distilleries which were its productive seedbed. It is a sad fact that in the past 100 years that grand number of distilleries has shrunk to just three. Of those, only one Old Bushmills is an original distillery in the eyes of the purists. Of the other two, one is a newcomer born in the 1980s, Cooley in Co Louth, the other is the vast, modern, multi-still plant built in the mid-1970s at Midleton, Co Cork.

Although the world today regards Scotland as the stronghold and main producer of whisky, those epithets long belonged to Ireland. From myth and folklore rather than accurately recorded history, one can surmise that uisce beatha may have been distilled in Ireland as early as 1000 AD, nearly 500 years before the first record of distilling in Scotland. For centuries Ireland was to keep its supremacy, only to yield it to Scotland in the twilight of the 19th century.

Throughout much of the 19th century, the whiskey powerhouse of the world was undoubtedly Dublin, whose half-dozen distilleries had a production capacity of nearly 10 million gallons per annum and in some years accounted for up to one gallon in seven of the whiskies distilled in the British Isles. Pot still whiskey from the Dublin Big Four John Jameson, William Jameson, John Power and George Roe was consistently regarded as the finest in the world and the liquid yardstick against which almost all other whiskies were measured.

Although by the early-20th century Scotland had become the main whisky producer in the world, with an output roughly twice that of Ireland, that volume came from over 130 distilleries whereas Irelands spirit poured from fewer than 30. In Scotland, distilleries producing more than 100,000 gallons a year were rare: in contrast, Ireland had only one or two distilleries with an annual output below six figures.

The Dublin distillers with the citys brewing brethren had wealth, power and political clout in abundance. Just as Guinness was the king of porter and ebony monarch of beers, so Dublin whiskies bearing the names Jameson, Roe and Power were venerated, not without reason, as the best in the business. The ultimate left-hand compliment to Dublin whiskey was paid by Scotlands growing Distillers Company Limited (DCL) when they launched the Phoenix Park distillery in Dublin in 1878, barely a year after the company was formed. Their brochure to potential investors bluntly stated,

It is a very important fact that the quality and reputation of Dublin-made whiskey is in general equivalent to a premium of one shilling a gallon, or an additional 25%, over whiskey made in other parts of Ireland.

The demand for Irish whiskey is practically unlimited at present. The deliveries of Scotch whiskey into Ireland (principally at Belfast for reshipment) and into England (which is sold to the consumer as Irish whiskey) would it is calculated equal the produce of 20 such distilleries as the proposed one.

There are considerably over 100 distilleries in Scotland, in Ireland not 20, while the demand for Dublin whiskey is estimated at more than five-fold that for Scotch at present.

Although their arithmetic was far from accurate, their message was crystal clear: it was vital DCL gained a foothold in this highly-regarded producer territory. As the DCL brochure admitted, Irish whiskeys quality and ascendancy was then such that a lucrative trade bitterly criticised by the Dublin distillers had evolved that sent cheap, anodyne Scotch grain whisky to Ireland to be mixed with coarse Irish provincial whiskey, then reshipped with Irish barrel markings to English buyers who paid a premium in the belief they were buying good, authentic Irish whiskey.

Despite this problem and others, Irish whiskey was at its zenith around 1870-90. Yet a century later, we must lament a shrunken industry that, on occasion, came close to total collapse. As I have said, from around 30 Irish distilleries in the 1890s, the tally is now just three, though the modern distilling complex at Midleton produces through a combination of various pot and patent stills, distilling sequences and blending facilities a swathe of differing whiskies of enduring pedigree.