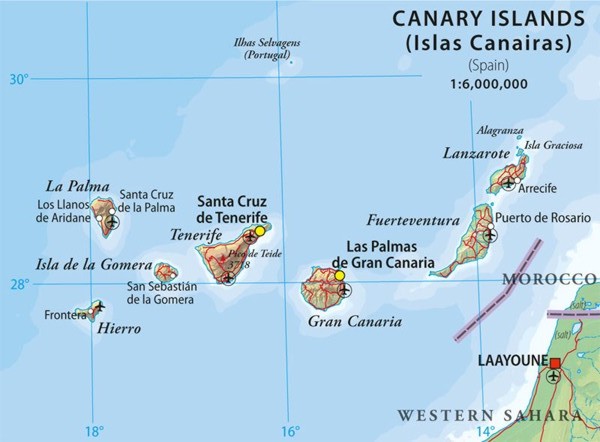

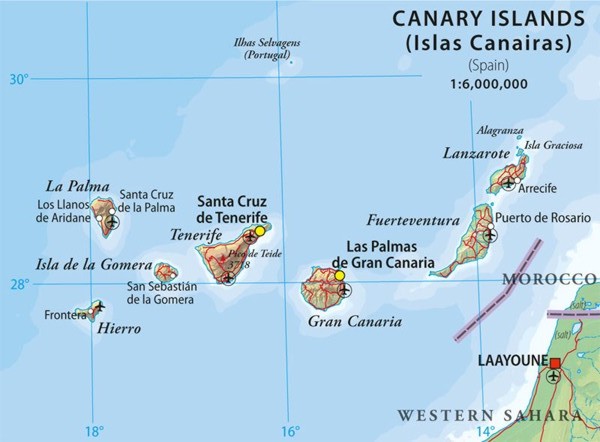

Canary Islands

Introduction

With peninsular Spain over 1,500 watery km (930 miles) to the north, a look and feel quite distinct from the motherland becomes quickly apparent once you're standing on the tierra firma of the Canary Islands. The steady, year-round spring temperatures - which can come as a godsend while the rest of Spain endures its tempestuous swelters and freezes with no happy medium in sight - make exploring the wilder spaces as comfortable as a snooze on one of the hundreds of beaches. If natural, the beaches will be volcano dark and hot to the soles of sensitive feet or, if manmade, cool with Saharan sand like that of Tenerife's crowded Playa de las Americas. The many landscapes of the islands are a mix of rare and otherworldly scenery in settings that range from lush volcanic highlands to arid, semi-desert flats.

Though scientists have put forth a plausible explanation concerning the origin of these islands, ancient myths linger on and add a certain element of intrigue to the Canaries. Ancient Greek poets and philosophers associated them with the mythical Elysian Fields, the Garden of the Hesperides, and the lost continent of Atlantis - fantastical, Edenesque realms somewhere beyond the Pillars of Hercules (now recognized as the Strait of Gibraltar on Spain's southern coast).

Since at least Roman times the Canaries have been referred to as the "Fortunate Islands," owing to their terrific climate, which averages 22C (72F) annually. The moniker endures along with the myths, and no doubt the traveler seeking an idyllic island respite will appreciate such an incomparable setting.

Most likely, the seven islands were created through two separate geological events. Lanzarote and Fuerteventura, the easternmost and oldest of the archipelago, share characteristics with the nearby African continent - arid conditions, a hot Sirocco wind that blows in from the Sahara for weeks on end and a lower average elevation. That low elevation is incapable of catching the moisture-laden clouds that hang up on the mountains of the other five islands, whose northern faces are carpeted by lush vegetation and blessed with conditions far more favorable to agriculture (notably the ubiquitous Canary bananas). It would appear that plate tectonics caused Lanzarote and Fuerteventura to split at some time in the distant past and, through the ages, drift farther and farther out to sea. The westernmost islands of Tenerife, Gran Canaria, La Palma, Hierro and Gomera, in contrast, were gradually thrust above sea level through volcanic eruptions over the past 20 million years. Though none of the numerous Canary volcanoes are currently active, many remain dormant. The most recent eruption occurred in 1971 on La Palma, and before that in 1909 when Teide last erupted. Their devastating potential intact, these island landscapes will continue to evolve, to build up as erosion breaks them down and plate tectonics moves them steadily across the Atlantic at a rate of one cm or .39 inch per year.

Tenerife

History

After almost a century steadily expanding their reign over the islands, the Spaniards completed the conquest of the Canaries in 1496, a few years after Christopher Columbus had made his fated layover on the island of Gomera. From there, he set sail in search of a westward passage to Asia, which, a month later, led to the discovery of the West Indies. Long before this time, though, the Canaries had been utilized as an Atlantic crossroads due to their convenient proximity to Europe and Africa. With Columbus' exploits and the realization that these islands were not, in fact, the end of the world, the Canaries' ideal situation as a way-station on newly expanding exploration routes soon drew ships waving other European flags. The influence of not only the Spaniards but the neighboring Portuguese and sizable representatives from most other Western European countries came to influence the culture of the islands; it also led to the subjugation and ultimately hastened the disappearance of a mysterious native culture that, like the native flora and fauna, had prospered undisturbed on the island since ancient times.

The newly arriving explorers described these Gaunches, as they came to be known, as a race never previously encountered, in appearance tall and fair like northern Europeans, but possessing a unique culture in which cave dwellings, nature worship and complex mummification techniques were the norm. While their origins remain a mystery, ethnologists wager that the native islanders were of African descent, having arrived some time during the first millennium before Christ. The Gaunches would not survive the influx of foreigners, but their rudimentary dwellings are still seen in certain areas of the islands, namely on the northeastern peninsula of Tenerife.

Gaunche mummy

As the years of exploration and New World plundering waned during the 18th and 19th centuries, a new breed of explorers began to arrive on the islands, drawn not by the search for riches on the far side of the Atlantic, but by the allure of the archipelago's natural wealth which, in its pristine and isolated nature, has been said to rival that of the Galapagos Islands. The significance of the Canaries' unique subtropical Atlantic position, coupled with its favorable weather conditions, cannot be understated; the one shielded it from the ecological devastation wrought by expanding icecaps to the north in Europe and expanding desertification to the east in North Africa, while the other both promoted and sustained rare flora and fauna like the evergreen laurel forests that had become extinct on the neighboring continents due to the titanic climatic changes they experienced.

Naturalists found in the Canary Islands a botanical paradise, a haven for over 600 native species, including the mythical dragon tree, a variety of endemic birds and one species of giant lizard capable of growing up to six feet long. Today, with four of Spain's 12 national parks on the islands accounting for some 35% of their total land mass, sustaining this wondrous natural environment is a reasonable ambition despite the steady growth of tourism.

The Canaries Today

Somewhere around eight million tourists visit the islands each year, though their distribution is decidedly lopsided; the most populous island of Gran Canaria and the largest island of Tenerife, both with the tourism infrastructure and the widest variety of micro-climates, receive the brunt of the annual holiday traffic. Islands like Gomera, or Lanzarote, with its sparse volcanic landscape devoid of all but the hardiest greenery, receive far fewer visitors throughout the year and, in many cases, remain empty, save for the local populations strewn around miles of empty, sandy beaches.

What to See & Do

In most cases travelers begin their trip here on one of the two most popular islands and, if they want, use the ferry boats to reach the smaller islands for short day-excursions. While Gran Canaria and Tenerife offer the widest array of tourist entertainment and accommodations, each has beautiful and largely unspoiled natural areas just a short drive from the developed centers of activity. Scuba diving is popular in places around the islands, as is surfing and windsurfing. And each offers an extensive and varied network of hiking paths which are most frequented and best maintained within and around the four national parks.

Next page