Published by Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

1930 and renewed 1958 by Rockwell Kent

Reprinted by arrangement with The Rockwell Kent Legacies

Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT, 1978

First paperback edition 1996

Foreword to 1996 edition 1996 by Edward Hoagland

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3

CIP data appear at the end of the book

ISBN13: 9780819552921

FOREWORD

On Rockwell Kent

Edward Hoagland

LIKE JACK LONDON, George Catlin, Frederick Churchand like John Ledyard, William Bartram, John James Audubon, John Muir, Herman Melville, Stephen Crane (one could go on naming others, from Clarence King to Ernest Hemingway or Jack Kerouac)the artist-memoirist Rockwell Kent was a caroming American who drew his subject matter, inspiration, and credentials from his risky and impromptu travels. He believed in impulse, and flourished during the Roaring Twenties. In fact, he thrived in the so-called Roaring Forties, toothose wild latitudes of Tierra del Fuego to which an adventurous sea voyage carried him in 1922. Man is, after all, as Kent said, less entity than consequence and his being is but a derivation of a less subjective world, a synthesis of what he calls the elements. Mans very spirit is a sublimation of cosmic energy and worships it as God.

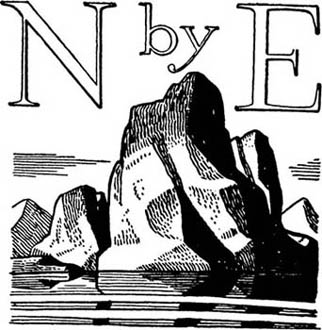

This compact bit of Transcendentalism is from N by E, Kents journal of his first trip to, and shipwreck on the shores of, Greenland, published in 1930. He was a stunning landscape and seascape painter as well as, for his time, a limber, nonpareil book illustrator, specializing in such picaresque, imperishable epics as Candide, Moby Dick, Canterbury Tales, Boccaccios Decameron, Beowulf, Paul Bunyans saga, and that of the Icelandic hero Gisli. Indeed, as though doodling, he sat one day in the office of Bennett Cerf, Random Houses cofounder, and sketched the colophon that all Random House books continue to bear. The Modern Librarys logo, a stylish Torchbearer, is also his. And for Harold Guinzburg, cofounder of the Viking Press, he quickly dashed off Vikings Viking ship. (Guinzburg had planned to call his publishing house the Half Moon Press, after Henry Hudsons ship, but the panache of the nautical Vikings, as conceived by Kent, changed his mind.)

Rockwell Kent was a figure in bon vivant and bohemian circles in the Twenties. Always busy, he drew visual bibelots for Frank Crowninshields Vanity Fair magazine, Rolls Royce ads, and simulacra of unbuilt buildings for a tony architectural firm. But he would dart off inopportunely to the Strait of Magellan, or Resurrection Bay in Alaska, or to the headlands of Newfoundland, or the west coast of Ireland, or the Alpes-Maritimes. He was not a narrow careerist, and had missed, for example, the famous Armory Show of 1913 because he had been working in Winona, Minnesota, while it was being organized. His interludes of derring-do, often in subpolar regions where he seemed to put himself in harms way for the purposes of allegory, cut into commercial jobs but ultimately furnished him with successful books like Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska (1920) and Voyaging: Southward from the Strait of Magellan (1924), and, more important, with the kinetic geometries of many trenchant paintings. If you look at the extraordinary faces he lent to Chaucer, Melville, and other master writers (Whitman, Goethe, Voltaire, Shakespearehe was game to tackle anybody), a number of them surely were engendered in the back of beyond. But he also drew the gentler shapes of Mount Equinox, Vermont, Whiteface Mountain in the Adirondacks, and Monhegan Island, ten miles off the coast of Maineplaces where hed sought to live in peace and quiet with one of his wives for a spell, until his engines of internal combustion accelerated again.

N by E, published when Kent was forty-eight and at the top of his form, is the reconstructed diary of an improvised sail in a yacht called Direction (he disliked the name as needlessly provocative) from Nova Scotia to Greenland in midsummer, 1929. He returned for a more intensive tussle with Greenlands glacial grandeur and Eskimo society, producing another book, called Salamina (1935) after his mistress and kifak housekeeper in the village of Igdlorssuit, where he settled blithely for a while. When his then-wife, Frances, arrived from America, Salamina moved next door. A second time he came back, bringing along his thirteen-year-old son, Gordon, reconnecting with Salamina, and driving a dogteam out to promontories where he could pitch a tent and paint.

But N by E has a scary, exuberant edge. First there is the excitement of an explosion of genuine pelagic perils, hairsbreadth escapes, and goofy errors. Finally the author, with his exasperatingly mismatched pickup companions, both less than half his age, comes a cropper in Karajok Fjord, thankful that hes once again survived to tell his tale. Their fools luck had run out after crossing Davis Strait. See me as Adam; set full blown into that pandemonium of force... on the rocks of Greenland (13233), he exults.

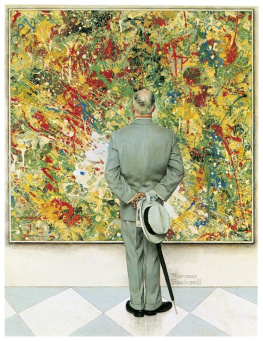

Kent was a man of remarkably incautious zest. In 1915 he and his first wife, Kathleen, with three small children, had been expelled from a sojourn in Newfoundland by the British authorities for his political pugnacity in appearing to espouse the German cause in World War I. Late in life, on the other hand, his reputation suffered grievously because of his tangles as a leftist with Senator Joseph McCarthy and the State Department in the 1950s. His right to a passport was rescinded, instigating a fight he carried to the Supreme Court, which intervened in 1958 to restore it by a five to four decision written by Justice William O. Douglas. Politically, he was credulous, dogmatic, and combative as well as idealistic, and one can bridle at his tolerance for Stalinism. But the result was that his work almost ceased to be exhibited, and by 1960 he felt constrained to donate a core of eighty paintings and more than eight hundred prints and drawings to the Soviet Union, where they were at least preserved in such museums as the Hermitage. Nine years later his house burned down. The swing from 1930s-style Art Deco and dramatic realism to abstract expressionism had already put him out of fashion. Nor would feminism revive him, as it did his fellow wilderness buff, Georgia OKeeffe. George Bellows, Edward Hopper, and Jonas Lie are other contemporaries whose vision may have intersected a bit with his, and his friendships ranged from Marsden Hartley to Paul Robeson, a fellow radical whose passport was only restored after Kents lawsuit won the right of free travel for U.S. citizens from the High Court.

Kent was the sort of adventurer who lives to be eighty-nine. Born in 1882, he won the Lenin Peace Prize in 1967 and was able to tweak the choler of the redbaiters yet again by donating part of this scandalous swag to the suffering women and children of the South Vietnamese Liberation Front. He indulged in several junkets to Russia and had a few domestic champions, but generally he was jettisoned by the art world and denied the acquaintanceship among Manhattans cognoscenti that he might otherwise have enjoyed. Fortunately, spending his old age in exile in the north woods was not a great hardship for him. His versatility and his affinity for nature as usual served him well. He had a pacemaker installed toward the end, was bothered by deafness, and died of a stroke.

Next page