Captive Insurance

in Plain English

F. Hale Stewart, JD. LL.M.

CAPTIVE INSURANCE IN PLAIN ENGLISH

Copyright 2017 Hale Stewart.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

iUniverse

1663 Liberty Drive

Bloomington, IN 47403

www.iuniverse.com

1-800-Authors (1-800-288-4677)

Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

Any people depicted in stock imagery provided by Thinkstock are models, and such images are being used for illustrative purposes only.

Certain stock imagery Thinkstock.

ISBN: 978-1-5320-3571-5 (sc)

ISBN: 978-1-5320-3572-2 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017916089

iUniverse rev. date: 11/15/2017

CONTENTS

My first book on captives is US Captive Insurance Law . It is meant for professionals in the captive insurance industry. Its not for the layperson who wants a basic understanding of what captive insurance is and how it works.

Thats where Captive Insurance in Plain English comes in. Its deliberately brief; you should be able to read it in one or two sittings. Most importantly, it contains the information you need to make a decision about whether or not you should form a captive insurer for your business.

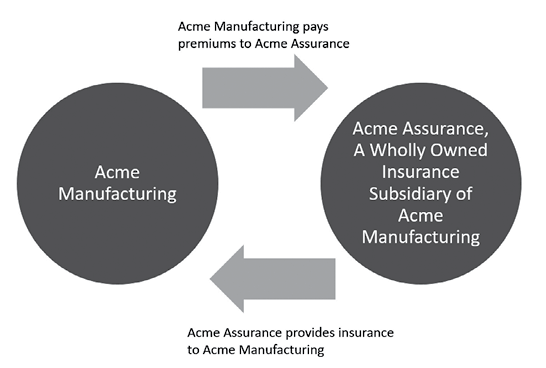

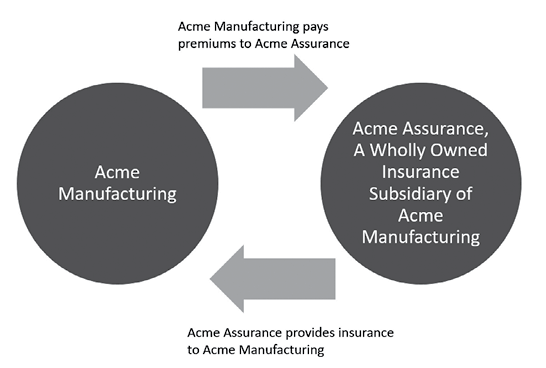

Before we begin, let me provide a few working definitions and some general background. A captive insurance company or captive -- is an insurance subsidiary. For example, Acme Manufacturing is a corporation that makes widgets. Acme Manufacturing forms Acme Assurance which sells various types of insurance to Acme Manufacturing. Heres a picture of the transaction:

I first encountered captive insurance in graduate school when I read the UPS case for a course on offshore financial centers. This decision that UPS won on appeal -- was the last in a long line of unsuccessful IRS challenges to various captive insurance arrangements. Throughout the litigation, the government argued that various insurance subsidiaries werent valid insurance companies for tax purposes. The stakes were high: taxpayers had deducted a large amount of premiums they paid to their captives. Had they lost, they would have faced a large back tax bill. Thankfully for us, the IRS lost a large number of these cases starting in the late 1980s; the UPS case was no different.

The decision had a profound impact on me, largely because of my professional background. Before I was a lawyer I was a bond broker where I sold bonds to insurance companies. These companies when run properly are very profitable, offering owners a tremendous business opportunity.

In the first chapter, I cover not only the reason why companies started forming captives but also the IRS unsuccessful attempts to challenge this transaction. This history is vital: it explains both the appropriate business reasons for forming a captive and how to properly structure the transaction. In my second chapter, I explain the legal definition of insurance and insurance company -- which your captive will have to comply with. The third chapter explains insurance policies -- more specifically, it addresses some of the policies your captive will sell to your company. And finally, chapter four walks through the captive formation and management process so that youll know what to expect when youre putting your captive together along with working with your captive manager after its formed.

So, lets get started!

CHAPTER 1

A History Lesson or Why Did Companies Start Doing This?

Captive insurance didnt just happen. Negative developments in the insurance markets such as expensive insurance policies or a complete absence of any insurance coverage for specific risks -- forced companies to form insurance subsidiaries. But the IRS did not believe these were real insurers leading to a 30-year conflict between the Service and taxpayers. Although the service had five early victories, they lost most of the remaining cases that had properly structured insurance companies.

Its vitally important to understand this history and the specific reasons why the IRS lost subsequent cases. Taxpayers victories illustrate structures that are now commonly used in the captive ma rket.

Round One: The Flood Plane Cases

Cincinnati, Ohio, where I was born and raised, is the quintessential Midwestern city. When I was growing up, its population was under 500,000. But its smaller size belied its importance. Cincinnati was not only home to several large S&P 500 companies like Proctor and Gamble, Kroger, and Foleys (which was eventually purchased by Macys), but was also home to a robust service sector.

Cincinnati is also a river city. It started and thrived because of its location on the Ohio River. As in Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Kansas City and New Orleans, river transportation was the citys primary source of business development and expansion. I also vividly remember several times when the Ohio River flooded, causing damage and other problems.

We also have waterways to thank for the first two fact patterns that led to the creation of captive insurance companies. Both Consumers Oil owned property located next to a river (the former in New Jersey and the latter in Kansas City). Both rivers flooded in the 1950s, driving commercial carriers out of the insurance market, forcing both companies to form an insurance company to provide flood insurance. One survived an IRS challenge and the other did not. The histories of these two programs provides a template for what to do and what not to do when setting up a captive pro gram.

Consumers Oil formed a trust that only sold insurance to one entity Consumers Oil. In contrast, Weber Paper formed an insurance company with other Kansas City companies for the purpose of insuring themselves. The Missouri and Kansas insurance departments formally licensed the insurer in their respective states. Several plan participants applied for and received a Private Letter Ruling from the IRS to make sure the federal government would recognize the transaction as insurance for tax purposes. Despite this apparent inoculation against IRS attack, the Service subsequently challenged the validity of the insurance company just as they did with Consumers Oils trust structure.

The courts ruled Consumers Oils trust wasnt an insurance company while Weber Papers was. Key to each decision was the number of insureds. Because the Consumers Oil trust only sold insurance to one insured, the court ruled the trust was an accounting reserve. In contrast, the insurer in the Weber Paper case sold and provided insurance to a group of companies with a similar risk. This larger number of companies insured by the captive helped to create insurance.

Round Two: the IRS Wins a Few and Then Loses More Than a Few

In the early 1960s, the IRS formally announced they would not follow the Weber Paper decision. While this might seem presumptuous (or aggravating, depending on your point of view), its allowed in a common law system, where anyone may challenge a ruling if they have a good faith belief in the validity of their position.

Next page