Acknowledgements

MY THANKS TO THOSE CHINESE who have been so welcoming to me in my travels, particularly professors Li Qi and Wang Ye of Xian Jiaotong University, their families, and their many friendly graduate students, especially Li Pei, Zhang Yu and their families, my sometime driver Andrew Li Jiang and whatever anonymous replacements he periodically rustled up to drive us to the middle of nowhere. My wife Kati and son Alexander have been enthusiastic travelling companions and occasional guinea pigs, uncomplaining about experiments in dining or trips to distant, dusty temples. In Finland, the Mki-Kuutti family, particularly Matias, Raija and Seija, and Ritva Parkkonen kindly helped out with housework and childminding, in order to help me find the time to finish this book.

Back in Britain, the staff of Haus Publishing has been flexible and accommodating. Ilse and Barbara Schwepcke commissioned this book, Harry Hall looked the other way when I wanted two more months to write, and Ellie Shillito kept things on track from manuscript delivery to the finished article. Andrew Deacon commented on an early draft of the manuscript and hunted for errors, although any that remain are sure to be mine.

The Invention of the Silk Road

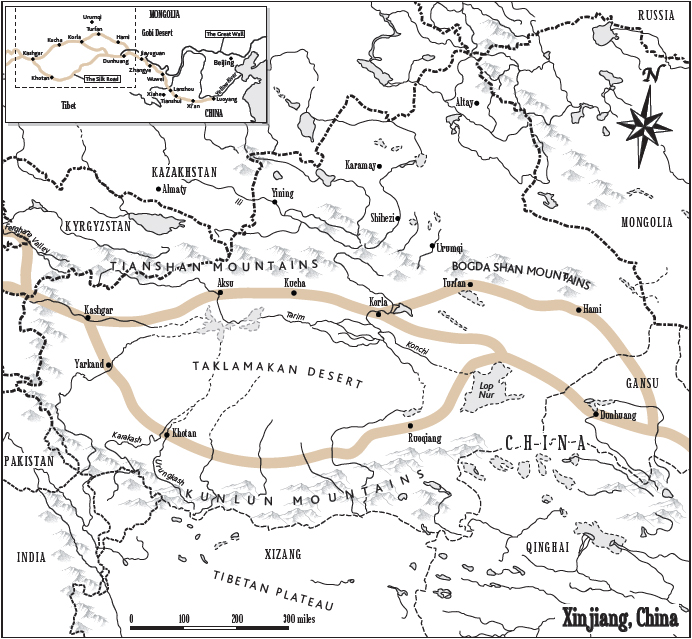

THE SILK ROAD is a modern idea, dating only from 1877 when Ferdinand von Richthofen, uncle of the more famous Red Baron, published a multi-part atlas of China. His first volume included a map of Die Seidenstrasse, Richthofens term for the route that, he assumed, Chinese silk had taken towards the Greco-Roman world in antiquity. Key points included the trading centres of Samarkand and Xian (formerly known as Changan), from which branches would shoot off in multiple directions. Between those two towns the route was simpler, and limited to only a couple of branches that traversed the west Chinese region known today as Xinjiang.

Richthofens term had a romance to it, a sense of mystery and wonder that proved infectious. The term Silk Road is now in widespread use, even in the regions through which the trade passed. In Chinese, it is translated as Sichou zhi Lu, an oddly classical construction that makes it sound like some ancient term, and not something knocked up by a German geographer only 150 years ago. In Uyghur, a Turkic language spoken by many natives of the region, its Yipek Yoli, connoting, as in other languages, a solid, physical road to the exotic west.

Just to confuse matters, there is a concrete, identifiable Silk Road today. It is the name of a motorway that curves along the northern reaches of the Taklamakan Desert, with signage helpfully written in English so that tourists can feel that they are getting somewhere. But none of the travellers on the historical Silk Road ever used that term. Only a handful of men and women ever travelled its entire length. For most of the participants in the trade route, the road, if there was even a real road, was only to the next town or oasis. Artefacts and articles might meander along the route from China to the Mediterranean, but only in stops and starts, traded back and forth, buffeted by changing conditions and markets, until they suddenly tumbled out at the far end to the bafflement of their final buyers.

In fact, there was never a single line, even in Richthofens original atlas he spoke of a single Silk Road, but also referred to the route in the plural as Silk Roads. Many writers prefer the term Silk Routes in order to point out that there is no single identifiable road, but a number of well-travelled paths and tracks, worn by camel caravans over the years. Towns, of course, were places where caravans of camel-drovers could grab new supplies, rest a little and graze their animals. But the pathways between them fluctuated on the basis of weather, war and local politics even the towns of the Silk Road could fall in and out of favour, left high and dry by the ebb and flow of trade and by drastic changes in water tables or river courses.

Richthofens classical education had exposed him to the writings of the Roman author Pliny the Elder, who complained about all the coins being sent east to pay for silk, and it seems that this was what led Richthofen to draw his line joining China to the Mediterranean. Nor was the traffic all in a single direction. Much of the silk that headed west from China was intended for the Ferghana Valley in what is now Uzbekistan, where it was traded for the regions highly prized horses. No coins of the Roman republic or early empire have ever been found in China. Those few Byzantine coins that made it all the way along the Silk Road were of little use at its terminus, except as odd souvenirs. Far more Roman coins, in fact, made their way to India, and in such quantities that they were sometimes repurposed as local currency. In fact, much of the material that Richthofen assumed to have reached Rome down his Silk Road may have instead trickled south from Xinjiang, through what is now India and Pakistan, and then by sea to Roman Egypt.

The same trade routes carried glass and gemstones, musical instruments and slaves, medicinal herbs and strange spices. As early as AD 331, princes of Ferghana were sending gifts of cotton east to the rulers of north China. In the distant past, the same routes had carried the ancestor of the modern apple westward from central Asia, and the bulbs of a flower that the Persians called dulband (turban), and which entered medieval Latin as tulipa. However, silk seems to have been the commodity most likely to travel the entire length from east to west. This was partly because of its value at the western end, but also because of its portability and durability. Silk, in both woven and raw form, was a major form of currency for certain early Chinese dynasties, far more convenient than mere coins. It was transported, usually on camels, west from China to the forbidding deserts and steppes as bribes, gifts or soldiers salaries, depending on the political situation among the border tribes. Those groups, in turn, would pass the silk on, with much of it continuing further west as payment for livestock or luxuries. Valerie Hansen, in