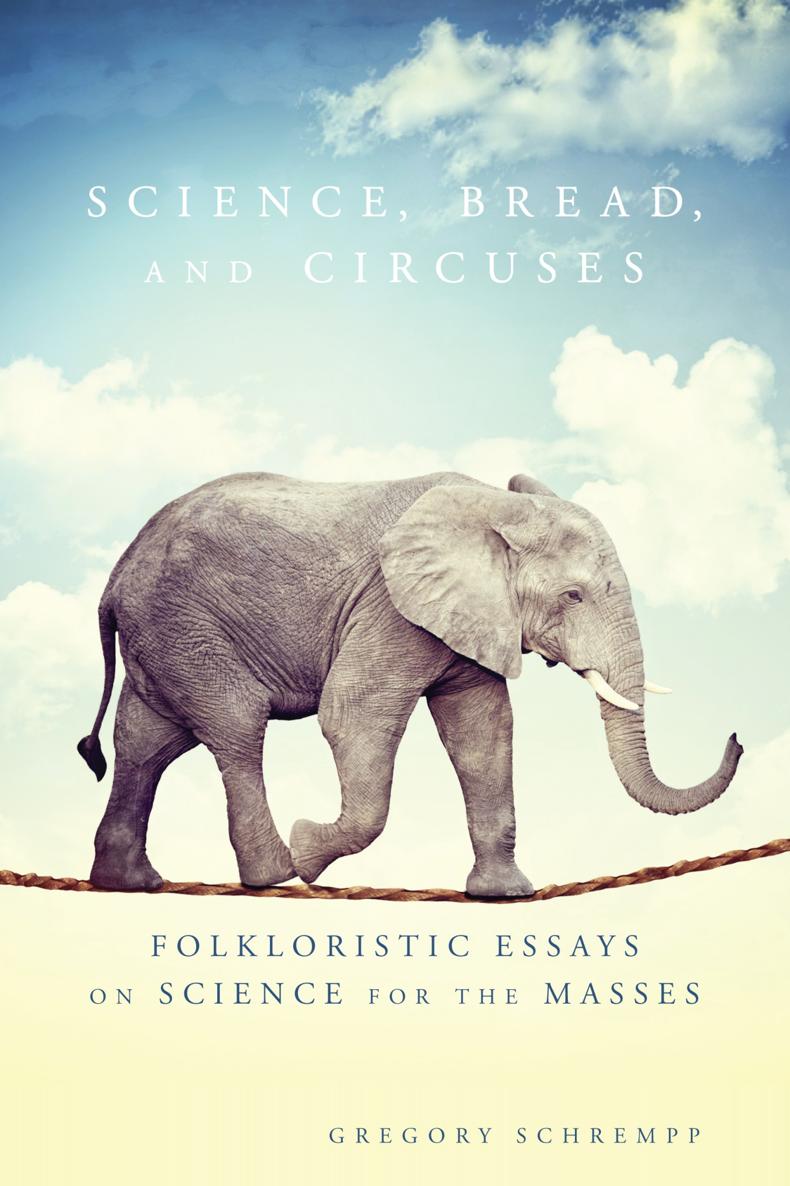

Science, Bread, and Circuses

Folkloristic Essays on Science for the Masses

Gregory Schrempp

UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Logan

2014 by the University Press of Colorado

Published by Utah State University Press

An imprint of University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of The Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.481992

ISBN: 978-0-87421-969-2 (paper)

ISBN: 978-0-87421-970-8 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schrempp, Gregory Allen, 1950

Science, bread, and circuses : folkloristic essays on science for the masses / Gregory Schrempp.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-87421-969-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-0-87421-970-8 (ebook)

1. Science in popular culture. 2. Folklore. 3. Legends. 4. Myths. I. Title.

Q172.5.P65S45 2014

303.48'3dc23

2014001149

The material in chapter 1 was published in earlier form as Formulas of Conversion: Proverbial Approaches to Technological and Scientific Exposition (Midwestern Folklore 31:513) and is used by permission of the Hoosier Folklore Society.

The material in chapter 2 was published in earlier form as Canonizing Creativity: Folkloric Patterns in Motivational Speaking (Midwestern Folklore 33:3743) and is used by permission of the Hoosier Folklore Society.

The material in chapter 4 was published in earlier form as Taking the Dawkins Challenge, or, The Dark Side of the Meme (Journal of Folklore Research 46:91100) and is used by permission of Indiana University Press.

Cover illustration: gualtiero boffi / Shutterstock

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the many students and colleagues who provided thoughtful and helpful responses to the ideas presented in this book. I am especially thankful to Ronald Baker, Karen Duffy, William Hansen, Wally Hooper, Jens Lund, Moira Marsh, Nan McEntire, Joseph Nagy, Elliott Oring, Daniel Peretti, Marshall Sahlins, Bill Schrempp, George Stocking, and Kyoim Yun. The UCLA Film and Television Archive provided assistance with the film research. I am grateful to Michael Spooner and the staff of Utah State University Press/University Press of Colorado for their support and help; reports from two anonymous readers were also very useful. My wife, Cornelia Fales, helped with every aspect of this endeavor.

Science, Bread, and Circuses

Introduction

Bread and circuses is a pejorative phrase, but who would give up either? The term folklore is often used derogatorily; but in a recent, elite university class I got no yeses to this question: would a world without urban legends be a better world? And who among us is not proud, sometimes, to merge into the masses, or at least this or that mass?

The works that most epitomize the contemporary genre of popular sciencebooks by John Barrow, Daniel Dennett, Brian Greene, or Stephen Hawkingare not read by the masses but instead by the proverbial serious reader who maintains a generalized philosophical or nerdy interest in science. The very notion of the popular is relative, begging the question, how popular? The book you are now reading, though designed to be complete in itself, is also a companion to a previous work, The Ancient Mythology of Modern Science: A Mythologist Looks (Seriously) at Popular Science Writing (). In that work I critically analyze the arguments put forward in major books by writers like those just mentioned, who form what might be termed (oxymoronically for sure) the elite of the popular science genre. What remains for consideration is a vast, variegated, fascinating landscape of science popularizing. It would be a great mistake to limit ones gaze to the elite realm, which forms only one small part of the venture.

The strategies of science popularizingor science domesticationthat I focus on in the chapters in this book have all been selected with a folklorists eye for traditional gestures and genres that have always radiated power and appeal; these include major oral narrative genres (myth, epic, legend, folktale) as well as other orally inspired forms (such as proverb, sermon, and local religious visions and rituals/spectacles). has accomplished in her study of folkloric patterns in contemporary self-help literature, although my study will consider a wider range of artifacts, for books are only one among many media of science popularizing I will consider. Dolbys analysis might be seen, in turn, as a new development within a longer scholarly tradition, advocated by Richard Dorson, among others, of identifying continuities of folklore in realms lying outside traditional oral circulation. My specific concern within this longer tradition will be to identify folkloric inspiration, form, and process in the popular exposition and promotion of science.

The masses is a notoriously difficult concept, one I use loosely, evocatively, and provocatively. Three major qualifications should be kept in mind throughout. The first is that the notion of the masses is fraught with moral, aesthetic, and political ambivalence, as well as intrinsic reversibility (as are its opposites, the elite, the sophisticated). The masses are low in status but also the basis of all power and often rhapsodized with populist sentiment. The second point is illustrated by a quirk in the term itself, namely, that the masses is (are?) plural, in a sense contradicting the direction in which the term seems to be headedthat is, a merging of members into a unitary heap. It will quickly become apparent that we are dealing with more than one mass (and it is probably fair to say that all human beings, if not all living things, belong to a plurality of lumping categories). In most cases we are dealing with a polarity straddling a vast borderland. What I mean by the masses in this book can most safely be expressed privatively: the works of science popularizing considered here are directed toward audiences whose members lie mostly outside the first circle of devotees of elite popular science literature.

The third point is a combination of the first two: specifically, that some masses are in another respect also elites. Certain artists and critics, most famously Leo Tolstoy, conclude that the greatest art will necessarily be understandable by anyone; in other words, the highest art will necessarily be low. On this last point, consider the topic of chapter 9, British playwright Tom Stoppards Jumpers. Stoppard is among the very finest writers of dramatic dialogue, backed by a distinguished national/cultural theater tradition; yet much of the dialogue of this play, and certainly the genre-frame, resemble the detective novel, a socially unpretentious literary form radiating the broadest popular appeal. Some of the protagonists are university philosophers, but the action takes place around their activities as amateur acrobats (jumpers); and the play opens at a party in which a scantily clad woman swings trapeze-like back and forth above a partying crowda sort of circus without a tent. Stoppards plot also directs attention toward a mission to explore the moon. The mission is made possible by sophisticated technology that, however, also makes possible the real-time viewing of the chosen few space explorers by mass audiences. Moreover, Stoppards depiction of the technological conquest is punctuated by old, popular romantic songs about the newly demythologized moon.