Bread Science

The Chemistry and Craft of Making Bread

Emily Buehler

Two Blue Books, Hillsborough, North Carolina

BREAD SCIENCE

The Chemistry and Craft of Making Bread

by Emily Buehler

Published by:

Two Blue Books

P.O. Box 1285

Hillsborough NC 27278 U.S.A.

www.twobluebooks.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.

Copyright 2006 by Emily Buehler

Second printing 2009

Electronic version 2014

First print edition ISBN-10: 0-9778068-0-4

First print edition ISBN-13: 978-0-9778068-0-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2006906646

Electronic version ISBN: 978-0-9778068-1-2

Contents

flour, yeast, water, salt

what they are, how to mix them

Units and conversion factors

(print books)

Note to the reader on the organization of this book

I have set u p Bread Scienc e to be as much like a reference book as possible, enabling readers to open to a section of interest without needing to read the whole book. Chapters three through seven, which describe the process of bread-making, go in chronological order, to aid beginners . Bread Scienc e focuses on learning about the process of bread-making instead of individual recipes. In that sense it is not a traditional cookbookit contains only basic recipes intended to illustrate the concepts discussed.

I dedicated a separate chapter to bread science so as not to confuse readers trying to focus on the practical aspects of bread-making in later chapters. Thus, chapter two contains a more complete description of the different aspects of science occurring in dough. This science is referred to in relevant places throughout the book, but with less detail. I have included all scientific terms in the glossary.

In chapter two, references are given to research papers. Wherever possible, I have referenced the source documenting the original research, not just a paper that refers to it. This was not always possible: some papers were unavailable or not written in English. The bibliography lists the major papers on each aspect of bread science and is a good place to begin if you would like to read more.

Some readers may find chapter two daunting or a bit overwhelming. If you are eager to get to bread-making, skip chapter two for now and dive right in to the practical chapters. You can return to the science later, perhaps while you are munching on a freshly-baked slice of bread.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to everyone who has supported me during the past four years while I wrote this book.

Thank you to Casey Perry for starting bread class with me and helping write the original bread class manual, where it all began.

Thank you to the public universities of North Carolina for keeping their library doors open to me. Without access to the information available there, I would not have been able to write this book.

Thank you to everyone who read the manuscript: Cat Moleski, Cari Abell, Bridget Pool, Mary Bratsch, Maria Mauceri, Tema Larter, and Seth Elliott.

Thank you to Mary Bratsch, the chapter six hand model extraordinaire.

Thank you to Brian Cook for answering many questions, teaching bread class with me, giving me a scale, giving me time off to write, for his brief stint as a hand model, and for all the rides to the NC State library.

Thank you to Jaso Phillips for help with all things computerPDFs, halftones, hard drive space, burning CDs, writing html.... Tech support would be a ridiculous understatement.

Thank you to Maria Mauceri for the photo shoot.

Thank you to Ben Horner for the use of your printer.

Thank you to Bill Koeb for the last minute help with InDesign and PageMaker.

Thank you to my editor, Cinnamon Fischer.

Thank you to my distribution offices, Susan and Barry Buehler.

Finally, a special thanks to everyone who helped me after the book was printed. I am sorry not to thank you by name. Youll be in the second edition!

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Susan and Barry Buehler, the perfect combination of art and science.

Introduction

The obvious way to make bread is to find a recipe in a book and follow it. Chances are it will work well enough, but making bread this way confines the baker to one recipe, gives him or her no understanding of how to fix problems that arise, and perpetuates the myth that he or she needs a good recipe to begin with. In short, following a recipe is not an empowering way to make bread.

The alternative method explored in this book is more akin to what our ancestors might have done, working with basic recipes to learn about the process of bread-making, with the added benefit of decades of scientific research enabling us to understand the inner workings of the process. Think of the method as starting from the beginningeach time you make dough you see what happens to it and learn something new about the process. The information provided in this book will help you learn faster and understand how and why bread works. From there, any recipe will be conquerable.

Reading about bread will not be enough though; the only way to get to know dough and bread is to have your hands in itpractice. Do not be intimidatedmistakes and failures are just opportunities to learn. (Besides, messed up bread often still tastes good!) Take data when mixing your doughuse the data sheet in chapter four. Remember what the dough feels like. Write notes for next time in order to remember what to do the same way or differently.

Good bread is not the result of one brilliant mind; it came about by trial-and-error, over the centuries. And it was done by ordinary people; it does not require special talents or an advanced degree. Re-learning the process from the beginning is surprisingly simple. In this day, making bread by hand might seem like a lost art, but it remains accessible to anyone who wishes to try it.

Chapter 1: Bread-making Basics

This chapter contains information on some basic concepts in bread-making that will help you get off to a good start.

1.1 The basic bread recipe

The basic bread recipe is the lowest common denominator of bread recipesthe simplest one possible. It gives new bread makers a simple recipe to use and illustrates that all recipes are derived from the same place. There is no secret to themthey all have basically the same percentages of water, yeast, and salt, adjusted to account for the other ingredients. (The percentages, which may seem odd, are described in the following section, Bakers percent .)

What makes good bread is the attention given to the dough, not the recipe. This is especially true for bakers working in distinct climates. A world-famous recipe from a California bakery might need adjustment when used in the humid eastern Carolina summer with a different brand of flour and different water. Bakers make adjustments by paying attention to the doughs characteristics.

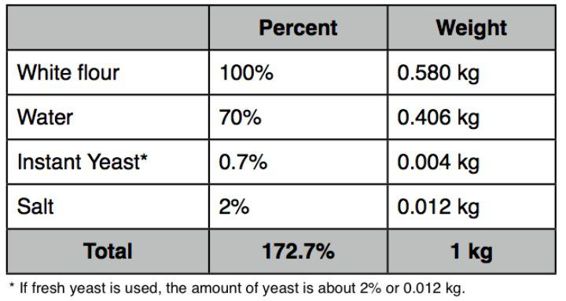

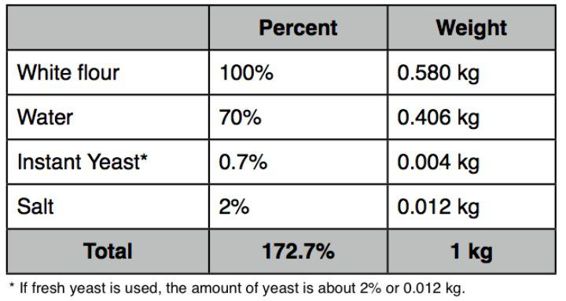

The basic bread recipe for a one kilogram (about two pound) loaf of bread is

This recipe is converted to cup and teaspoon measures in the following section, Weight versus volume.

If you slap together this recipe, do not knead it enough, stick it in the refrigerator overnight because you are too tired to bake it, and then put it in a conventional oven without knowing if it is ready to bake, you will still produce bread that tastes good! From there, you can use your knowledge of bread-making to improve the resultto get more volume (i.e., bigger bread) or a nicer-looking crust, for example. The important thing is just to get started!

Next page