ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My greatest debts are owed to those who permitted me to study their labs. Michael Hecht and Ron Weiss shared their time, space, and thoughts with me, exhibiting both generosity and curiosity. Many of their students and postdocs followed suit. Since I have anonymized those who were more vulnerably situated, I regret that I can acknowledge their generosity and grace only collectively. It goes without saying that this project would never have gotten off the ground, much less sustained flight for so many years, without this group of wonderful interlocutors.

Princeton University proved both an interesting site and a convivial home in which to give this project its initial form. Abdellah Hammoudis intellectual guidance was formative in ways that both permeate and exceed this book. Jim Boon, Rena Lederman, and Larry Rosen read, listened, taught, and inspired. Mentoring at Princeton was wonderfully collective. Joo Biehl, John Borneman, Lisa Davis, Carol Greenhouse, Alan Mann, Carolyn Rouse, and the late Isabelle Clark-Deces helped make Princetons anthropology department the vibrant place that it was during my years there. Completion of a very early version of this work was supported by Princeton Universitys Woodrow Wilson Society.

I am exceedingly grateful to colleagues at Washington University in St. Louis for supporting and engaging with this work at various stages. Among them, John Bowen has proved an invaluable mentor and interlocutor. Beyond the anthropology department, colleagues from across campus have made life at the university much more interesting and fulfilling. A special thank-you to participants in the Philosophy of Science Reading Group, Ethnographic Theory Workshop, and Social Studies of Institutions Group for offering consistent intellectual enrichment and for engaging with several portions of this work.

This book has benefited from conversations with many colleagues, friends, and mentors over many years, including Mark Alford, Gaymon Bennett, Peter Benson, Venus Bivar, Leo Coleman, Carl Craver, Tili Boon Cuill, Monica Eppinger, Bret Gustafson, Nathan Ha, Ronnie Halevy, Janet Hine, Helen Human, Jean Hunleth, Peter Kurie, Rebecca Lester, Richard Martin, Stephanie McClure, Paige McGinley, Claire Nicholas, Bruce ONeill, Shanti Parikh, Anthony Petro, E. A. Quinn, Tobias Rees, Annelise Riles, Mark Robinson, Elizabeth Schechter, Lihong Shi, Larry Snyder, Priscilla Song, Anthony Stavrianakis, Glenn Stone, Kedron Thomas, Erica Weiss, Ian Whitmarsh, Mo Lin Yee, and Carol Zanca. I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Paul Rabinow, without whom this book (not to mention the trajectory that begot it) would be unimaginable.

At Cornell University Press, Dominic Boyer and Jim Lance helped make the publishing experience a truly pleasant one.

I have been immensely lucky on the family front. My deepest thanks to Paulo, Mina, Leo, Hana, Meir, and Ishai for all of the love and humor that sustained me throughout.

An earlier version of chapter 2 appeared as Ignoring Complexity: Epistemic Wagers and Knowledge Practices among Synthetic Biologists, Science, Technology, & Human Values 41, no. 5 (2016): 899921, doi:10.1177/0162243916650976.

INTRODUCTION

In 2004, J. Craig Venter and Daniel Cohen, two famed geneticists, published a review that began with a declaration: If the 20th century was the century of physics, the 21st century will be the century of biology. A self-fashioned genomics maverick, Venter had headed the private effort to sequence the human genome at Celera Genomics, competing with the publicly funded Human Genome Project. The sequence was, we recall, likened to the Holy Grail. It was expected to answer a lot of questions about living things, to explain differences and provide drug targets, to allow a glimpse into our own individual biological futures and our collective evolutionary histories. The buildup was not quite matched by the pace of discovery in the wake of the sequencing project. Many biotech companies formed and dissolved, their research agendas and business plans unwieldy in the face of anxious investors, recalcitrant genomes, and mountains of sequence information.

Sequencing genomes was what had gained Venter his considerable fame, yet it is not the primary endeavor to which he has hitched the destiny of mankind. In 2004, the field of synthetic biologyan umbrella term for attempts to design and assemble new life-formswas just gaining speed. Venter was himself mounting an impressive effort to make headway in this new domain through research at the J. Craig Venter Institute. The activities linked together under the heading synthetic biology have always been heterogeneous, but one underlying theme uniting many of them is a bottom-up approach to the design and construction of synthetic organisms. Elaborate a biological toolkit. Forget, black-box, or defer the complexity. Build a better, simpler life.

Though synthetic biology got its start in the early 2000s, it wasnt until 2010 that Venter and his institute managed to reach a major milestone in this new pursuit. In June of that year, Venters team announced the successful synthesis of a very simple life-form: scientists at the institute had stitched together a synthetic genome almost identical to that of the bacterium Mycoplasma genitalium and transplanted it into a host cell that expressed the donor DNA. In countless newspapers and journals, the construction of this being was tallied as a win for the emergent field. More a proof-of-concept than a technological breakthrough, the bacterial hybrid nonetheless provided an occasion for scientists and news agencies to hail the arrival of designer synthetic organisms that will someday eat environmental contaminants, produce fuel, provide shelter, and even search for and destroy diseased cells in our bodies.

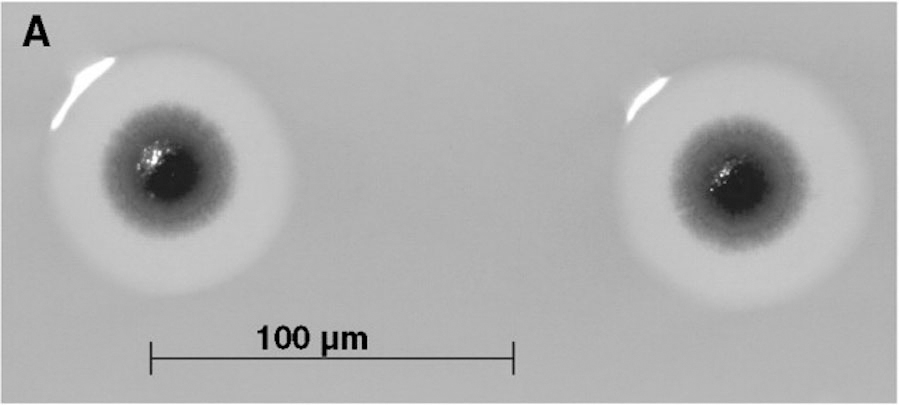

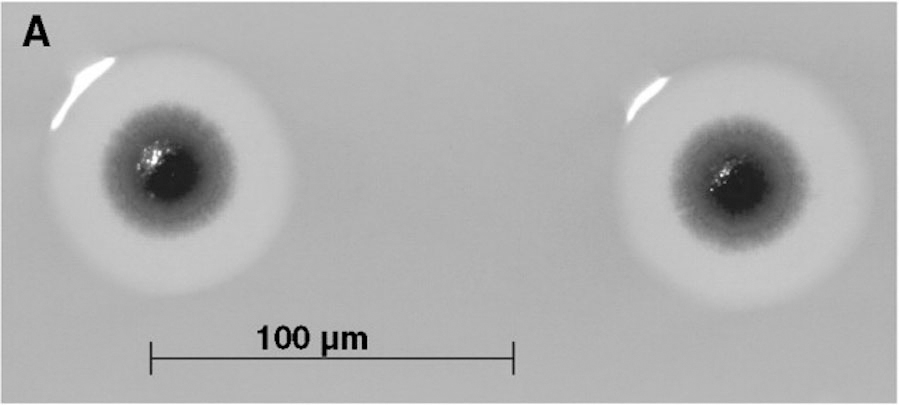

Many of the articles announcing the successful synthesis also ran an accompanying photo of a pair of these new life-forms, slightly asymmetrically situated on a fleshy orange background, resembling two eyes peering back at the reader as though through bright-blue irises.

What to make of this reciprocal gaze? In a piece on the contemporary biosciences, written in the late 1990s as the Human Genome Project was gaining speed, Paul Rabinow noted that the unanticipated overlap between the human genome and gene sequences present in other animals, shuffled and recombined, lent a certain prescience to Rimbauds cryptic prophecy that the man of the future will be filled with animals. Yet, just as the human seems to disaggregate into an evolutionary history of recombinable bits of animality, organisms themselves increasingly become artifacts of human design. We might want to ask, then, in response to Rimbauds prophecy, with what exactly will these animals themselves be filled?

From Daniel G. Gibson et al., Creation of a Bacterial Cell Controlled by a Chemically Synthesized Genome, Science 329, no. 5987 (2010): 5256. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

From certain angles, this question seems relatively new. Humans have long attempted to situate themselves in the order of things by reference to the mirror of nature, a nature that also peeks out from within. So what happens when biotechnology remakes the natural world? The ensnaring, expressionless stare of these two eyes captures something of the seeming contemporary existential predicament of culture seen through the mirror of culture (in cell culture, no less). In his writings on the frontiers and borders of the biosciences where the limits of life are encountered, Stefan Helmreich argues that, in the age of biotechnology, genomics, cloning, genetically modified food, and reproductive technology, when human enterprise rescripts and reengineers biotic material, a founding function for nature is not so easily discernible. Culture and nature no longer stand in relation of figure to ground. Life forms cannot unproblematically anchor forms of life.