AFRICAN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDIES

OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Volume 31

THE SOCIAL ORGANISATION OF THE LO WIILI

THE SOCIAL ORGANISATION OF

THE LO WIILI

JACK GOODY

First published in 1956 by Her Majestys Stationery Office, second edition published in 1967 by Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

This edition first published in 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1967 International African Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-8153-8713-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48813-9 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-58480-8 (Volume 31) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-50570-6 (Volume 31) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

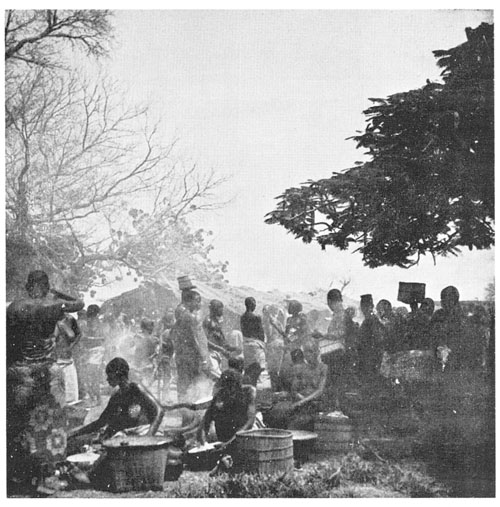

Frontispiece

A M ARKET

Women cooking food for sale

The Social Organisation of the LoWiili

by

JACK GOODY

Second Edition

Published, for the

INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN INSTITUTE

by the

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1967

Contents

Oxford University Press, Ely House, London W. 1

GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON CAPE TOWN SALISBURY IBADAN NAIROBI LUSAKA ADDIS ABABA BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI LAHORE DACCA KUALA LUMPUR HONG KONG TOKYO

New matter in this edition

International African Institute 1967

First published 1956

(Her Majestys Stationery Office)

Second Edition 1967

(Oxford University Press)

Reprinted Lithographically in Great Britain by Compton Printing Ltd.

London and Aylesbury

M APS AND D IAGRAMS

T ABLES

P HOTOGRAPHS

The people described in this book occupy the north-west corner of Ghana and the adjacent areas of the Upper Volta and the Ivory Coast, which lie across the Black Volta. They are part of a belt of Dagari-speaking settlements which form a continuum both of dialect and of culture. Indeed there are even fewer distinct boundaries than among the Tallensi and their neighbours, of whom Fortes has written: there is no tribal unity among the Tallensi in the ordinarily accepted sense of this phrase. They have no fixed territorial boundaries, nor are they precisely marked off from neighbouring tribes by cultural or linguistic usages. The tribal unity of the Tallensi is, in general terms, the unity of a distinct socio-geographical region forming a segment of a greater region of similar cultural type, economic organization, and social structure. This region can be demarcated only by dynamic criteria. The Tallensi have more in common among themselves than the component segments of Tale society have with other like units outside what we have called Taleland. (1949:12).

Among the Dagari-speaking peoples, a similar situation is reflected in the complex and changing mode of identification. The actors recognise the cultural and linguistic differences that obtain in the area, the local variations that exist within a considerable degree of cultural uniformity, and refer to them by placing particular customary acts in relation to two categories, Lobi and Dagarti (Lo and Dagaa), the use of which resembles the English terms Westerners and Easterners. But the outside observer (and in some limited contexts, the locals too) needs a set of fixed, not relative, terms to guide him; indeed one of the great difficulties in the ethnography of this region is the fact that such observers invariably take these relative terms as fixed, tribal designations.

In addition to the relative directional terms, the actors also discriminate areas of cultural similarity, referring to certain features that they deem important, such as matrilineal inheritance of movables and the presence of various types of xylophone. And these areas they sometimes point to by means of other tribal designations, which are usually modifications of the basic directional terms, Lo and Dagaa. The present study is of a large dispersed settlement of LoDagaa who usually refer to themselves by the name of the locality (Birifu) but are sometimes known as the Wiili (Fr. Wil or Oul, see Labouret, 1931) or the LoWiili (Duncan-Johnstone, 2nd Lawra District Record Book, p.428, 1918). I have preferred the second of these, in order to conform to the distinction made by the actors between the inhabitants of the Birifu area (LoWiili) and their eastern neighbours around Tugu (DagaaWiili).

Given the terminological complexities, it is perhaps not surprising to find these people largely ignored in standard ethnographies, and, where not ignored, then muddled and confused. For example, Murdock (1959:79) mixes up the pagan, acephalous Wiili with the Muslim, centralized Wala, and includes the Dagari among the Grusi rather than the Mole (Mossi) speakers. The late L. Girault, regarding my scheme as too complicated, throws all the Dagari-speaking peoples of Ghana into one commodious container; linguistically, this may be reasonable, but not ethnographically. The range of social organisation requires more careful discriminators. The Reverend Father makes the same error as those English speakers who, looking from the other bank of the river, group all the inhabitants to the west under the name Lobi (Lo) and fail to appreciate both the recognized cultural differences and the relative nature of the terminology.

This complex and subtle way of referring to ones own and neighbouring settlements arises from the fact that networks of social relationships have few marked discontinuities; consequently there is no real concept of a tribe (a named cultural unit), much less of a nation (a named political one). The main unit of study is necessarily the parish (or ritual area) which usually comprises a settlement (named area of habitation); and it is the settlements of Birifu and Tom that constitute my societies. The people that Girault speaks of as Dagari (or Dagara) are the same ones that I call LoDagaba, and in this book I refer several times to the LoDagaba settlement of Tom, where I spent some nine months in 1952. Much of my subsequent work has been an attempt to study and explain the differences in the social life of these two communities, differences which, as I have said, are recognized by the actors as characteristic of the wider areas of cultural similarity I refer to as the LoWiili and the LoDagaba.