AFRICAN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDIES

OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Volume 33

TECHNOLOGY, TRADITION AND

THE STATE IN AFRICA

TECHNOLOGY, TRADITION AND

THE STATE IN AFRICA

JACK GOODY

First published in 1971 by Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1971 International African Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-8153-8713-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48813-9 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-58512-6 (Volume 33) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-50539-3 (Volume 33) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

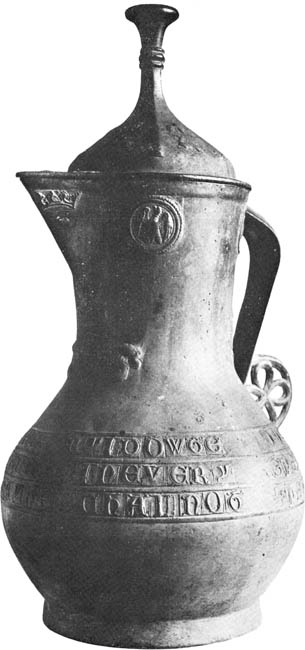

Jug, now in the British Museum, bearing the arms of England and the badge of Richard II; discovered at a war shrine in Kumasi when the British defeated the Ashanti in 1896.

TECHNOLOGY, TRADITION, AND THE STATE IN AFRICA

JACK GOODY

Published for the

INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN INSTITUTE

by

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON IBADAN ACCRA

1971

To

Esther

CONTENTS

Oxford University Press, Ely House, London W. 1

GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON CAPE TOWN SALISBURY IBADAN NAIROBI DAR ES SALAAM LUSAKA ADDIS ABABA BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI LAHORE DACCA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE HONG KONG TOKYO

SBN 19 724184 0

International African Institute 1971

Printed in Great Britain by

The Eastern Press Limited, London and Reading

I T is the thesis of the present work that the nature of indigenous African social structure, especially in its political aspects, has been partly misunderstood because of a failure to appreciate certain basic technological differences between Africa and Eurasia. It is these differences that make the application of the European concept of feudalism inappropriate. But the problem is not only historical; in many areas traditional African social structure exists (in a somewhat modified form) precisely because the rural economy has not greatly changed. It is not only the comparative analysis of historians and sociologists that needs to take cognizance of these facts, but also the decisions of planners, developers, and politicians (both reforming and conserving).

In writing this monograph I have received help and advice from many colleagues: John Fage, Daryll Forde, Max Gluckman, Thomas Hodgkin, George Homans, Edward Miller, M. Postan; all have helped me to avoid some of the errors that an individual must make when he steps outside the narrow compass of his professional discipline. John Fage asked me to discuss the subject of the first chapter at a seminar in London in May 1962; it was subsequently published as Feudalism in Africa? in the Journal of African History, iv (1963). Thomas Hodgkin invited me to read further papers on the military side at his seminar in Oxford. The second chapter was first presented to Professor Postans seminar in economic history in Cambridge. Subsequently I rewrote it to give as the St. Johns College Lecture at the University of East Anglia in 1968 and published it in The Economic History Review, xxii (1969). My thanks are due to the editors for permission to reprint these two papers in a revised form.

The drawings of the harness belonging to the Chief of Kpembe were made by Anna Craven when she was working as a research assistant with my wife, Esther Goody. I am also grateful to my wife for her help with the index and proofs.

St. Johns College Jack Goody

Cambridge

November 1969

W AS feudalism a purely Western phenomenon? Is it a universal stage in mans history, emphasizing replacement of kinship by ties of personal dependence which further social development required? If it is neither a universal prerequisite nor yet exclusively Western, what are the conditions under which it is found? A host of such questions are raised by the continual use, both by historians and sociologists, of the term feudal as a description of the societies they are studying. Here I want to inquire into the implications and value of the concept as applied to African social organization.

First used, apparently, in the sixteenth century,; Marcel Granet entitled his study La Fodalit chinoise (1952); Pirenne and Kees discuss the question in dealing with Egypt; Kovalevski and Baden-Powell do the same with regard to India and Vasiliev for Byzantium.

Historians are not the only persons to use this term in a comparative context. Social anthropologists have employed it in an equally all-embracing way. Roscoe and others have seen the Baganda as feudal Rattray the Ashanti, Nadel the Nupe of northern Nigeria. Indeed it would be difficult to think of any state system, apart from those of Greece and Rome, upon which someone has not at some time pinned the label feudal. And even these archaic societies have not been left entirely alone. Feudal relationships have been found in the Mycenean Greece revealed by the archaeologists and epigraphers, while it is generally agreed that one element in medieval feudalism was the institution of precarium of the later Roman Empire.

Unless we assume the term has a purely chronological referent, then, or unless we are to take our smug refuge in the thought that persons, events, and institutions defy comparison because of their uniqueness, the use of any general concept like feudal, more particularly concepts like fief or client, must have comparative implications. Marc Bloch realized this when at the end of his classic study he wrote, Yet just as the matrilineal or agnatic clan or even certain types of economic enterprise are found in much the same forms in very different societies, it is by no means impossible that societies different from our own should have passed through a phase closely resembling that which has just been defined. If so, it is legitimate to call them feudal during that phase. (Bloch, 1961: 446.)