Introduction

Andrea Capra

Lucia Floridi

Notes: Some of the essays included in this volume were originally delivered as papers at the conference Intervisuality and Literature in Greece and Rome (Milan University, February 78, 2017). Many thanks to the speakers as well as to those who joined the project at a later stage. Thanks are also due to the University of Milan for funding the conference back in 2017 and to Durham University for covering the additional expenses associated with the editorial process (pictures and proofreading). Finally, our warm thanks go to the anonymous readers for their encouragement and useful feedback.

Intertextuality is a well-known tool in literary criticism and has been widely applied to ancient literature, with classical scholarship being unusually at the frontline in developing new theoretical approaches.

Through contributions from a diverse team of scholars, this book aims to bring intervisuality into sharper focus and show its potential as a tool to explore the research field traditionally referred to as Greek literature.

Why intervisuality is relevant to Greek literature

If one were to mention two distinctive phenomena that define Greek civilisation, the choice would easily fall on the symposium and on theatre. While originally imported from the east, in the archaic age the symposium rapidly turned into a hallmark of Greekness, perceived as such by contemporary civilisations. The symposium is a quintessentially synaesthetic phenomenon, involving all senses and providing a natural setting for most archaic poetry. As is well known, the interaction between poetry and images, especially as depicted on pottery, is integral to the symposium and to most of what we moderns refer to as lyric poetry, delivered as song accompanied by music. Accordingly, such poetry is intrinsically intervisual and connected with the specific occasions in which the songs were performed. Archaic poetry could also be performed outdoors, in which case it often referred to and was informed by the topography of the relevant settings, such as monuments and performance spaces, thus providing further opportunity for intervisual interplay. This book explores both strands, which ultimately rest on what many scholars, in the wake of Bruno Gentilis seminal work, refer to as the pragmatic nature of archaic Greek poetry. Both strands were of course influenced by the exceptionally vivid quality of Homeric poetry, which is why a chapter on Homer precedes our discussion of lyric poetry.

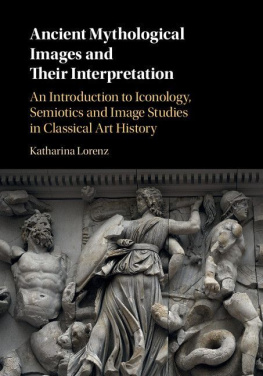

A quintessential example of Homeric vividness, the heroic duels found in the Iliad intriguingly resonate with images known from Bronze Age seals while at the same time activating an equally vivid form of flashbulb memory in the minds of the audience, as argued in George Gazis chapter. Whereas the relationship between the images painted on sympotic vases and the poetry sung at symposia is the specific focus of Riccardo Palmiscianos essay, Cecilia Nobili investigates the intervisual allusions to Athenian public spaces in the works of lyric poets. Carmine Catenacci instead examines how the visual experience of the first individual portraits, which filled public spaces in the Ionian and Athenian area between the sixth and the fifth century BCE, affected the word of the poets (and vice versa).

As one would expect, this book also includes Attic theatre and its subsequent ramifications. Even more than the symposium, theatre implies a spectatorship no less than an audience; at the same time, with the spread of literacy, both sympotic and theatrical poetry end up acquiring a readership and inform later forms of One of the most influential legacies of Greek literature, theatre somehow superseded the symposium as it rapidly turned from a one-city institution into a hallmark of Graeco-Roman civilisation. In the process, theatre, a visual no less than a verbal art form, triggered a series of related images in all sorts of media throughout the ancient world, and this extraordinary dissemination has been gaining traction in scholarship over the last few decades. Well beyond the narrow boundaries of text-focused approaches, new interpretative paradigms are trying to pin down such complex and heterogeneous material. This shift, as well as the pragmatic nature of Greek poetry, cannot but affect our understanding of intertextuality, which can hardly be grasped in full without its (inter)visual counterpart.

As noted by Antonis Petrides, ancient theatre is a form of performance in which allusion was not necessarily achieved by virtue of verbal markers, but also by the ability of the visual element, too, to make references to various semiotic systems collaborating in the creation of theatrical meaning. Intertextuality, in the case of Menander, encompassed intervisuality as well. However, this volume shows we hope that the relevance of intervisuality for Greek theatre is not limited to Menander, nor solely to be understood in the relatively narrow meaning adopted by Petrides. The intervisual entanglements of theatrical performance are at the core of both Anton Bierls and Lucia Athanassakis chapters: while Bierl focuses on the complex and multifaceted visual aspects of the text of Aeschylus Oresteia and on their dramatic application, Athanassaki explores the political significance of Euripides dialogue in Erechtheus with three important Athenian temples the West Pediment of the Parthenon, the temple of Athena Nike, and the Erechtheion.

Intervisuality is relevant to Greek literature both before and after the golden age of Attic theatre (fifthfourth century BCE). Not only is theatre less an invention ex nihilo than the development of (highly spectacular) epic and lyric performances addressing both local and pan-Hellenic audiences; even more importantly, what we call Greek literature, a word that has no equivalent in classical Greek, is by and large a form of verbal art inextricably linked with performative contexts, whether imaginary or real. These contexts, in turn, work as a repository of mental images shared by both authors and audiences. As a consequence, the importance of visual components is integral to the very process of producing and consuming Greek literature.

This close and complex interaction between words and images persisted even when the pragmatic nature of Greek literature gradually declined and gave way to a more bookish production. After the classical age, virtually all genres continued to refer to the quintessentially visual poetry of Homer a point that is of course integral to George Gazis essay as well as to the intervisual poems and plays connected with the symposium and with theatre. At the same time, the ubiquitous dissemination of ekphrasis meant that such references to the (inter)visual past of Greek poetry were in constant dialogue with a vast repository of contemporary images. This is why intervisuality remains a powerful tool to make sense of such a complex phenomenon well into the Hellenistic age. In this volume, Benjamin Acosta-Hughes provides an intervisual reading of the surviving poetic passages on Arsinoe-Aphrodite in conjunction with images of Arsinoe.

If anything, the relevance of intervisuality becomes even stronger in the imperial age when, as already mentioned, verbal and figurative codes come to be conceived of as strictly parallel forms of expression. Such a pervasive complementarity takes different forms, which this book explores in depth, if selectively. Ewen Bowie focuses on modes of intervisuality in display speeches, in sung poetry performances, and in the singing of ceremonial hymns in Greek cities of the second century CE, suggesting that the impact of all such performances on the audience was modulated by visual features of the performance environments. Lucia Floridis and velyne Priouxs chapters, respectively devoted to Lucians