The Parliaments of Early Modern Europe

First published 2001 by Pearson Education Limited

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2001, Taylor & Francis.

The right of Michael A.R. Graves to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or here-after invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN 13: 978-0-582-30587-8 (pbk)

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book can be obtained from the Library of Congress

Typeset by 7 in 11.5/13pt Van Dijck

_____________________________________________________

Contents

_____________________________________________________

| APH | Acta Poloniae Historica |

| AHR | American Historical Review |

| BIHR | Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research |

| HJ | Historical Journal |

| PER | Parliaments, Estates and Representation |

| P&P | Past and Present |

| SHR | Scottish Historical Review |

| TRHS | Transactions of the Royal Historical Society |

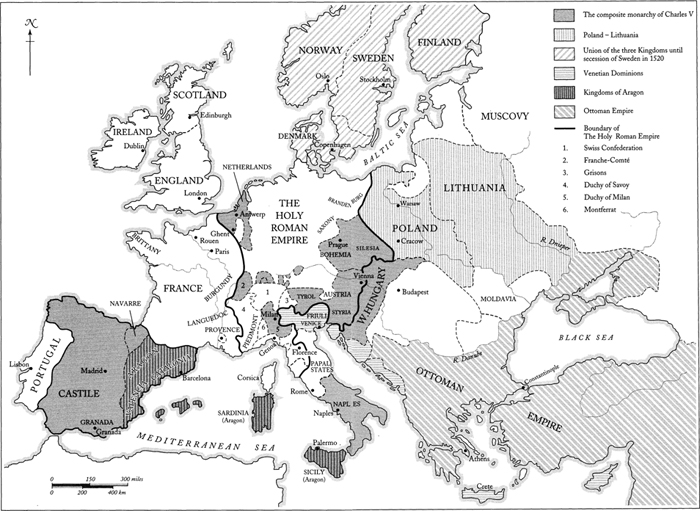

_____________________________________________________

T HE PURPOSE of this volume is to examine the fortunes of representative assemblies during a critical period in their history. The institution of parliament is central to modern political history, and not only in Europe which is the particular concern of this study. It was also very important in most parts of early modern catholic Christian Europe. As meetings between the ruler and his socio-political elite, representative assemblies were not only political fora, in which he sought advice and his subjects aired grievances, but also occasions on which auxilium (aid), especially in the form of taxes, was given to him and laws were enacted on a wide range of political, religious, social and economic concerns. As we proceed, however, such a statement will need qualification. Perhaps the only two constants in early modern European parliamentary history are variety in kind and variability over time. Assemblies, variously identified as parliaments, diets or estates, had titles which differed from one country, region or locality to another. They also differed widely in the time, rate and nature of their development, their structure and composition, functions and authority, and their relations with the ruler.

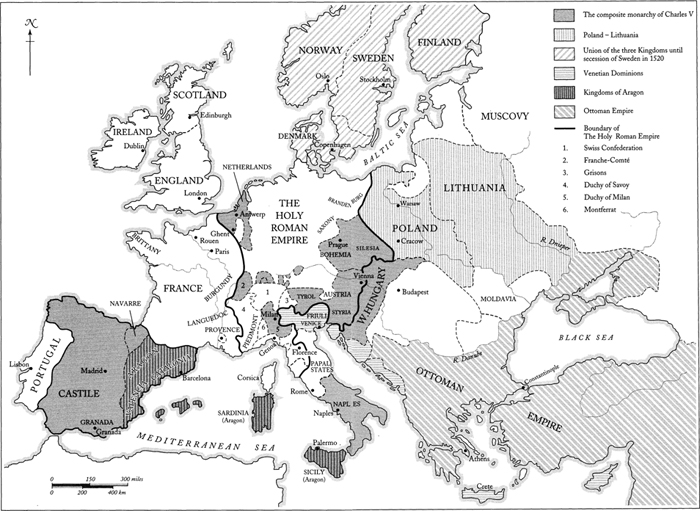

Any study of European parliaments must encompass and, where possible, explain such diversity. It also needs to put to rest common misconceptions about their historical development. The parliamentary tradition on the European continent is very old and not a relatively recent phenomenon triggered by political idealism and the French Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it should be emphasised that, in age at least, the English representative assembly was not the mother-of-parliaments. When it came into existence as an identifiable parliament, it was younger than the assembly of Leon and just one of a number of institutions emerging in the thirteenth century in parts of the Spanish peninsula, Sicily, Germany and elsewhere. Furthermore, at least until the seventeenth century, some continental content and giving voice to grievances. They gave public expression to problems and alerted the government as to what was going on, or going wrong, out there in the various parts of the kingdom. In other words, a parliament was a mirror which reflected the current issues, problems and stresses in the wider community. Charles I of England became painfully aware of this when he met his last assembly, the Long Parliament, in 1640. Of course, an examination of that English crisis or indeed of any crown-parliament confrontation in isolation does not provide a European dimension. That dimension is provided partly by the comparative framework of this study, but also by the due consideration of external forces, which often impacted on relations between ruler and subjects, king and parliaments. The politics, diplomacy and military burdens of the Thirty Years War (161848), for example, had an important, even crucial, effect on the fortunes of assemblies in those countries caught up in the conflict. Developments in national, regional and even local representative institutions often become meaningful only if they are examined within the broader contemporary European context.

Although this is not intended to be a narrow, technical, institutional study, due attention will be given to institutional characteristics such as organisation, structure, functions and membership. Such characteristics were vital to the historical role of representative assemblies: to their relative efficiency and productivity; to their ability to support the ruler with aid and counsel and, at the same time, to represent both specific interests and those of the wider community; and above all to their capacity to protect such interests, even to survive, in the hostile political climate of early modern Europe. The last of these is the central concern of this study. The early modern period was an age of revitalised, aspiring, strong and in some cases even autocratic kingship and eventually, in some countries, of absolute monarchy. As ambitious rulers jettisoned medieval ideals of moral obligation, consensus and power-sharing in pursuit of more effective and authoritarian government, they targeted obstacles to the fulfilment of their long-term policies. Prominent amongst the obstacles were representative assemblies, in which those medieval ideals were entrenched and which often included the social orders and corporate groups most threatened by expansive monarchy. Some princes sought to subordinate them, manipulate them, or simply leave them in abeyance. In response, European assemblies became, in varying degrees, the watchdogs of privilege and power-assemblies, such as the Cortes of Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia, the Sicilian