At

Home

with

Nature

A Guide to Sustainable,

Natural Landscaping

JOHN GIDDING

To my mom, Irene Kaino, for her love of art.

To my dad, John Gidding, for his love of history.

Contents

Cedar, and Pine, and branching palm, a Sylvan scene! And as the ranks ascend shade above shade, a woody theatre of stateliest view. Paradise Lost (1667), John Milton

I grew up astride the Bosporus and received a secondary education on an Alp. Perhaps my interest in nature was briefly awakened then, trading back and forth exotic sea passages for mountains. Nor would this interest have been inconsistent with my burgeoning love for architecture and my city, but Istanbul is treeless and I first learned to love neighborhoods for their concrete and stone, their history and heritage, and their architectural diversity. By the time I showed up at Yale and Harvard, I knew I would study architecture.

Natures inspiration first came in the form of my first job after graduate school, at a landscape architecture firm in New York City. Michael Van Valkenburgh had been at the forefront of ecological urbanism since 1982 and was busy presenting award-winning visions for the Brooklyn Bridge Park and Union Square when he gave me my first practical experience applying ecology to landscape design. I was on the team tasked with developing a design for the rooftop of the Washington, DC, headquarters of the American Society of Landscape Architects. The design called for two 10-foot-tall waves of vegetation, facing one anothera horizon rediscovered, cradling views of the city. The plant selection was purposefully broad as part of a long-term study of their felicity, one of the extended educational goals of the project, and were studied, photographed, and even kept on a webcam stream. The plants native to the mid-Atlantic region thrived compared with some of the foreign fronds, which required irrigation. An invaluable early lesson.

My second wakeup call came in a bamboo field in Zhejiang province. I was in China in 2007, choosing a diverse array of bamboo species for a pavilion at the upcoming Beijing Olympics. The pavilion was to be encircled with cascading bamboo gardens, some as tall as 60 feet high. China, also known as the Bamboo Kingdom, has over half of the worlds native bamboo species, some 500 in all. Over three intensive excursions, I came in contact with many regional horticulturists as they led me through forests of bamboo, explaining how these forests have been sustained and harvested for generations, their health maintained. Given that the Chinese have been cultivating bamboo for well over 3,000 years, their horticulturists are often called upon to distinguish between bamboo native to a region and those native to other regions, the former being essential for the health of the forest, the latter less so. Because the cultivation of some bamboo species was so ancient, a horticulturists knowledge of a regions biological and human history seemed essential to a full understanding of the imperatives of the regional ecology. Another invaluable lesson. I visited a number of Chinas famous gardens and parks and have admired their landscaping techniques ever since.

Whatever may have been the fruits of my extensive education and brief apprenticeships in the world of architecture and urban design were quickly ripened when I decided to portray a fully fledged landscape architect on reality television. It was my circumstance to portray mastery of a profession I hadnt mastered, but the limited scope of work for TV design was such that I could do my research. My first few seasons of TV were spent redesigning front yards, restoring facades, and bringing some color into suburban neighborhoods. My focus was skewed toward the architecture. The landscapes were mostly new lawns, the kind that comes in rolls and makes all the mud disappear the last day of shooting. Not only was it great for TV production, but lawns were also what the homeowners, the networks, and the advertisers were requesting, and they came with accessories like irrigation systems, lawnmowers and glyphosate to kill weeds.

Id like to say the muse of environmentalism had begun to sing so urgently that rather than changing out dead lawns for new rolls of sod week after week, I finally started to adopt landscaping techniques that respected the environment. It wasnt the case. My excuse is that I hadnt yet seen an alternative that could replace the suburban ideal. Instead, I would speak with local nurseries about which plants would thrive at our project site and insert a few native hedgerows here and there.

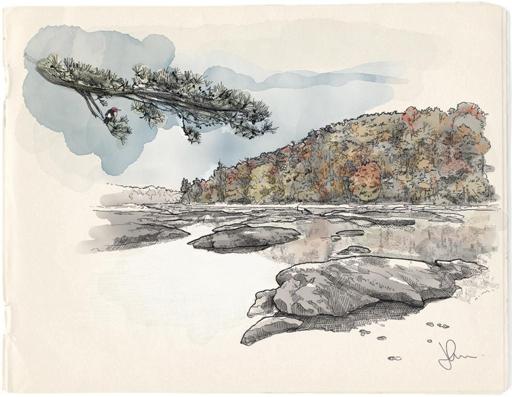

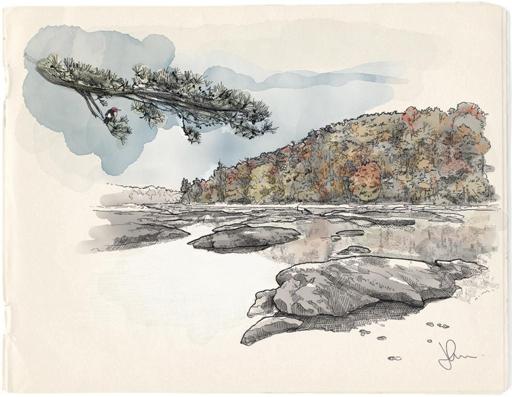

During filming in Atlanta, I would sometimes find myself close enough to the Chattahoochee forest, where a river winds through the citys suburbs, to take a walk along the riverbank, sketchbook in hand. By a fluke of urban amnesia, this part of the Chattahoochee had been spared Atlantas rapid development. With the forest intact, the river ran cool and clear. It was as John Milton described, a Sylvan scene. My sketches of the clusters of trees leading down to the river, the curving lines of riparian shrubs and grasses around them, and their natural clearings, became the vision of a native landscape that started to coalesce in my mind as one that could reunite suburban yards with the natural world by sheer dint of its sylvan charms.

The TV work brought me into the homes and gardens of neighborhoods across the nation, and I developed a deep fondness for suburbia. It was initially foreign, with a litany of rules and regulations set by HOAs and neighborhood committees, but with architectural vitality, enormous acreage, and spending power. I was also traveling throughout the states as a guest speaker at Home & Garden shows, treating each Q&A session like a laboratory of home-owning concerns in my quest to come up with new presentations. I came away convinced of the revelation I knew would not be welcome among those steeped in the tradition of lawn maintenance; to restore the degraded habitat upon which the suburbs had been erected, their inhabitants had to start hearing the growing chorus for native plants. Like Darwin, I have hesitated long before making my views public.

Native plants, having evolved over untold millennia, have established a self-regulating ecosystem that protects them from disease, and they require no more water than is provided by the regions normal precipitation. At Home with Nature is a step-by-step guide by which suburban homeowners can design, with native plants, sustainable, beautiful landscapes for their own property. A key element of this sylvan style of landscaping will be the use of a greater number of trees than are usually found in a suburban yard, leading to a landscape that is aesthetically pleasing, in harmony with and supportive of the local environment.

The future health of our own habitats, and that of many species of wildlife, depends upon our capacity to adopt responsible strategies of landscape design, allowing a mix of spaces for people and wildlife, without taxing limited resources. Hearing the alarms of impending climate disasters nationwide, American suburbs are becoming newly receptive to bold design ideas, and at a time when they are in a unique position to meet the challenge. The time is now.

Only 1.5% of Istanbul is public green space (parks and gardens), the lowest of 44 cities in the World Cities Culture Report , 201314. New York has 14%, Paris 9.4%. Moscow leads with 54%.

Next page