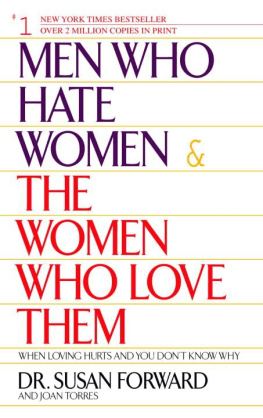

UNDER MY THUMB

UNDER MY THUMB

SONGS THAT HATE WOMEN

AND

THE WOMEN WHO LOVE THEM

Edited by Rhian E. Jones and Eli Davies

Contents

Introduction

Rhian E. Jones and Eli Davies

While women have always been offered songs that love, defend and celebrate them, there is an equally long tradition of music that does the opposite. In lyrics, videos, album artwork and the music industrys everyday operations, women see themselves attacked, excluded, stereotyped, fetishised and viewed purely through their impact on the male ego. But this hasnt stopped generations of women from loving, being moved by and critically appreciating this kind of music no matter how that music may feel about them.

Being a woman and a music fan can feel like hard work at times. Back in 1970, a writer named Arlene Brown expressed her disappointment with the contemporary rock scene in a piece entitled Has anyone reading this article met a woman bass player. At one point, she recounts her experience at a Grateful Dead concert:

Something inside me went boom. There I was digging this beautiful voice, beautiful guitar, but with words about some womans box [] I felt pretty sullen

Here, Brown describes the contradictions that can still confront women invested in music today. The visceral thrills, exhilaration and anti-establishment kicks theyre there for us as well as the boys, but so often theres an undercurrent to our appreciation that whispers: this music doesnt like me or this music doesnt even acknowledge that I exist. When stories are told about bands, artists and gigs, women are either completely written out of them or featured only in relation to men as delicate muses, insatiable groupies or a swarm of faceless fangirls meaning that our own experiences, ideas and arguments about the music we love are marginalised or glossed over. Traditionally, the boys not only do music, they also criticise, analyse and canonise music. The girls? Were just there to applaud and appreciate.

Mens experiences and mens experiences of women have structured so much of the music we listen to. If this is ever noticed by male fans and listeners, many will see it as just the way it is, barely worthy of comment or deserving of challenge. Among other things, this highlights how the ability to consume problematic media often relates to your real-life proximity to it. Men do not face the same threat of sexual violence, harassment and objectification that women do, and so will necessarily have a different reaction to hearing music which is predicated on the subordination, exploitation or exclusion of women. But being a female music fan affects your physical experience when out in the world at gigs, at clubs, on the dancefloor, in conversations, at the bar, on your journey home and can change the ways you feel able to relate to an artist, band, scene or subculture.

Over forty years after Arlene Brown wrote her article, Jessica Hopper published The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic. Although, as she acknowledges, the accuracy of the books title is up for debate, its intention was to highlight a broader lack of awareness and acknowledgement of women as music fans, listeners, critics and writers. In the essay Emo: Where the Girls Arent, Hopper observed that sections of the alternative music scene were no more immune than the mainstream to regurgitating reactionary values of male chauvinism. Her objections to this fit into a long tradition of how women relate to the music they love:

[T]he well-worn narrative of the boy rebels broken heart, as exemplified by the last 50-plus years of blues-based music [] men writing songs about women is practically the definition of rock n roll. And as a woman, as a music critic, as someone who lives and dies for music, there is a rift within, a struggle of how much deference you can afford, and how much you are willing to ignore what happens in these songs simply because you like the music.

The sexism and misogyny which often attaches to music also influences mainstream music journalism, both in its relative lack of writing by women and in the attitudes of male writers to performers and fans. Classically, a musicians credibility is judged by the nature of their fanbase, with a following of screaming teenage girls or frustrated housewives cited as reasons not to take a band or artist seriously. The same attitudes are present in the wider culture surrounding music: in documentaries, articles, panel discussions, interviews and autobiographies. Some of these areas have seen signs of improvement, particularly since the rise of women writing about music themselves whether memoirs by musicians like Pauline Black, Viv Albertine and Kim Gordon, or works of criticism and celebration by writers like Ellen Willis, Laina Dawes, Sylvia Patterson and Lavinia Greenlaw. But despite this evolution in music writing, and the increase in alternative media sources providing space for women to write on popular culture, there is still a lot of ground to cover in reflecting the range of identities and experiences women can have. Articles like that by former musician Emma Jackson, on retrospective sexism when looking back on Nineties music, describe a music industry and cultural history still submerged in sexist assumptions that enable the unthinking erasure of womens contributions and perspectives.

Partly inspired by Jacksons piece, Eli wrote about her own experience as a music fan in the Nineties, from a viewpoint she felt had been resolutely ignored by the critical consensus. The response to this article on social media and elsewhere, from other women who felt similarly, is part of what pushed us to put this book together. We wanted to collect these stories and experiences not only in order to assert some balance, but also to explore specifically the messy, complex and confusing and at the same time thrilling, fulfilling and life-changing relationships that women can have with music and musicians.

***

There is, of course, no single definitive female identity or one way to experience music, which is something we were keen for this collection to emphasise. This books contributors cover a variety of music, subjects, styles and opinions. The essays are grouped loosely by chronological order and their references to songs and bands beyond their central subject mean that many of them have points of incidental but illuminating crossover with each other. The books connecting thread is that all the beloved bands, artists and songs discussed here might be found off-putting, politically troubling, ridiculous or even dangerous from other perspectives. In recognising the dubious aspects of the music and musicians they love, writers variously critique them, denounce them, laugh about them, or find ways to positively channel them, fashioning subversive or empowering lessons from often unpromising material. Throughout this process, gender interacts with class, race, sexuality and other aspects of an individuals identity.

While there has been no shortage of women capable of expressing themselves through music, it has taken decades for them to achieve mainstream visibility and to be taken seriously on their own terms. However, as many of these essays show, women have always been able to sing along with the male voices made available to us, even though we know we arent singing from exactly the same hymn-sheet. Needing an outlet for a deeply-felt but unarticulated anger, disaffection or rejection of the status quo and the social roles imposed on us, many women found affinity and solidarity with the resistance and resentment expressed by male artists, even while recognising its limits and flaws. Writers who identify with or admire a whole array of male misfits, male rebels and angry young men from Tupac to Jarvis, Elvis Costello to Eminem, Kanye to Rivers Cuomo can also regret that women seldom see themselves represented in the same terms or allowed the same indulgences.

Next page