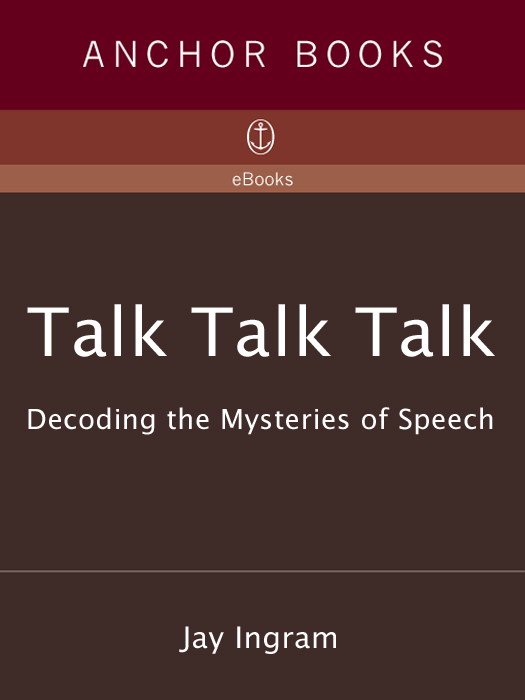

A N A NCHOR B OOK

PUBLISHED BY DOUBLEDAY

a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10036

A NCHOR B OOKS , D OUBLEDAY , and the portrayal of an anchor are trademarks of

Doubleday, a division of Bantam Doubleday

Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

Talk, Talk, Talk was originally published in Canada in 1992 in Viking by

Penguin Books Canada Limited.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ingram, Jay.

Talk, talk, talk : decoding the mysteries of speech / Jay Ingram.

1st Anchor Books edition,

p. cm.

1. Speech. 2. Oral communication. I. Title.

P95.I48 1994

302.2242dc20 94-9134

eISBN: 978-0-307-78811-5

Copyright Jay Ingram, 1992

All Rights Reserved

v3.1

To Rachel and Amelia for teaching me

how children learn language, and to

Cynthia for teaching me about

interrupting.

Acknowledgments

I dont even remember what hooked me on language in the first place, but I do know that without the kind of help provided by the people named below, this book would never have got off the ground.

Dr Ian Mackay, a linguist at the University of Ottawa, set me straight on some of the mechanics of Foster Hewitts He shoots, he scores, and his colleague Konrad Koerner made clear some of the mysteries of Proto-Indo-European. Neil Smith at the University of London was kind enough to send me some of the research hed done on Christopher, a linguistic savant. Dr William Samarin made available some of his audio tapes of tongue-speakers, and Dr Myrna Gopnik at McGill took a great deal of time to make sure I had all the information I needed about genes for language. Helen Neville and Julian Jaynes sent me material about their research and answered my questions, as did Geoffrey Beattie at Sheffield University and Susan Curtiss at UCLA. I am indebted to Aura Kagan at the Aphasia Centre in North York for letting me talk to several people there who put a human face on the condition of aphasia.

Evelyn Chau was in the right place at the right time as far as I was concerned: she did some of the early research that convinced me this book was possible. Writers may sometimes get the feeling that the publisher views their creative output in roughly the same way as a grocer does a shipment of fresh tomatoes (I was once told that my previous book had had the best cover of the fall season), but the people at Penguin Canada, especially Cynthia Good, Karen Cossar and my editor, Meg Masters, have succeeded in making me feel at home. And I finally figured out how to sneak page after page past copy editor Mary Adachi without having her obliterate them with notes and questions: just let her cats walk all over the manuscript as youre discussing it.

And of course my family, who are on the front lines of all this, put up with months of my closeting myself on the third floor of our house to finish the book, and I can only promise them that Ill spend more time at home now.

Contents

Introduction

This book has come at a perfect time for me, because Ive been able to write while listening to my two daughters as they learn to talk. Theyre typical of most children their age: they dont try very hard, the mistakes they make dont trouble them (if they even notice them) and they are oblivious to the great leaps forward they are making. That is the most striking thing: children learn to express themselves without even realizing that it should be difficult to do. Rachel, when she was five, started to begin the occasional sentence with Actually Actually?! I know Id never taught her the meaning of that wordIm not sure I could. And yet the first time she used it, she had it in exactly the right context, even with the reflective pause, head tilted, that should sometimes accompany that word.

Child psychologists have pointed out again and again that children learn both an amazing vocabulary (at a rate of something like ten new words every day) and a set of extremely complicated rules for putting those words into sentences, without anyone explaining how they should do it. Children arent even told that there are rules; they just somehow figure them outalthough how is still a puzzle.

Its not just children. We all perform amazing linguistic feats in everyday conversation, and most of the time wed be completely unable to explain how we knew what to do. The other night I heard this on the radio broadcast of a Toronto Blue Jays game: Winfield might be even more careful in this at-bat if he were to take the Baltimore-Milwaukee score on the Zurich Insurance Canada out-of-town scoreboard into account. Wow! Winfield would end up leaving his bat on his shoulder if he tried to analyze that sentence! But of course we never waste time analyzing sentences, we just produce them, instantly and without effort, no matter how many clauses, phrases and indirect references they contain.

In fact, complete grammatical sentences are a bit like unspoiled nature: much rarer in reality than in our imaginations. If you could see an exact sound-for-sound transcript of a real conversation, you would be shocked at how incomplete, sloppy and unfinished it is. Half-sentences, parts of words, interruptions: its almost incomprehensible, at least to the eye. But to the ear? Thats different, because even though those words are coming at you faster than theory says you should be able to handle them, you hear them, understand them and can make up an answer instantaneously.

These are just some of the features of language that are still not well understood, and the attraction of all of them is that they are accessible. Theyre not locked away in the nuclei of atoms, or lost somewhere in remote galaxies. The phenomena that language researchers study are things you canand doexperience every day, for example, the signals that pass back and forth between partners in conversation to ensure that each gets a turn, or the familiar hesitation of getting caught with a word on the tip of the tongue. You only need to take a minute to look (actually, to listen), and the mysteries of language will make themselves plain to you.

It isnt always fun and games. At the Aphasia Centre in North York, just north of Toronto, adults who have known what its like to be able to express themselves freely and fluently, sometimes in several languages, are now trying to learn to talk again, and for them the task has none of the delights of childhood. Their language skills have been crippled by strokes, and even those who have taken great strides back towards normal conversation are perfectly aware of how far short they still fall. Talking to them is a startling revelation of how much goes into a typical casual conversation. These people are cut off from a world the rest of us talk our way through with ease.

Its that ease of language that allows us to forget how complex talking is, but if you take a moment to pay attention, you cant help but marvel at it. Wherever possible in this book, Ive tried to show how everyday conversation is full of opportunities for seeing through the superficially simple into the deep, and surprising, world of talk.