Roots of the Issei

Exploring Early Japanese American Newspapers

Roots of the Issei

Exploring Early Japanese American Newspapers

Andrew Way Leong

Foreword by

Eiichiro Azuma

An essay published under the auspices of the

Japanese Diaspora Initiative,

Hoover Institution Library & Archives

Kaoru Ueda, curator

HOOVER INSTITUTION PRESS

Stanford University

Stanford, California

| With its eminent scholars and world-renowned library and archives, the Hoover Institution seeks to improve the human condition by advancing ideas that promote economic opportunity and prosperity, while securing and safeguarding peace for America and all mankind. The views expressed in its publications are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Overseers of the Hoover Institution. |

www.hoover.org

Hoover Institution Press Publication No. 694

Hoover Institution at Leland Stanford Junior University, Stanford, California 94305-6003

Copyright 2018 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher and copyright holders. For permission to reuse material from Roots of the Issei: Exploring Early Japanese American Newspapers, by Andrew Way Leong, ISBN 978-0-8179-2205-4, please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of uses.

Efforts have been made to locate original sources, determine the current rights holders, and, if needed, obtain reproduction permissions. On verification of any such claims to rights in the articles reproduced in this book, any required corrections or clarifications will be made in subsequent printings/editions.

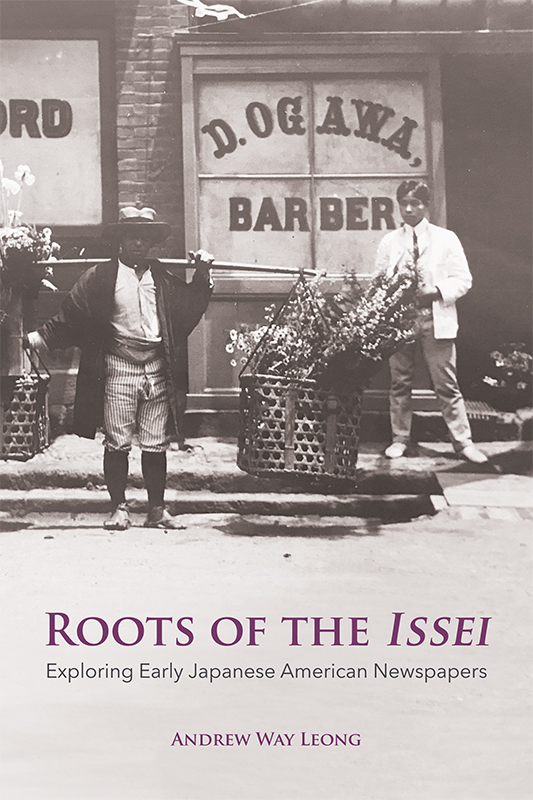

About the cover photograph: Flower vendor on street in front of D. Ogawa Barber at No. 103 Honmachi Road, Yokohama, on June 3, 1906. The Yokohama port was a starting point of the journey for many Japanese in the United States. Source: Paul N. Woolf photograph collection, Envelope A, Hoover Institution Archives.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8179-2205-4 (paperback)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8179-2206-1 (EPUB)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8179-2207-8 (Mobipocket)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8179-2208-5 (PDF)

FOREWORD

The Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection: Possibilities and Limitations

Eiichiro Azuma

From the vantage point of researchers who are interested in the lived experiences and raw perspectives of Japanese immigrants (Issei) and their second-generation (Nisei) children in North America and beyond, the Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection is a godsend. Since the emergence of Asian American studies in the early 1970s, researchers have struggled to salvage the voices of Issei and the traces of their activities beyond what has been recorded and told by white intellectuals and punditsexclusionist and anti-exclusionist alikein English-language source materials. The language gap and academic orientalism, as well as the lack of central repositories for vernacular immigrant primary sources, rendered the historical narratives of Japanese Americans so lopsided and one-dimensional that their experiences remained a buried past well into the mid-1970s.

Pioneer Japanese American historian Yuji Ichioka was among the first scholars to advocate the importance of vernacular ethnic newspapers (hoji shinbun) as a vital source of information to properly understand the ideas and practices of Issei as historical agentsnot simply as the objects of white American race/nation-making projects.

Since these methodological shifts, and with the use of transnational archiving, researchers in the United States and Japan have utilized immigrant-language ethnic newspapers preserved as microfilm at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and other archives and libraries. Ironically, old copies of many Issei newspapers were relatively available because various institutions of higher education and public libraries had kept them due largely to World War II, despite the neglect of such sources in academia. Since the late-1930s, US military intelligence and the FBI had made extensive use of hoji shinbun to obtain raw data on Isseis pro-Japan activities and their alleged disloyalty to the United States. The microfilmed papers included many hoji shinbun that the US government had used against Issei and Nisei in the context of its decision to incarcerate them based on the claim they posed a national security risk during the early 1940s. Three decades later, Asian American historians started to rely on the same sources to present alternative historical narratives. The advent of Asian American studies has enabled us to generate new theoretical and analytical frames to understand the complex experiences of Issei and Nisei in light of racism and other neglected issues. Without the hoji shinbun sources, it would have been impossible to have the kind of nuanced interpretations grounded in the actual analysis of Japanese Americans ideas and actions beyond orientalist presumptions that they were the vanguard of a yellow peril. Regrettably, substantive historical scholarship that draws on hoji shinbun sources is still rare, since it takes much time and trouble to read through the microfilmed newspapers that are written in an archaic and idiosyncratic form of Japanese.

The Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection (HSDC) makes these vital historical sources far more accessible and much easier to navigate. Not only does it allow researchers to go over the online material anywhere and anytime, but the digital database also offers various search functions to sift through a mountain of information. (Those functions are not perfect, so researchers still need to try different waysfor example, multiple key/subject words and different kanji spellingsto cast their nets as wide as possible.) Older generations of researchers like me, who used to toil weeks and months in dingy microfilm reading rooms, may feel envious. But this new collection will definitely lead to the production of better-informed and more sophisticated scholarship in the years to come. We owe it to the Hoover Institution (especially Kaoru Ueda, who oversees the HSDC) and an anonymous donor to make the best use of this wonderful database and retrieve the still buried past of Japanese Americans and other diasporic Japanese populations in the western hemisphere and beyond.

As a researcher who is familiar with hoji shinbun, I would like to close my preface with a few issues to keep in mind when availing oneself of this online material. First, the vernacular Issei newspapers entail all sorts of partialities and slants that stemmed from the uneven distribution of power and privilege within Japanese America (or any other Japanese community) in which they were put together and published. This is to say, the newspaper reports, editorials, and commentaries generally mirrored strong gender and class biases, since writers were mostly well-educated men. As much as