Issei Buddhism in the Americas

THE ASIAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE

Series Editor

Roger Daniels

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

Issei Buddhism in the Americas

Edited by

DUNCAN RYKEN WILLIAMS AND TOMOE MORIYA

University of Illinois Press

URBANA, CHICAGO, AND SPRINGFIELD

2010 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Issei Buddhism in the Americas / edited by

Duncan Ryken Williams and Tomoe Moriya.

p. cm. (The Asian American experience)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03533-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-07719-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. BuddhismAmerica. 2. JapaneseAmerica.

3. ImmigrantsAmerica. I. Williams, Duncan

Ryken, 1969II. Moriya, Tomoe, 1968

BQ724.187 2010

294.3928086912097dc22 2009048711

Contents

Foreword

ROGER DANIELS

Although the study of the The present volume is particularly welcome. Its authors focus on the varieties of the Japanese Buddhist immigrant religion experiences in Hawaii, the United States mainland, Canada, and Brazil. They treat both the formal religious structures and the largely religious language schools that became bones of political contention in Hawaii and North America. Until recently almost all English-language literature on Buddhism in America focused solely on the relatively few Caucasian converts while ignoring the much larger and expanding numbers of Asian American Buddhists.

Although it seems clear that the Buddhist newcomers were essentially just another variety of immigrant religion, they were not regarded as such by New World governments. From the 1920s on these governments, led by the United States, became increasing hostile to both Buddhist churches and language schools. The Japanese language schools in the United States found protection from onerous government restriction in a 1927 Supreme Court decision, Farrington v. Tokushige (273 US 284), but when war came in 1941 constitutional protections for Japanese Americans and Japanese American churches were simply disregarded. Buddhism was regarded as an enemy religion, and Buddhist priests and language teachers were well represented on the Department of Justices lists of persons to be interned at the onset of hostilities. After 1942, when the War Relocation Authority began the phased release of incarcerated Japanese Americans for resettlement in the interior, its regulations made it more difficult for Buddhists to regain their liberty.

The editors point out that, viewed from a Japanese perspective, the trans-Pacific expansion of Buddhism into the New World was a continuation of its eastward transmission from India through Southeast and East Asia to Japan. The offshoots planted in the New World received direction and financing from various church headquarters just as Christian churches that were part of the westward plantation from Europe looked to ecclesiastical authorities in London, Amsterdam, and Rome for direction and support.

Since many, perhaps most, readers will be unfamiliar with even the basics of Japanese Buddhism, the editors have provided a double set of introductions: the initial one at the beginning of the volume, and four mini-introductions, one at the beginning of each of the four parts into which the essays are divided. It might be prudent for some readers to read them all before beginning the essays themselves.

Note

. An earlier volume in this series, David K. Yoo and Ruth H. Chung, eds., Religion and Spirituality in Korean America (2008), focused on variants of Korean American Protestantism, Catholicism, and Buddhism.

Introduction

Dislocations and Relocations of Issei Buddhists in the Americas

DUNCAN RYKEN WILLIAMS AND TOMOE MORIYA

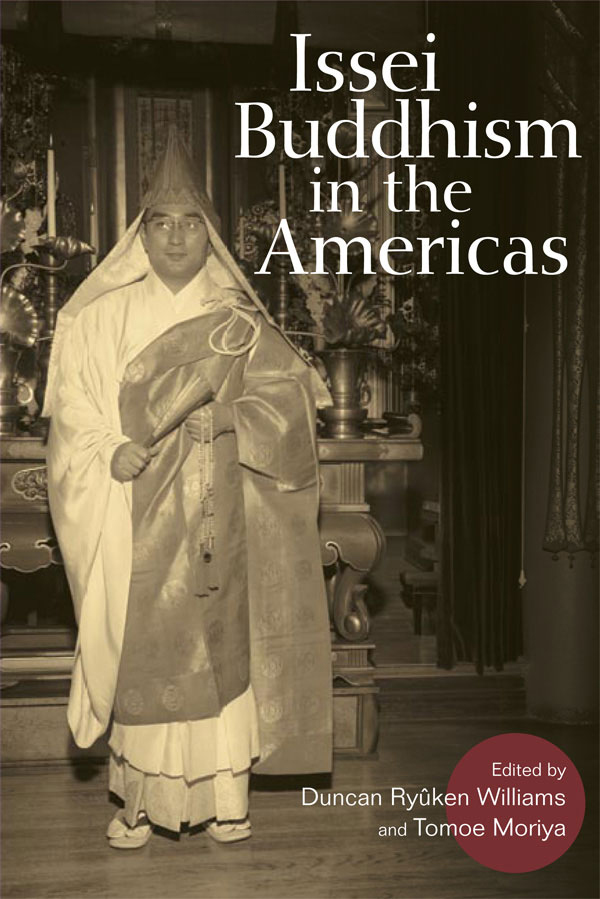

[Nishi] Hongwanji was

Ky Uchida, Bishop of the Buddhist Mission of North America (19051923)

Bukky t

t zen:

zen: The Eastward Transmission of Buddhism

Buddhists in Japan had long employed the idea of Bukky tzen, literally the eastward transmission of Buddhism, to describe the geographic advance of their religion from its roots in India, across the Asian continent, and finally to Japan. In this formulation, Japan was conceived of as the last stage in the progression of Buddhism. In the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, however, Buddhist missionaries such as Bishop Uchida advocated a new eastward movement of Buddhism: this time, from Japan across the Pacific Ocean to the Americas. These pioneering Issei (or first-generation) priests and the devout Japanese Buddhist laypeople they served established a Buddhist presence in lands further east by constructing temples, transmitting Buddhist teachings and practices, and to a lesser extent, through converting non-Buddhists in the Americas. This volume explores these pioneering efforts in the contexts of late-nineteenth-and twentieth-century Japanese diasporic communities and immigration history on the one hand and the early history of Buddhism in the Americas on the other.

The eastward reorientation across the Pacific to the Americas allows us to question certain disciplinary boundaries and categories that have traditionally located Buddhism solely in Asia or defined America in Anglo-Christian terms. By examining the eastward transmission of Buddhism in conjunction with the lives of the Issei in the Americas, we will explore how Buddhism negotiated local, translocal, and transnational boundaries as well as how a multiethnic, multilingual, and multireligious vision of America emerged from the realities of transplanted Asian religious practices in Hawaii, South America, and the West Coast of the United States and Canada. In this way, we hope to build on the emerging scholarship of historians such as Thomas Tweed who have begun to retell Americas religious history with sustained attention to Asian religions in America.

The rhetoric of the American West and its opening by pioneers suggest that America faces only Europe and is centered in a New England Anglo-Protestantism every other immigrant group and religious tradition ought to assimilate into. Instead of the American West, especially for the first Japanese sojourners and settlers, the Americas should be viewed as the Pacific East. This is a perspective that is in part inspired by an emergent scholarship on American religious history at its frontiers such as that of Laurie Maffly-Kipp who focuses on the American West as part of the Pacific Rim or Americas Pacific borderlands.

Further, given Japans own colonial and imperialist ambitions, Japanese Americans could be located, in the words of Eiichiro Azuma, as between two empires: Japan and America. Yet, neither the simplistic frameworks of a Japan-centered diaspora ignoring local conditions and community formations nor an America-centered assimilationist model that reduces religious change to Americanization are adequate for understanding the place of religion in the lives of Buddhists in the Americas. The study of Issei Buddhism, thus, opens up the possibility for retelling American religious history from the perspective of those for whom Asia, rather than Europe, constituted the homeland.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper. t

t zen: The Eastward Transmission of Buddhism

zen: The Eastward Transmission of Buddhism