Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weisser, Susan Ostrov.

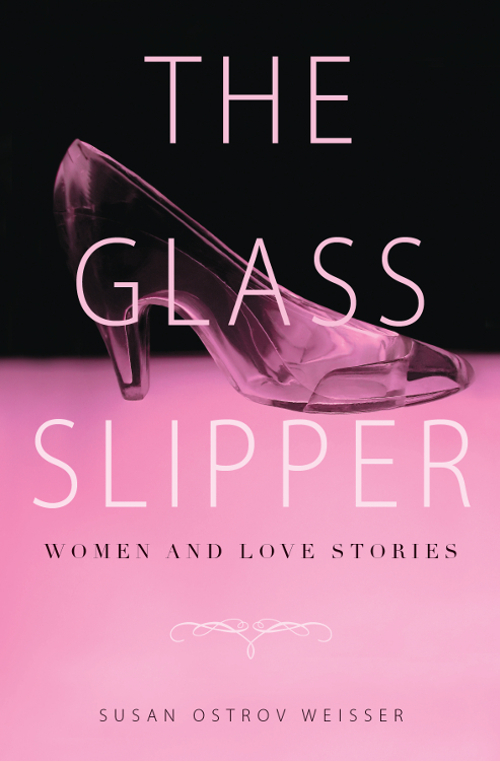

The glass slipper: women and love stories / Susan Ostrov Weisser.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780813561783 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780813561776 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780813561790 (e-book)

1. Love storiesHistory and criticism. 2. Women and literature. 3. Women in literature. 4. Love in literature. I. Title.

PN3448.L67W37 2013

809.385dc232012051437

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2013 by Susan Ostrov Weisser

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

Visit our website: http://rutgerspress.rutgers.edu

Manufactured in the United States of America

The woman in love feels endowed with a high and undeniable value.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

The original impulse to write this book came from teaching young women who face a peculiar double bind. These students consider themselves the most independent and self-determining generation of women in history, yet their expectations of love do not seem to match their real-life observations and experience of romance and marriage, and theyre not sure why. Magazine articles, self-help books, and psychology studies quoted on TV and the Internet tell them how to find the right man but seem to have helped very little.

Though most of my female students rhetorically reject the traditional feminine motive of economic security in marriage, they often worry that they wont be seen as desirable if they project independence and self-interest. The lure of being chosen by the desirable man who pursues, and the fear of not being seen as a desirable object worthy of emotional attachment, are more powerful than the threat of what they might lose through submergence in a relationship. So the old idea of a womans value as defined through her ability to attain the love of the high-status man lives on to a surprising degree. Courtship is still celebrated in movies, novels, magazines, and TV as the most special time of a womans life, as opposed to a mans.

Though Simone de Beauvoir published The Second Sex in 1949, well before the Second Wave of the womens movement in Western nations, it seems to me that many women still seek to be adored in love, perhaps more than ever. De Beauvoir claimed that women both want freedom and fear giving up the privileges of dependency. I would argue that in a society in which there are suddenly greater sexual freedoms than ever, women counter their anxiety about continuing sexual exploitation by clinging to romantic love as a kind of emotional affirmation that they are worth more than the exchange value of their bodies. The ideal and hope of being adored, protected, and given lifelong emotional security becomes insurance against the increasingly heavy demands for a kind of sexuality that is still devalued for women, though paradoxically its also encouraged and inflated. In other words, women react to the pressure to be both super-desirable (literally adore-able) and yet strong and independent by holding on to the Victorian split between the good woman, who is loved, and the hypersexual woman, who may be exploited. If theyre loved, they feel they must be good.

How do young women meet their desire to find someone to love while not compromising a strong sense of self? There arent many role models or guides for that, and so romance has become an unexamined area where many women remain squeezed between unappealing options. Heterosexual women often live with anxiety about the price paid for condemning men, which includes the good men and the desirable mates. My students resent critiques of romance as man-hating and radical or extreme and are anxious to assure me and themselves that they are not cynical or hostile... unlike feminists. Or they may define their own feminism as the power to get what they want, and vigorously endorse using their desirability as a kind of power tool. These conflicts around romantic love parallel womens similar ambivalence and anxieties surrounding beauty, youth, sexuality, and motherhood.

As the recent work of psychologists Laurie Rudman and Kim Fairchild has shown, both women and men perceive feminism and romance to be in conflict. Overwhelmingly, the postfeminist young women I encounter reject Second Wave feminists analysis of love as a power dynamic. They see romance as a semi-magical space of perfectly mutual and enduring feelings; if there is an imbalance of power, in their view, it isnt real love in the first place, and everyone will find real love eventually, so there is no problem to discuss. After all, they argue, if I need you and you need me, there is no power issue: it does not occur to them that desire, need, and dependence can assume a variety of forms that dont necessarily harmonize or equalize.

I see this topic as timely and important because romance is an area of life that informs most Western womens choices, in a way that is evolving along with modernity. While the Glass Ceiling limits female executives or members of Congress, the idea of the Glass Slipper directly affects ordinary women of all groups and classes in our culture in far greater numbers. Romantic love is intensely personal (yet also deeply social), and all the more potent for being ordinary. We have made romantic love so important in contemporary society that how we think about the promises and experiences of romance has an enormous role in shaping the direction of our lives: where we go, how we behave, who we expect to become, what we are willing to do to be loved.

Over my twenty-five years of teaching, students have shared these ideas and many of their experiences in love as well. This book is not concerned with the practice of love, however, but rather the way these experiences and beliefs are represented in the structures of storytelling. I hope to show how Victorian ideas and stories about womens sexuality, femininity, and romantic love have survived as seemingly protective elements in a more modern, feminist, sexually open society, confusing the picture for women themselves. Love stories, ranging from traditional fairy tales to the classic Jane Eyre to the reality show The Bachelor, tend to be conservative in their appeals to women, using themes and images from the Victorian age. My intent is to explain why we cling to these old stories of gender and romance, linking these to modern womens anxieties about their value in the emotional marketplace.

I am as grateful as I should be to those who helped me through the writing and editing process these last three years. First among these is Leslie Mitchner, editor extraordinaire at Rutgers University Press, whose skill is well matched by her creativity and kindness. I am grateful to the terrific staff at Rutgers University Press, especially India Cooper, my copy editor. I would also like to thank the following for their contributions, from expert suggestions and good conversation to help with information and other tasks, undertaken with a good heart: Roni Berger, Jerome Bruner, Marsha Darling, Maeghan Donohue, Diane Della Croce, Sarah Frantz, Bernard Gendron, Jessica Harris, Eric Heinemann, Dora Keller, Elayne Rapping, Sonia Jaffe Robbins, Edwin Troeber, Robyn Warhol, and Sokthan Yeng. Adelphi University supported my research with released time; I greatly appreciate the assistance of former dean Stephen Rubin. Thanks to Barnes & Noble Inc. and Maney Publishing for their kind permission to reprint previously published portions of my work. And not least, I know how fortunate I am to have a ruthless professional editor in the family: many thanks to Cybele Weisser for her patient, unpitying (and unpaid) aid when the going was rough.