SAGE Publications Ltd

1 Olivers Yard

55 City Road

London EC1Y 1SP

SAGE Publications Inc.

2455 Teller Road

Thousand Oaks, California 91320

SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd

B 1/I 1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area

Mathura Road

New Delhi 110 044

SAGE Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd

3 Church Street

#10-04 Samsung Hub

Singapore 049483

Andrew McStay 2018

First published 2018

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017957217

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-4739-7110-3

ISBN 978-1-4739-7111-0 (pbk)

Editor: Michael Ainsley

Assistant editor: John Nightingale

Production editor: Imogen Roome

Copyeditor: Aud Scriven

Proofreader: Leigh C. Smithson

Indexer: Silvia Benvenuto

Marketing manager: Lucia Sweet

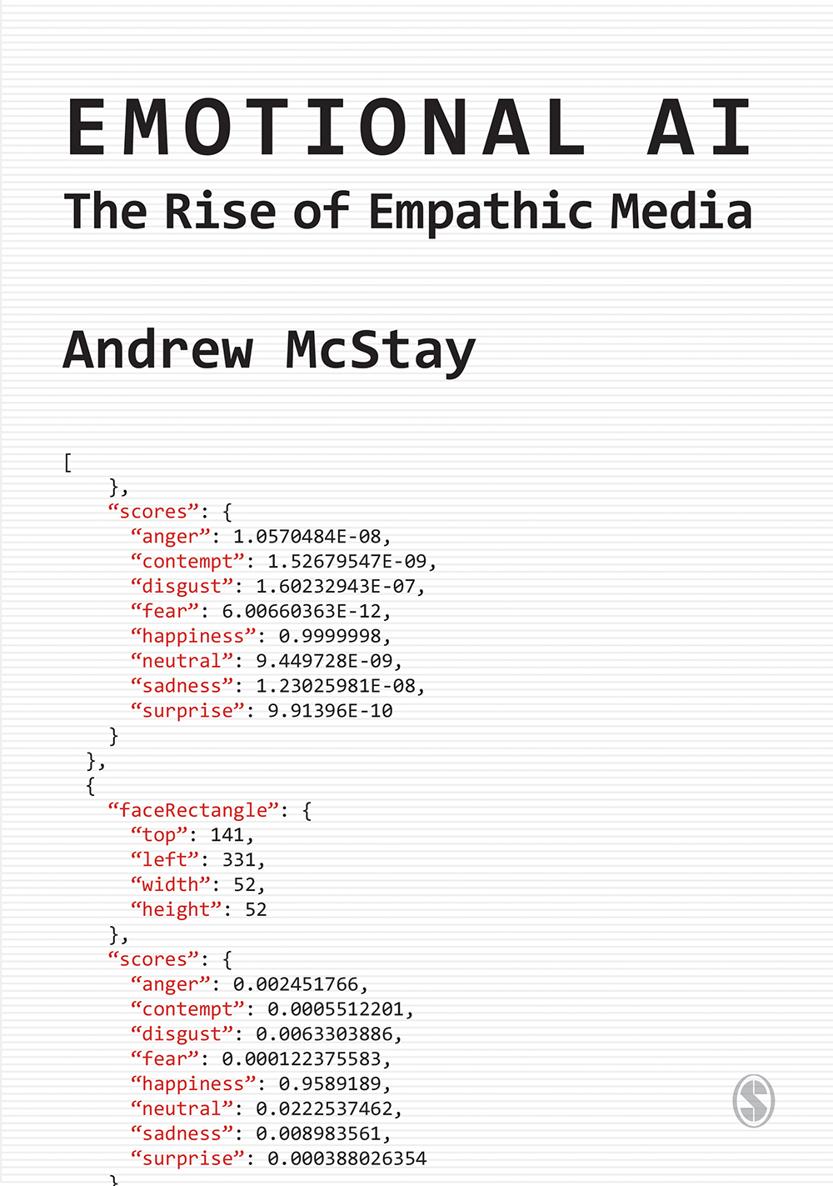

Cover design: Francis Kenney

Typeset by: C&M Digitals (P) Ltd, Chennai, India

Printed in the UK

Introducing Empathic Media

Emotions matter. They are at the core of human experience, shape our lives in the profoundest of ways and help us decide what is worthy of our attention. The idea behind this book is to explore what happens when media technologies are able to interpret feelings, emotions, moods, attention and intention in private and public places. I argue this equates to a technological form of empathy. As we will see, there are many personal and organisational drivers for using technologies to understand how individuals and groups of people feel and see things. These include making technologies easier to use, evolving services, creating new forms of entertainment, giving pleasure, finding novel modes of expression, enhancing communication, cultivating health, enabling education, improving policing, heightening surveillance, managing workplaces, understanding experience and influencing people. This is done through capturing emotions. In computer science parlance capture simply means causing data to be stored in a computer, but capture of course has another meaning: taking possession by force. This book is in many ways an account of the difference between these two understandings.

Overall I suggest that we are witnessing a growing interest in mediated emotional life and that neither the positive or negative dimensions of this have been properly explored. This situation is becoming more pressing as society generates more information about emotions, intentions and attitudes. As a minimum, there is the popularity of animojis, emojis and emoticons on social media. These facilitate non-verbal shorthand communication, but they also allow services insight into how content, brands, advertising campaigns, products and profiles make people feel. The vernacular of emoticons increasingly applies both online and offline, as we are asked for feedback about our perspectives, how we are and whats happening. The emotionalising of modern mediated life is not just about smileys, however. Rather, the sharing of updates, selfies and point-of-view content provides valuable understanding of life moments, our perspectives and individual and collective emotions.

Interest in feelings, emotions, moods, perspectives and intentions is diverse. Political organisations and brands trace how we feel about given messages, policies, candidates and brand activity through online sentiment analysis. Similarly, advertising agencies, marketers and retailers internally research what we say, post, listen to, our facial expressions, brain behaviour, heart rate and other bodily responses to gauge reactions to products, brands and adverts. Increasingly, digital assistants in the home and on our phones are progressing to understand not just what we say, but how we say it. In terms of affective media experience, virtual reality has raised the bar in unexpected ways. As well as generating emotional responses that can be measured, this also tells analysts a great deal about what captures our attention. Augmented reality promises something similar, albeit in public and commercial spaces. Wearables attached to our bodies track all sorts of biofeedback to understand emotions and how we feel over short and extended periods of time. As we will see, this potential is being applied in novel, surprising and perhaps alarming ways. Indeed, some of us even insert technologies that feel into our bodies to enhance our sex life. At a macro-level, cities are registering the emotional lives of inhabitants and visitors. This book assesses all of these phenomena, and more.

I call for critical attention and caution in the rollout of these technologies, but I should state upfront that I do not think there is anything innately wrong with technologies that detect, learn and interact with emotions. Rather, the practice of reading and detecting emotions is a step forward in improving how we interact with machines and how they respond to us. For example, as will be explored, games are enhanced through use of biofeedback and information about how we feel. The issue is not the premise of using data about emotions to interact with technology, but the nature of engagement. In short, while all might enjoy and appreciate the focus on experience (user, consumer, patient and citizen), it is paramount that people have meaningful choice and control over the capturing of information about emotions and their bodies.