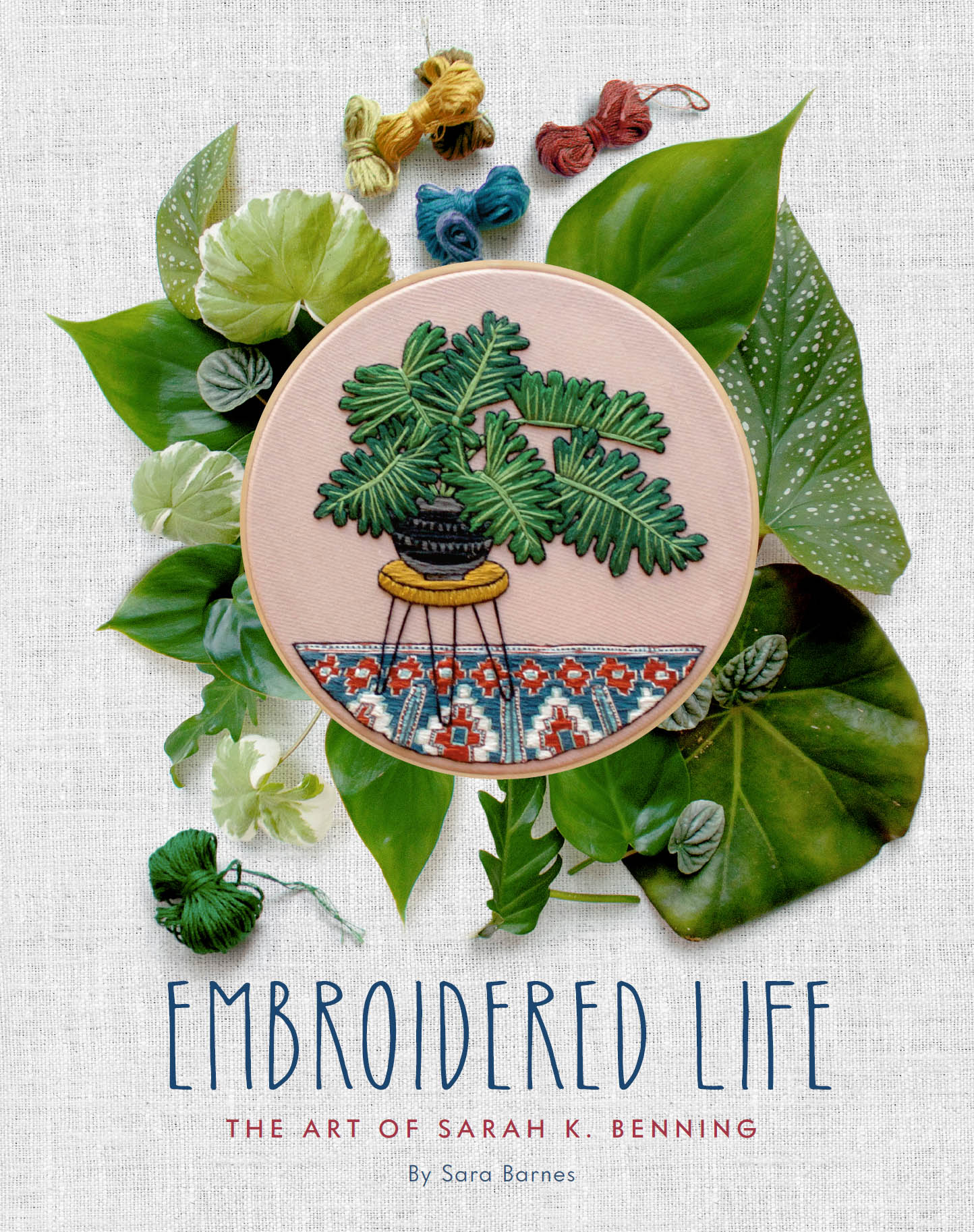

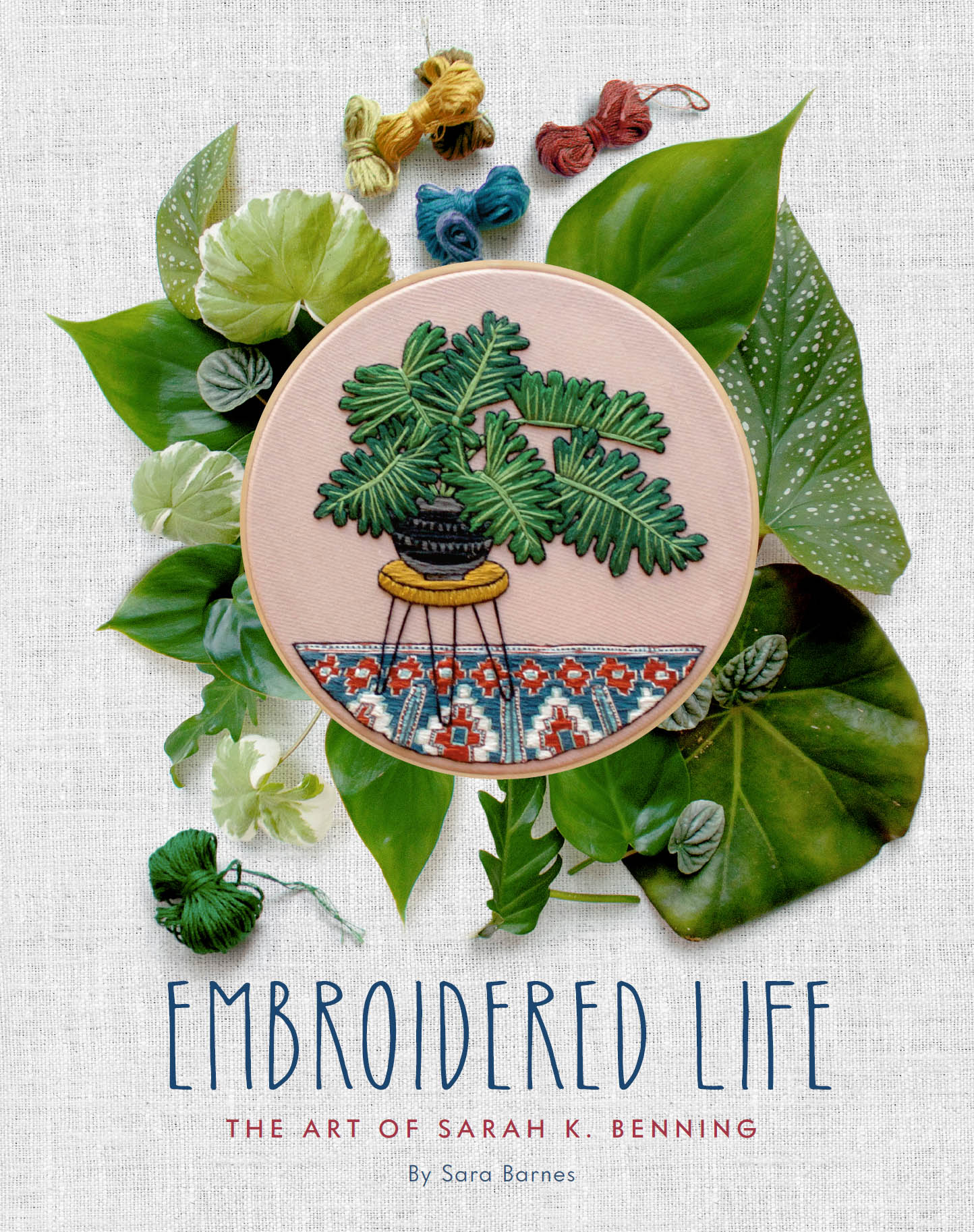

Text copyright 2019 by Sara Barnes.

Photography copyright 2019 by Sarah K. Benning.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-7367-2 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-7346-7 (hardcover)

Design by Kayla Ferriera.

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

CONTENTS

When the subject of embroidery is brought up in casual conversation, one common refrain emerges: Oh, my grandma does that. While that may be true, this dismissive sentiment belittles the art of embroidery (not to mention the awesomeness of grandmas).

Embroidery has been around for a very long time and stays alive, in part, by being passed down from generation to generation. Traditionally, we humans have stuck close to home and carried on the customs of our ancestors. Its how our personal histories stay aliverecipes get passed down and stories of kooky relatives become legends (or cautionary tales). So if youve tried embroidery, your first encounter was likely through an immediate family member, relative, or friend. Depending on whom youve learned your techniques from, it might seem like thats the only way to stitch. But, embroidery is much bigger than our small communities or even countries. Embroidery has touched every part of the world.

It would be impossible to describe all of the embroidery approaches from different places around the globe in just a few pages. Doing so would make this book a giant tome. Instead, we can look to a couple of embroideries and techniques to illuminate some of the defining works of the craft. These pieces have shaped contemporary embroidery in a couple of important ways: firstly, by demonstrating how the craft can be a celebration of color, texture, and material; and secondly, by using thread to illustrate a story.

Embroidery existed in ancient worlds. Although much of it is gone, a few pieces have survived to give us clues as to how the craft was used so long ago. One early form of embroidery was used in clothing. For common folks, this included the mending of garments. But for royalty, the stitching had another purposeit was a way to show status and display wealth through adornment. With just one look, it became clear that someone wearing an embroidered garment was held in high regard.

The tomb of Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun gives us some clues to how this would have looked. When it was unearthed in 1922, archaeologists found some of the oldest surviving embroideries inside. Tutankhamun was buried during the fourteenth century BCE, and some of the stitched garments had been reduced to dust. But the array of surviving textiles represented an incredible cache of embroidery. Dr. Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood and her students at the Stitching Textile Research Centre, part of the National Museum of Ethnology in the Netherlands, began cataloging the collection in the mid-1990s and found more than one hundred loincloths, a dozen tunics, two dozen gloves and shawls, various head coverings, and socks (designed to be worn with sandals).

We often think of embroidery as stitching with only thread, but it can also incorporate glass, metal, seeds, and beads. Tutankhamuns wardrobe featured beaded aprons and tunicssome so heavy with baubles that its hard to believe the young king (who died when he was about eighteen) wore them on a regular basis. Other decorative needleworkincluding the appliqu techniquewas used to embellish two pairs of wings (believed to be worn to imitate winged Egyptian gods), skullcaps, and more.

These Egyptian textiles demonstrate a decorative approach to embroidery, where the imagery and designs arent necessarily telling a story or adding to the function of the design. Rather, they are enjoyed for their aesthetic qualities.

The eleventh century Bayeux Embroidery, on the other hand, exemplifies the illustrative, storytelling potential of embroidery. You might know this piece by its other name, the Bayeux Tapestrybut technically its not a tapestry but a detailed work of embroidery. Measuring more than 230 feet long and nearly 20 inches tall, the piece illustrates 72 scenes that provide an account of the Norman conquest of England in 1066. In addition to events pictured, there are medieval Latin inscriptions, called tituli, that narrate each scene.

Completed by a professional embroidery workshop, many hands stitched this journal in thread. It was sewn on nine linen panels and features six sections that use the crewel work approacha form of embroidery using worsted yarn in two twisted strandsin muted shades of greens and blues, as well as terracotta, buff, red, and yellow. A combination of stitches helped complete this massive undertaking; the couch stitch helped to fill the solid areas, while the outline and stem stitch were employed for the contour lines and text.

Everything in Bayeux Embroidery is the work of stitching, from the figures to the animals (220 birds and 41 griffins) to the decorative borders that line the text. This eleventh-century piece demonstrates that a needle can be used in the same way as a pencil or a paintbrush to tell a story that reflects events real or imagined.

The popularity of embroidery has waxed and waned over time, but it experienced a resurgence in 2009. Rozsika Parker, in her book The Subversive Stitch, finds that the boost in embroidered activities often corresponds with financial recessionsfrom which the world was still recovering in 2009citing 1984 as another example of the phenomenon. When the economy tanks, the desire for homecrafts rises; embroidery provides hours (upon hours) of entertainment and allows you to upcycle used items by adding decorative embellishments, thus breathing new life into them. The renewed interest in the craft after our recent global recession helped set the stage for Sarah K. Benning to start her practice and eventually her business.

Sarah is not a typical embroiderer. Largely self-taught, she has abandoned traditional rules and techniques. I never did an embroidery pattern, she explains, and I abandoned the stitch encyclopedia I bought pretty quickly. It felt stuffy and difficult and frustrating. And datedinstantly dated. Affording herself this freedom from the rules of the craft allowed her to explore it from the perspective of an artist. I decided that I was more interested in using thread as any kind of medium. Her first pieces werent even on fabricthey were on paper. In thinking of her practice in this way, she subverts traditional notions of embroiderythey are not grandmas completing a counted cross stitch (although lets applaud the ones that do). In some ways, she views herself as an outsider to the field. I dont always think of myself as fitting into an embroidery-specific narrative, she asserts, because Ive always approached it as image making that happens to be in the technique of embroidery. I think of it as illustration practice that happens to be in thread. Sarahs radical decision to bypass typical techniques helped to usher in an era of contemporary embroidery. Even now, most of her work is comprised of a single type of stitch.

Next page