Table of Contents

2003 by Rockport Publishers, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the copyright owners. All images in this book have been reproduced with the knowledge and prior consent of the artists concerned, and no responsibility is accepted by producer, publisher, or printer for any infringement of copyright or otherwise, arising from the contents of this publication. Every effort has been made to ensure that credits accurately comply with information supplied.

First published in the United States

of America by:

Rockport Publishers, Inc.

100 Cummings Center

Suite 406-L

Beverly, Massachusetts 01915-6101

Telephone: (978) 282-9590

Fax: (978) 283-2742

www.rockpub.com

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lidwell, William.

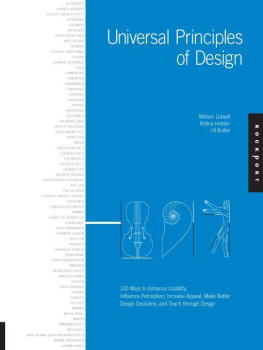

Universal principles of design : a cross-disciplinary reference /

William Lidwell, Kritina Holden, and

Jill Butler. p. cm.

ISBN 1-59253-007-9 (paper over board)

1. Design-Dictionaries. I. Holden, Kritina. II. Butler, Jill. III. Title.

NK1165.L53 2003

745.403dc21 2003009384 CIP

ISBN-13: 978-1-59253-007-6 ISBN-10: 1-59253-007-9

20 19

Design: Collaborated, Inc. James Evelock Tony Leone

Printed in Singapore

For our dads...

John C. Butler

Larry W. Lidwell

Introduction

Not long ago, designers were eclectic generalists. They studied art, science, and religion in order to understand the basic workings of nature, and then applied what they learned to solve the problems of the day. Over time, the quantity and complexity of accumulated knowledge led to increased specialization among designers, and breadth of knowledge was increasingly traded for depth of knowledge. This trend continues today. As designers become more specialized, awareness of advances and discoveries in other areas of specialization diminishes. This is inevitable and unfortunate, since much can be learned from progress in other design disciplines.

Convenient access to cross-disciplinary design knowledge has not previously been available. A designer interested in learning about other areas of specialization would have to study texts from many different design disciplines. Determining which texts in each discipline are worthy of study would be the first challenge, deciphering the specialized terminology of the texts the second, and enduring the depth of detail the third. The effort is significant, and rarely expended beyond brief excursions into unfamiliar areas to research specific problems. The goal of this book is to assist designers with these challenges, and reduce the effort required to learn about the key principles of design across disciplines.

The concepts in this book, broadly referred to as principles, consist of laws, guidelines, human biases, and general design considerations. The principles were selected from a variety of design disciplines based on several factors, including utility, degree of misuse or misunderstanding, and strength of supporting evidence. The selection of 100 concepts should not be interpreted to mean that there are only 100 relevant principles of designthere are obviously many more.

The book is organized alphabetically so that principles can be easily and quickly referenced by name. For those interested in addressing a specific problem of design, the principles have also been indexed by questions commonly confronting designers (see previous page). Each principle is presented in a two-page format. The left-hand page contains a succinct definition, a full description of the principle, examples of its use, and guidelines for use. Side notes appear to the right of the text, and provide elaborations and references. The right-hand page contains visual examples and related graphics to support a deeper understanding of the principle.

Sound design is not only within the reach of a small set of uniquely talented individuals, but can be achieved by virtually all designers. The use of well-established design principles increases the probability that a design will be successful. Use Universal Principles of Design as a resource to increase your cross-disciplinary knowledge and understanding of design, promote brainstorming and idea generation for design problems, and refresh your memory of design principles that are infrequently applied. Finally, use it as a means of checking the quality of your design process and product. A paraphrase of William Strunks famous admonition makes the point nicely:

The best designers sometimes disregard the principles of design. When they do so, however, there is usually some compensating merit attained at the cost of the violation. Unless you are certain of doing as well, it is best to abide by the principles.

William Lidwell

Kritina Holden

Jill Butler

80/20 Rule

A high percentage of effects in any large system are caused by a low percentage of variables.

The 80/20 rule asserts that approximately 80 percent of the effects generated by any large system are caused by 20 percent of the variables in that system. The 80/20 rule is observed in all large systems, including those in economics, management, user-interface design, quality control, and engineering, to name a few. The specific percentages are not important, as measures of actual systems indicate that the proportion varies between 10 percent and 30 percent. The universality of the 80/20 rule suggests a link to normally distributed systems, which limits its application to variables that are influenced by many small and unrelated effectse.g., systems that are used by large numbers of people in a variety of ways. A few examples of the 80/20 rule include:

percent of a products usage involves percent of its features.

percent of a towns traffic is on percent of its roads.

percent of a companys revenue comes from percent of its products.

percent of innovation comes from percent of the people.

percent of progress comes from percent of the effort.

percent of errors are caused by percent of the components.

The 80/20 rule is useful for focusing resources and, in turn, realizing greater efficiencies in design. For example, if the critical 20 percent of a products features are used 80 percent of the time, design and testing resources should focus primarily on those features. The remaining 80 percent of the features should be reevaluated to verify their value in the design. Similarly, when redesigning systems to make them more efficient, focusing on aspects of the system beyond the critical 20 percent quickly yields diminishing returns; improvements beyond the critical 20 percent will result in less substantial gains that are often offset by the introduction of errors or new problems into the system.

All elements in a design are not created equal. Use the 80/20 rule to assess the value of elements, target areas for redesign and optimization, and focus resources efficiently. Noncritical functions that are part of the less-important 80 percent should be minimized or even removed altogether from the design. When time and resources are limited, resist efforts to correct and optimize designs beyond the critical 20 percent, as such efforts yield diminishing returns. Generally, limit the application of the 80/20 rule to variables in a system that are influenced by many small and unrelated effects.

See also Cost-Benefit, Form Follows Function, Highlighting, and Normal Distribution.