THE POCKET

UNIVERSAL

PRINCIPLES OF DESIGN

William Lidwell Kritina Holden Jill Butler

Contents

Author Favorites

Our Most Used Principles of Design

WILLIAM LIDWELL

002 80/20 Rule

006 Affordance

026 Confirmation Bias

038 Desire Line

052 Flexibility Trade-Offs

065 Hanlons Razor

078 KISS

114 Root Cause

122 Selection Bias

132 Sunk Cost Effect

KRITINA HOLDEN

019 Chunking

042 Errors

050 Fitts Law

054 Forgiveness

059 Garbage In-Garbage Out

066 Hicks Law

086 Mapping

100 Performance vs. Preference

111 Recognition Over Recall

130 Storytelling

JILL BUTLER

011 Area Alignment

014 Back-of-the-Dresser

040 Dunning-Kruger Effect

051 Five Hat Racks

053 Flow

069 Highlighting

070 Horror Vacui

082 Legibility

088 Mental Model

126 Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Less and More.

Dieter Rams

3D Projection

A tendency to see things as three-dimensional when certain visual cues are present.

People see two-dimensional things as three-dimensional when certain visual cues are present.

When items are relatively larger, lower, less dense in pattern, lighter, clearer, or in front of other objects, they are perceived to be closer.

When items are relatively smaller, higher, denser in pattern, bluer, blurrier, or behind other objects, they are perceived to be farther away.

Consider 3D projection in the depiction of three-dimensional elements and environments. Strongest depth effects are achieved when the visual cues are used in combination; therefore, use as many of the cues as possible to achieve the strongest effect.

See Also Common Fate Figure-Ground Law of Prgnanz Top-Down Lighting Bias Visuospatial Resonance

Applying 3D projection in sidewalk art can create stunning three-dimensional effects on two-dimensional surfaces.

80/20 Rule

A high percentage of effects in any large system is caused by a low percentage of variables.

Proposed by the economist Vilfredo Pareto, who observed that 20 percent of the Italian people possessed 80 percent of the wealth.

Applying the 80/20 rule means identifying and focusing resources on the critical 20 percent. Focusing on aspects of a design beyond the critical 20 percent yields diminishing returns.

For example, 80 percent of a products usage involves 20 percent of its features; 80 percent of a products bugs are caused by 20 percent of its components.

Use the 80/20 rule to assess the relative value of elements, target areas of redesign and optimization, and focus resources in an efficient manner. Note that 80/20 is just an estimate. The actual percentages can be more or less (e.g., 70/30, 90/10).

See Also Cost-Benefit Feature Creep Hanlons Razor Normal Distribution Ockhams Razor

In 1979, most believed that a music player with no radio, no speakers, no recording function, and small headphones was doomed to fail. Sony proved them wrong. The Walkman possessed the critical 20 percent of what people wantedportability and tape playbackenabling the rest to be cut.

Abbe

Measure things as close to their action as possible.

Proposed by the German physicist Ernst Abbe.

Abbe errors are angular errors that increase with distance. For example, wobble from a bent axle increases with the length of the axle. The Abbe principle prevents this type of error.

The Abbe principle states that the best measurements are achieved when taken as close to the action as possible. For example, placing a temperature sensor near a heat source will result in more accurate measurements than a sensor placed farther away.

The principle also has implications for the design of mechanisms. Actuators and bearings should be placed as close to lines of action as possible.

Consider the Abbe principle in measurement, and the design of mechanical systems and structures. Locate measurement devices and components as close to the areas of action as possible.

See Also Error Redundancy Saint-Venants Principle

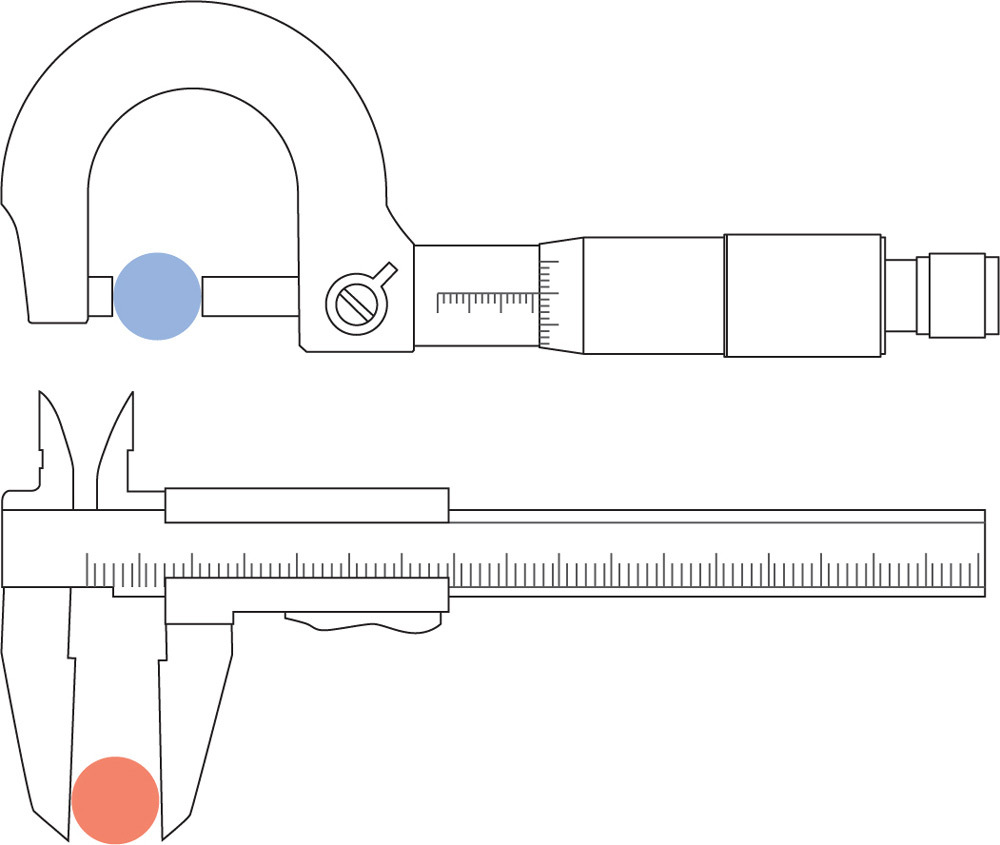

A caliper that measures in its line of action (top) is more accurate than a caliper that measures away from its line of action (bottom).

Accessibility

Things should be designed to be usable, without modification, by as many people as possible.

Historically, accessibility in design focused on accommodating people with disabilities.

Modern practice accepts that most accommodations can be designed to benefit everyone.

Make things perceptible by everyone. For example, position controls and information so that seated and standing people can perceive them.

Make things usable by everyone. For example, minimize repetitive actions and the need for sustained physical effort.

Make things learnable by everyone. For example, use redundant coding methods (e.g., textual, iconic, and tactile) on controls and signage.

Make the consequences of errors non-catastrophic, and reversible whenever possible.

See Also Affordance Forgiveness Normal Distribution

Inventor Dean Kamen demonstrating the iBot, a Transformer-like wheelchair that makes a world designed for those who can stand and walk accessible to wheelchair users.

Aesthetic-Usability Effect

Aesthetic things are perceived to be easier to use than ugly things.

Aesthetic things are often subjectively rated as easier to use, even when no usability advantage can be objectively measured.

Aesthetic things are more effective at fostering positive attitudes than ugly things, making people more tolerant when problems are encountered.

Aesthetic things are more likely to be tried, accepted, displayed, and repeatedly used than ugly things.

Aspire to create aesthetically pleasing designs. It is more than ornamentationit is an investment in user acceptance, forgiveness, and satisfaction.

See Also Attractiveness Bias Cognitive Dissonance Form Follows Function IKEA Effect

People display the HomeHero extinguisher on counters due to its striking aesthetic, making it more accessible in emergencies.

Affordance

The physical characteristics of a thing influence its function and use.

The form of a thing makes it better suited for some functions than others. For example, wheels afford rolling, and negatively afford being stationary.

The form of a thing makes it better suited for some interactions than others. For example, buttons afford pushing, and negatively afford pulling.